Divulgation

Divulgation finance sociale et investissement responsable Gouvernance normes de droit Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Structures juridiques

Normes ESG: 2024 sera une année charnière

Ivan Tchotourian 22 novembre 2023 Ivan Tchotourian

Un beau numéro spécial dans le journal Les affaires.com : « Normes ESG: 2024 sera une année charnière » (novembre 2023).

Vous pouvez lire ci-dessous l’édito de Mme Marine Thomas (pour y accéder, cliquez ici) :

Bien sûr, la notion de bonnes pratiques environnementales, sociales et de gouvernance n’a rien de nouveau, ce sont des facteurs mesurés depuis une quinzaine d’années. La différence, c’est que jusque-là, tout le monde y allait à son gré dans la divulgation extrafinancière, les méthodes de calcul et les cadres de référence variant énormément. Les entreprises faisaient alors soit une évaluation de bonne foi, soit une «comptabilité créative» de leur bilan en matière de responsabilité sociale pour bien paraître.

Ça, c’était avant. L’harmonisation des normes du Conseil des normes internationales d’information sur la durabilité (ISSB) va mettre tout le monde au pas, du moins sur un pied d’égalité. Il sera désormais pas mal plus difficile de cacher une piètre performance en matière de développement durable.

Si vous pensez que vous avez le temps d’ici à ce que ce changement survienne, détrompez-vous. L’entrée en vigueur est dans deux mois et cela va créer une accélération considérable sur le marché.

Les grandes entreprises qui vont devoir exposer en plein jour les émissions de gaz à effet de serre qu’elles produisent sur l’ensemble de leur chaîne de valeur ne comptent pas porter ce fardeau seules. Elles vont se tourner vers celles qui les approvisionnent, généralement des PME, pour les aider à alléger leur propre bilan. La proportion de grands donneurs d’ordre avec des exigences ESG envers leurs fournisseurs devrait grimper à 92% d’ici 2024, nous révèle le rapport «L’ESG dans votre entreprise: un avantage pour décrocher de gros contrats» publié par la BDC au printemps. Un fait qui est encore largement sous le radar de PME et qui va leur tomber dessus comme un coup de massue le moment venu.

Pour les dirigeants qui pensent encore qu’agir en faveur des changements climatiques ne concerne que les woke, le réveil risque de faire mal. Qu’on se le dise: il ne s’agit plus d’une question de valeurs ou d’appartenance politique. Il s’agit ici d’affaires, tout simplement. Toutes les entreprises seront touchées, ne serait-ce que par leur financement.

Vous trouvez les taux d’intérêt élevés? Imaginez payer davantage, car votre entreprise n’est pas assez verte ou inclusive! En Europe, c’est déjà le cas. Ici, les institutions financières s’y préparent activement. Après tout, l’investissement, c’est avant tout de la gestion de risques, et les risques climatiques pèsent lourdement dans la pérennité de nombreuses entreprises. En outre, les banques auront elles aussi intérêt à montrer «patte verte» en prêtant à des entreprises ayant une plus faible empreinte pour leur propre bilan.

La bonne nouvelle, c’est qu’un nombre toujours plus important de PME prennent conscience des risques liés au climat et passent à l’action en faveur de la transition, comme nous le révèle le Baromètre de la transition des entreprises 2023 de Québec Net Positif, que nous vous offrons en exclusivité.

Pour ces PME, les changements à venir peuvent présenter de sérieux atouts. La recherche d’un approvisionnement durable et d’une réduction des distances de transport va signifier un nouvel intérêt pour des entreprises locales ayant su se positionner. Toute longueur d’avance prise maintenant sera difficile à rattraper par la concurrence qui n’aura pas su se transformer à temps.

Même si tous ces acronymes — ESG, RSE, GES, EDI… — peuvent donner le tournis, vous n’avez plus le choix de les connaître, et surtout d’en tenir compte. Alors que les entreprises commencent les budgets et la planification de 2024, elles ont tout intérêt, si ce n’est pas déjà fait, à mettre la préparation d’un plan en matière de développement durable tout en haut de leur liste de leurs priorités.

Tenez-le-vous pour dit: prêts, pas prêts, les nouvelles normes ESG arrivent et elles vont tout bouleverser!

À la prochaine…

actualités canadiennes Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement

Divulgation ESG : les entreprises canadiennes font mieux

Ivan Tchotourian 14 septembre 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

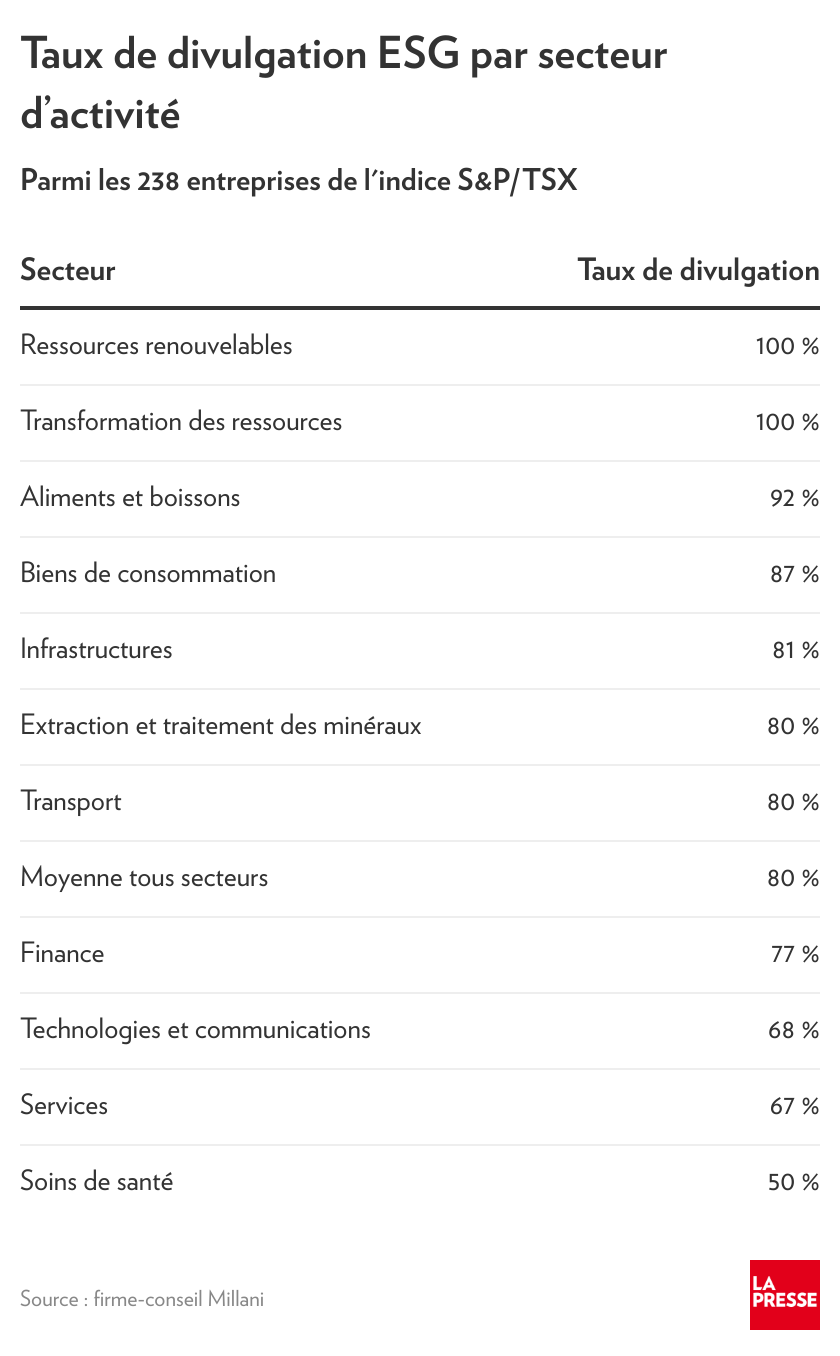

Dans La presse.ca, le journaliste Martin Vallières diffuse les enseignements du dernier rapport Milani montrant que les grandes entreprises canadiennes améliorent leur diffusion des critères ESG. Bonne nouvelle pour la RSE !

Extrait :

« Notre recherche révèle que 80 % des entreprises de l’indice S&P/TSX publient maintenant un rapport ESG, ce qui est mieux que le taux de 71 % mesuré un an plus tôt, mais encore inférieur au 92 % parmi les entreprises de l’indice S&P 500 », lit-on dans le rapport de la firme Millani.

En parallèle, constate Millani, « bien que les rapports ESG soient de plus en plus nombreux, les investisseurs cherchent désormais plus qu’un rapport ».

« Les investisseurs expriment leur désir de comprendre plus profondément les impacts de ces sujets ESG : comment sont-ils gérés, quels sont les indicateurs de performance qui sont suivis et comment évoluent-ils ? Quelle est la capacité d’une entreprise à s’adapter aux risques et à atténuer les impacts négatifs futurs ? »

De plus, signale le rapport de Millani, « les entreprises qui se démarquent dans la valeur stratégique des enjeux en ESG incorporent des mesures de performance en ce sens dans la rémunération du conseil d’administration et de la direction ».

À la prochaine…

Divulgation finance sociale et investissement responsable Gouvernance Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Fonds de pension hollandais : fronde contre le greenwashing

Ivan Tchotourian 23 novembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

IPE Magazine de novembre 2020 publie un article de Tjibbe Hoekstra initulé : « Survey: Dutch pension funds accuse asset managers of greenwashing » (16 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Some asset managers do not invest as responsibly as they claim, a number of Dutch pension funds have said.

In a survey among 31 Dutch pension funds carried out by Dutch pensions publication Pensioen Pro, six in 10 Dutch pension funds agreed with the statement that some asset managers engage in greenwashing.

None of the participating pension funds, with combined assets under management worth €1.2trn, disagreed with the statement that greenwashing is a problem.

An important reason asset managers are being given the chance to engage in greenwashing is a lack of commonly agreed environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) standards, many pension funds believed.

Some 56% of respondents even saw the absence of a common ESG definition as a threat to responsible investing, the survey found.

Responsible investing is a rising trend in the Dutch pension sector, with 87% of the surveyed funds now having their own sustainable investment policy. The remaining 13% have outsourced this to their fiduciary manager.

None of the surveyed funds said they have no dedicated policy for responsible investing.

À la prochaine…

actualités canadiennes Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Normes d'encadrement Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

CFA Institute : document de consultation

Ivan Tchotourian 26 octobre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

CFA Institute a proposé des standards en matière de divulgation des critères ESG dans les produits financiers : « Consulter Paper on the Development of the CFA Institute – ESG Disclosure Standards For Investments Products » (août 2020).

- Pour un article de presse : ici

Petit extrait :

- Disclosure Requirements Many of the Standard’s requirements will be related to disclosures. Disclosure requirements are a key way to provide transparency and comparability for investors. A disclosure requirement is simply a means of ensuring that asset managers communicate certain information to investors. There are different ways that disclosures might be required, both in terms of scope and method. Therefore, it is necessary to establish principles to ensure the disclosure requirements meet the purpose of the Standard. We propose the following design principles:

- Disclosure requirements should focus on relevant, useful information. Disclosures must provide information that will help investors better understand investment products, make comparisons, and choose among alternatives. • Disclosure requirements should focus primarily on ESG-related features. Because the goal of the Standard is to enable greater transparency and comparability of investment products with ESG-related features, the Standard’s disclosure requirements should focus on these features. Focusing the disclosure requirements on ESG-related features also avoids adding unnecessarily to an asset manager’s disclosure burden.

- Disclosure requirements should allow asset managers the flexibility to make the required disclosure in the clearest possible manner given the nature of the product. Disclosure requirements can easily be reformulated as questions. There are two types of questions—open-ended and closed-ended. Open-ended questions ask who, what, why, where, when, or how. Closed-ended questions require answers in a specific form—either yes/no or selected from a predefined list. The open-ended disclosure requirement format provides the flexibility needed for the Standard to be relevant on a global scale and to pertain to all types of investment products with ESG-related features. The open-ended nature of the disclosure requirements, however, must be balanced to a certain degree with a standardization of responses for the sake of comparison by investors. The forthcoming Exposure Draft will include examples of openended and standardized disclosures.

- The disclosure requirements should aim to elicit a moderate level of detail. An investment product’s disclosures should accurately and adequately represent the policies and procedures that govern the design and implementation of the investment product. The Standard’s disclosure requirements can be thought of as a step between a database search and a due diligence conversation. The disclosures will provide more detail than can be standardized and presented in a database but less detail than the information one can obtain through a full due diligence process.

- The disclosure requirements should prioritize content over format. The disclosure requirements will focus on what information is disclosed rather than how it is disclosed. The Standard will provide a certain degree of flexibility in the format for information presentation. Providing latitude in the format is intended to reduce an asset manager’s disclosure burden and allow for harmonization with disclosures required by regulatory bodies and other standards. The Exposure Draft will offer examples of presentation formats. • Disclosure requirements should be categorized as “general” or “feature-specific”. The Standard will have both general and feature-specific disclosure requirements. General disclosure requirements will apply to all investment products that seek to comply with the Standard. Feature-specific disclosure requirements will apply only to investment products that have a specific ESG-related feature.

- The Standard should include disclosure recommendations in addition to requirements. We anticipate that in addition to the Standard’s required disclosures, the Standard will have recommended disclosures as well. Required disclosures represent the minimum information that must be disclosed in order to comply with the Standard. Recommended disclosures provide additional information that investors may find helpful in their decision making. Recommended disclosures are encouraged but not mandatory.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement normes de droit normes de marché Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Approche juridique sur la transparence ESG

Ivan Tchotourian 3 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Excellente lecture ce matin de ce billet du Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance : « Legal Liability for ESG Disclosures » (de Connor Kuratek, Joseph A. Hall et Betty M. Huber, 3 août 2020). Dans cette publication, vous trouverez non seulement une belle synthèse des référentiels actuels, mais aussi une réflexion sur les conséquences attachées à la mauvaise divulgation d »information.

Extrait :

3. Legal Liability Considerations

Notwithstanding the SEC’s position that it will not—at this time—mandate additional climate or ESG disclosure, companies must still be mindful of the potential legal risks and litigation costs that may be associated with making these disclosures voluntarily. Although the federal securities laws generally do not require the disclosure of ESG data except in limited instances, potential liability may arise from making ESG-related disclosures that are materially misleading or false. In addition, the anti-fraud provisions of the federal securities laws apply not only to SEC filings, but also extend to less formal communications such as citizenship reports, press releases and websites. Lastly, in addition to potential liability stemming from federal securities laws, potential liability could arise from other statutes and regulations, such as federal and state consumer protection laws.

A. Federal Securities Laws

When they arise, claims relating to a company’s ESG disclosure are generally brought under Section 11 of the Securities Act of 1933, which covers material misstatements and omissions in securities offering documents, and under Section 10(b) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and rule 10b-5, the principal anti-fraud provisions. To date, claims brought under these two provisions have been largely unsuccessful. Cases that have survived the motion to dismiss include statements relating to cybersecurity (which many commentators view as falling under the “S” or “G” of ESG), an oil company’s safety measures, mine safety and internal financial integrity controls found in the company’s sustainability report, website, SEC filings and/or investor presentations.

Interestingly, courts have also found in favor of plaintiffs alleging rule 10b-5 violations for statements made in a company’s code of conduct. Complaints, many of which have been brought in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, have included allegations that a company’s code of conduct falsely represented company standards or that public comments made by the company about the code misleadingly publicized the quality of ethical controls. In some circumstances, courts found that statements about or within such codes were more than merely aspirational and did not constitute inactionable puffery, including when viewed in context rather than in isolation. In late March 2020, for example, a company settled a securities class action for $240 million alleging that statements in its code of conduct and code of ethics were false or misleading. The facts of this case were unusual, but it is likely that securities plaintiffs will seek to leverage rulings from the court in that class action to pursue other cases involving code of conducts or ethics. It remains to be seen whether any of these code of conduct case holdings may in the future be extended to apply to cases alleging 10b-5 violations for statements made in a company’s ESG reports.

B. State Consumer Protection Laws

Claims under U.S. state consumer protection laws have been of limited success. Nevertheless, many cases have been appealed which has resulted in additional litigation costs in circumstances where these costs were already significant even when not appealed. Recent claims that were appealed, even if ultimately failed, and which survived the motion to dismiss stage, include claims brought under California’s consumer protection laws alleging that human right commitments on a company website imposed on such company a duty to disclose on its labels that it or its supply chain could be employing child and/or forced labor. Cases have also been dismissed for lack of causal connection between alleged violation and economic injury including a claim under California, Florida and Texas consumer protection statutes alleging that the operator of several theme parks failed to disclose material facts about its treatment of orcas. The case was appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, but was dismissed for failure to show a causal connection between the alleged violation and the plaintiffs’ economic injury.

Overall, successful litigation relating to ESG disclosures is still very much a rare occurrence. However, this does not mean that companies are therefore insulated from litigation risk. Although perhaps not ultimately successful, merely having a claim initiated against a company can have serious reputational damage and may cause a company to incur significant litigation and public relations costs. The next section outlines three key takeaways and related best practices aimed to reduce such risks.

C. Practical Recommendations

Although the above makes clear that ESG litigation to date is often unsuccessful, companies should still be wary of the significant impacts of such litigation. The following outlines some key takeaways and best practices for companies seeking to continue ESG disclosure while simultaneously limiting litigation risk.

Key Takeaway 1: Disclaimers are Critical

As more and more companies publish reports on ESG performance, like disclaimers on forward-looking statements in SEC filings, companies are beginning to include disclaimers in their ESG reports, which disclaimers may or may not provide protection against potential litigation risks. In many cases, the language found in ESG reports will mirror language in SEC filings, though some companies have begun to tailor them specifically to the content of their ESG reports.

From our limited survey of companies across four industries that receive significant pressure to publish such reports—Banking, Chemicals, Oil & Gas and Utilities & Power—the following preliminary conclusions were drawn:

- All companies surveyed across all sectors have some type of “forward-looking statement” disclaimer in their SEC filings; however, these were generic disclaimers that were not tailored to ESG-specific facts and topics or relating to items discussed in their ESG reports.

- Most companies had some sort of disclaimer in their Sustainability Report, although some were lacking one altogether. Very few companies had disclaimers that were tailored to the specific facts and topics discussed in their ESG reports:

- In the Oil & Gas industry, one company surveyed had a tailored ESG disclaimer in its ESG Report; all others had either the same disclaimer as in SEC filings or a shortened version that was generally very broad.

- In the Banking industry, two companies lacked disclaimers altogether, but the rest had either their SEC disclaimer or a shortened version.

- In the Utilities & Power industry, one company had no disclaimer, but the rest had general disclaimers.

- In the Chemicals industry, three companies had no disclaimer in their reports, but the rest had shortened general disclaimers.

- There seems to be a disconnect between the disclaimers being used in SEC filings and those found in ESG In particular, ESG disclaimers are generally shorter and will often reference more detailed disclaimers found in SEC filings.

Best Practices: When drafting ESG disclaimers, companies should:

- Draft ESG disclaimers carefully. ESG disclaimers should be drafted in a way that explicitly covers ESG data so as to reduce the risk of litigation.

- State that ESG data is non-GAAP. ESG data is usually non-GAAP and non-audited; this should be made clear in any ESG Disclaimer.

- Have consistent disclaimers. Although disclaimers in SEC filings appear to be more detailed, disclaimers across all company documents that reference ESG data should specifically address these issues. As more companies start incorporating ESG into their proxies and other SEC filings, it is important that all language follows through.

Key Takeaway 2: ESG Reporting Can Pose Risks to a Company

This article highlighted the clear risks associated with inattentive ESG disclosure: potential litigation; bad publicity; and significant costs, among other things.

Best Practices: Companies should ensure statements in ESG reports are supported by fact or data and should limit overly aspirational statements. Representations made in ESG Reports may become actionable, so companies should disclose only what is accurate and relevant to the company.

Striking the right balance may be difficult; many companies will under-disclose, while others may over-disclose. Companies should therefore only disclose what is accurate and relevant to the company. The US Chamber of Commerce, in their ESG Reporting Best Practices, suggests things in a similar vein: do not include ESG metrics into SEC filings; only disclose what is useful to the intended audience and ensure that ESG reports are subject to a “rigorous internal review process to ensure accuracy and completeness.”

Key Takeaway 3: ESG Reporting Can Also be Beneficial for Companies

The threat of potential litigation should not dissuade companies from disclosing sustainability frameworks and metrics. Not only are companies facing investor pressure to disclose ESG metrics, but such disclosure may also incentivize companies to improve internal risk management policies, internal and external decisional-making capabilities and may increase legal and protection when there is a duty to disclose. Moreover, as ESG investing becomes increasingly popular, it is important for companies to be aware that robust ESG reporting, which in turn may lead to stronger ESG ratings, can be useful in attracting potential investors.

Best Practices: Companies should try to understand key ESG rating and reporting methodologies and how they match their company profile.

The growing interest in ESG metrics has meant that the number of ESG raters has grown exponentially, making it difficult for many companies to understand how each “rater” calculates a company’s ESG score. Resources such as the Better Alignment Project run by the Corporate Reporting Dialogue, strive to better align corporate reporting requirements and can give companies an idea of how frameworks such as CDP, CDSB, GRI and SASB overlap. By understanding the current ESG market raters and methodologies, companies will be able to better align their ESG disclosures with them. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce report noted above also suggests that companies should “engage with their peers and investors to shape ESG disclosure frameworks and standards that are fit for their purpose.”

À la prochaine…

Divulgation Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Et le « E » des ESG ?

Ivan Tchotourian 9 juillet 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Voilà une belle question abordée dans ce billet du Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance « What Board Members Need to Know about the “E” in ESG » (par Sheila M. Harvey, Reza S. Zarghamee et Jonathan M. Ocker, 9 juillet 2020) !

Extrait concernant les CA :

Board Responsibilities

Traditionally, a company’s board will manage corporate governance risks and executive compensation. The practical need to expand these responsibilities to account for environmental stewardship and risk management is a relatively new phenomenon, and many boards are not yet up to speed.

The first step toward properly addressing environmental matters is for the board to collaborate with management to identify the different ways in which the company’s businesses and operations interface with environmental issues. The aim here is to think expansively. For purposes of ESG, environmental matters extend beyond regulatory compliance and impacts on natural resources to include concepts such as environmental justice, carbon footprints, supply chains and product stewardship.

Consistent with this approach, an equally broad realm of potential environmental risks also should be considered. These may include the potential to cause environmental contamination and natural resource damages, which may trigger not just cleanup liabilities but also disclosure requirements in financial statements. Also relevant is the potential for business operations to be disrupted by environmental factors such as climate change.

Once potential environmental risks are identified, assessments should be made regarding their materiality and the existence of standing corporate policies and procedures to address them. Where such policies are lacking, they should be developed and implemented. Moreover, determinations should be made about how the company will present itself to investors, regulators and society to adequately inform them of potential environmental risks, avoid reputational harm and increase long-term value.

There is no one-size-fits-all solution, and companies have different environmental profiles. Each will have to find its own way, but the board should make sure that management devotes the appropriate resources to addressing environmental matters, understands environmental disclosure requirements and standards and ranking systems, and takes a proactive approach to protecting the company’s reputation from an environmental standpoint.

This is a multifaceted paradigm that requires open lines of communication between management and the board at all times. Moreover, because not every board member can be an ESG expert, we recommend that the appropriate committee be tasked in its charter with spearheading the environmental risk area for the board.

Points à retenir :

- Corporate boards should partner with management to ensure appropriate and regular oversight of environmental issues critical to the long-term economic success and reputation of the company.

- Either the board or an authorized committee should receive briefings on environmental matters/risks that may jeopardize a company’s reputation and corrective action undertaken to address those risks.

- Management should monitor environmental disclosures and rankings of peer firms and consult with the board on how to improve their company’s standing relative to competing firms and in terms of stakeholder expectations.

À la prochaine…

divulgation extra-financière

La Coalition canadienne pour une bonne gouvernance publie son « Directors’ E&S Guidebook »

5 juin 2018 Loïc Geelhand de Merxem

Le 29 mai dernier, la Coalition canadienne pour une bonne gouvernance (« CCGG ») a publié son guide pratique en matière sociale et environnementale. Celui-ci contient diverses recommandations pour une plus grande surveillance du conseil d’administration ainsi qu’une meilleure divulgation de l’information en matière sociale et environnementale (« EG[1] ») provenant de l’entreprise. Le rapport et le communiqué de presse (en anglais) sont accessibles ici

Pour rappel, la CCGG représente divers investisseurs au Canada. Caisses de retraite, organismes de placement collectif, gestionnaire de capitaux ou encore investisseurs individuels, elle gère ainsi plus de 3 000 milliards de dollars d’actifs[2] notamment dans les grandes sociétés de l’indice S&P/TSX. L’objectif de la CCGG est de « promouvoir de bonnes pratiques de gouvernance dans les sociétés dont ses membres détiennent des actions[3] » puisque bien souvent, bonne gouvernance rime avec création de valeur pour les actionnaires.

1. La prise en compte des critères « ESG » par les investisseurs institutionnels

La coalition, par la publication de ce guide pratique, démontre une préoccupation de plus en plus importante pour les investisseurs : celle de la prise en compte des problèmes sociaux et environnementaux comme critère essentiel à la création de valeur sur le long terme[4].

Les investisseurs institutionnels sont de plus en plus sollicités afin de mettre en avant ces principes. Il suffit de prendre pour exemple les développements en France à ce sujet avec l’article 173 de la Loi sur la transition énergétique[5] ou le dernier rapport de la Commission européenne sur la finance durable[6].

Promouvoir les critères ESG en amont chez les investisseurs permet une meilleure sensibilité et réception de ces principes par les entreprises. De plus, la prise en compte des critères ESG par ces derniers permet une meilleure performance de l’entreprise. « The oversight of all significant risk factors is a core function of a corporate board. Every company should have a robust risk management system that includes E&S factors as a fully integrated part of the indentification and assessment process[7] ».

Le rapport développe huit domaines[8] où ces critères peuvent être développés au sein de l’entreprise :

- La culture d’entreprise ;

- La gestion des risques ;

- La stratégie d’entreprise ;

- La composition du conseil d’administration ;

- La structure du conseil d’administration ;

- Les pratiques dudit conseil ;

- L’évaluation de la performance et les incitatifs ;

- Ainsi que le reporting aux actionnaires.

L’objectif de ce guide est d’instaurer un dialogue entre entreprises et investisseurs autour des problématiques ESG afin d’améliorer la transparence et la gestion de ces informations sur le long-terme[9]. Cela passe non seulement par le reporting, mais aussi par le dialogue entre le conseil d’administration et ceux qui gèrent au quotidien l’entreprise, les directeurs. Ce dialogue interne de l’entreprise est en effet essentiel pour bien comprendre les enjeux ESG d’une entreprise qui lui sont propres. Le choix du modèle de reporting est illustratif de ce besoin d’adaptation : le modèle différera d’une entreprise à une autre, d’un secteur à un autre. Le but est alors une réelle prise en main et compréhension de ces problématiques par l’entreprise. En faisant cela, le reporting qui découlera de ce processus ne sera que plus efficace, et répondra de manière efficiente aux attentes des investisseurs.

2. Le reporting extra-financier comme portrait « ESG » de l’entreprise

L’objectif principal de la divulgation extra-financière est de montrer la prise en compte des risques et opportunités ESG sont identifiés et gérés, mais aussi comment les actions ESG permettent de créer de la valeur pour les actionnaires. Le but est ainsi d’intégrer le reporting extra-financier dans la stratégie globale de l’entreprise, notamment dans ses objectifs financiers et opérationnels[10].

L’entreprise doit pouvoir communiquer sur les critères ESG de manière claire, précise, et les données doivent pouvoir être vérifiable tout en étant pertinent au regard des activités l’entreprise[11]. De plus, il est impératif pour l’entité concernée d’expliquer comment elle va intégrer ces risques et opportunités dans sa stratégie globale. Cette divulgation devient essentielle pour l’investisseur, puisqu’elle est indirectement concernée par ces risques.

« Investor needs may differ from other stakeholders. Investors are focused on long-term, sustainable value, so it is important for a company to articulate how their E&S-related activities create value for the business and shareholders. Boards need to understand and articulate why they undertake sustainability initiatives as it relates to corporate value.[12]

L’intention de divulguer des données ESG devient essentielle. Cependant, la manière de communiquer ces informations peut diverger entre entreprises ou investisseurs. La CCGG recommande ainsi d’agir en deux étapes. Dans un premier temps, il s’agit choisir un cadre de référence, c’est-à-dire d’établir les thématiques qui seront abordées. Dans un deuxième temps, il faut choisir un modèle de références et d’indicateurs afin de rendre compte, clairement, de ces thématiques au sein de l’entreprise.

En ce qui concerne le cadre (Étape 1), la CCGG recommande d’utiliser le modèle de la Financial Stability Board (“FSB”), combiné aux travaux de la Task Force on Climate-related financial disclosures (“TCFD”) afin de communiquer ces informations ESG. La FSB est un organisme regroupant de nombreuses autorités financières nationales et organisations internationales afin d’élaborer des normes dans le domaine de la stabilité financière. La TCFD quant à elle, s’intéresse plus particulièrement aux risques climatiques.

Pour les indicateurs et références (Étape 2), il existe de nombreuses normes qui peuvent s’intéresser plus particulièrement à communiquer avec les investisseurs comme les modèles IR (Integrated reporting) ou CDP (Carbon disclosure project). Rien n’empêche aussi de vouloir communiquer de manière plus large, c’est-à-dire aux parties prenantes, grâce aux modèles ISO ou GRI[13]. La CCGG recommande particulièrement le modèle GRI ou CDP.

Pour finir, celle-ci recommande quatre pratiques autour du reporting[14] :

– Le reporting doit se faire dans l’objectif de répondre aux besoins des investisseurs et de manière détaillée en abordant la gouvernance, la stratégie et la gestion de risque de manière suffisamment précise grâce à des indicateurs, détails ou information supplémentaires.

– Les données ESG doivent être claires, mesurables, prospectives et comparables.

– Le cadre du reporting choisit par l’entreprise et son raisonnement doit être expliqué dans les rapports de celle-ci.

– Si le rapport extra-financier est séparé du reporting financier, il doit contenir suffisamment d’informations financières afin de pouvoir être exploitable par les investisseurs. Ce rapport doit de plus, pouvoir être raisonnablement vérifié et resté sous le contrôle du conseil d’administration afin d’assurer la véracité des informations communiquées.

Le reporting devient alors essentiel pour l’entreprise et l’investisseur. Son existence et son utilité sont évidentes, mais comme le montrent les recommandations de la CCGG, des améliorations doivent être faites quant à la conception des rapports, la méthode et la présentation de toutes ces données ESG. La mise en place de ce guide par un groupement d’investisseurs marque aussi la place de plus en plus prégnante des investisseurs autour de ces problématiques.

[1] Ou « ESG » si l’on inclut la Gouvernance.

[2] CCGG, communiqué, « Canadian Coalition for Good Governance Issues Guidelines for Boards of Directors to Ensure Effective

Oversight and Disclosure of Environmental and Social Matters » (29 mai 2018), en ligne :

< https://admin.yourwebdepartment.com/site/ccgg/assets/pdf/press_relase_-_laucn_final2.pdf>.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Loi n° 2015-992 du 17 août 2015 relative à la transition énergétique pour la croissance verte, JO, 18 août 2015, 14263.

[6] Commission européenne, communiqué, « Finance durable : plan d’action de la Commission pour une économie plus verte et plus propre » (8 mars 2018).

[7] CCGG, supra note 2.

[8] CCGG, rapport, « The Directors’ E&S Guidebook » (Ma 2018), à la p 4, en ligne :

< https://admin.yourwebdepartment.com/site/ccgg/assets/pdf/The_Directors__E_S_Guidebook.pdf>.

[9] Ibid à la p 21.

[10] Ibid à la p 17.

[11] Ibid à la p 18.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Greenstone, ebook, « Non-Financial Reporting Frameworks —A Closer Look at the Top 7 » (July 2014), à la p 13, en ligne : < https://www.greenstoneplus.com/non-financial-reporting-framework-ebook>.

[14] Il s’agit en l’espèce des recommandations n°26, 27, 28 et 29 à la p 20-21 du guide.