Gouvernance

Divulgation finance sociale et investissement responsable Gouvernance Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Fonds de pension hollandais : fronde contre le greenwashing

Ivan Tchotourian 23 novembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

IPE Magazine de novembre 2020 publie un article de Tjibbe Hoekstra initulé : « Survey: Dutch pension funds accuse asset managers of greenwashing » (16 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Some asset managers do not invest as responsibly as they claim, a number of Dutch pension funds have said.

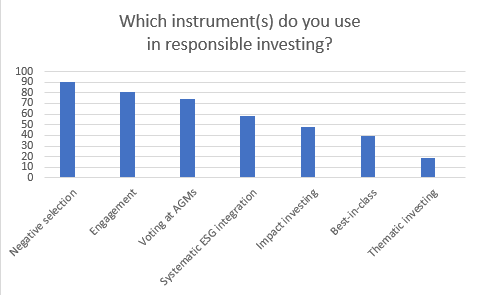

In a survey among 31 Dutch pension funds carried out by Dutch pensions publication Pensioen Pro, six in 10 Dutch pension funds agreed with the statement that some asset managers engage in greenwashing.

None of the participating pension funds, with combined assets under management worth €1.2trn, disagreed with the statement that greenwashing is a problem.

An important reason asset managers are being given the chance to engage in greenwashing is a lack of commonly agreed environmental, social, and corporate governance (ESG) standards, many pension funds believed.

Some 56% of respondents even saw the absence of a common ESG definition as a threat to responsible investing, the survey found.

Responsible investing is a rising trend in the Dutch pension sector, with 87% of the surveyed funds now having their own sustainable investment policy. The remaining 13% have outsourced this to their fiduciary manager.

None of the surveyed funds said they have no dedicated policy for responsible investing.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Missing in Friedman’s Shareholder Value Maximization Credo: The Shareholders

Ivan Tchotourian 25 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Luca Enriques a publié un intéressant billet sur l’Oxford Business Law Blog : « Missing in Friedman’s Shareholder Value Maximization Credo: The Shareholders » (25 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

What Friedman’s Essay Says

As Alex Edmans has noted here,

‘Friedman’s article is widely misquoted and misunderstood. Indeed, thousands of people may have cited it without reading past the title. They think they don’t need to, because the title already makes his stance clear: companies should maximize profits by price-gouging customers, underpaying workers, and polluting the environment’.

That is not, of course, what Friedman wrote. According to Friedman:

- Talking about the ‘social responsibility of business’ makes no sense because the responsibility lies with people. Public corporations are legal persons and may have their responsibilities, but they act through their directors and managers. Therefore, attention must be focused on the responsibilities of such players.

- Managers are employees of corporations, which in turn are owned by their shareholders. Therefore, managers must act in accordance with the wishes of the shareholders. Unless the shareholders themselves explicitly determine an altruistic purpose, this means ‘conduct[ing] the business in accordance with [shareholders’] desires, which generally will be to make as much money as possible while conforming to their basic rules of the society, both those embodied in law and those embodied in ethical custom’.

- If managers also had a social responsibility, they would find themselves in the position of having to act against the interests of shareholders, for example by hiring the ‘hardcore’ unemployed to combat poverty instead of hiring the most capable workers. By doing so, they would spend shareholders’ money to pursue a general interest. In other words, they would impose a tax on shareholders and also decide how to use its proceeds. Yet, it is countered, if there are serious and urgent economic and environmental problems, then it is necessary that managers face them without waiting for politicians’ action, which is always late and imperfect. According to Friedman, it is undemocratic for private individuals using other people’s money (and, importantly, exploiting the monopolistic rents of the large corporations they lead) to impose on the community their political preferences on how to solve urgent economic and environmental problems, which should instead be addressed through the democratic process.

- The market is based on the unanimity rule; in ‘an ideal free market’, there is no exchange without the consent of those who participate in it. Politics, on the other hand, operate according to the conformity principle, whereby a majority binds the dissenting minority. The intervention of politics is necessary because the market is imperfect. But the social responsibility doctrine would extend the mechanisms of politics to the market sphere, since a private subject (enjoying some monopoly power) would impose its political will on others.

- Often, the idea of corporate social responsibility (CSR) is just a public relations exercise to justify managerial choices already consistent with the interests of shareholders. Looking after the well-being of employees, devoting resources to the firm’s local communities, and so on may well be (and, as a rule, will be) in the long-term interest of corporations. Indeed, cloaking these actions under the label of CSR, as it was fashionable to do in 1970 (and is again today), can in itself contribute to increasing profits.

Missing from Friedman’s Picture: The Shareholders

Friedman’s essay assigned a totally passive role to what he calls the corporation’s ‘owners’ or ‘the employers’—that is, the shareholders. They are merely the beneficiaries of directors’ duty to increase profits, but they have no role to play in pursuing that very goal other than (as he notes in passing) when they elect the board.

That’s understandable. When Friedman wrote his piece, the shareholders of US companies were mostly individuals and rarely voted at annual meetings other than to rubber-stamp managers’ proposals. Today, a large majority of listed firms’ shares are held by institutional investors—that is, managers of other people’s funds. Institutions have become key players at US (as well as non-US) listed corporations (eg, this OECD study with data from across the world), because they regularly vote portfolio shares at shareholder meetings. And their pro-management vote is nowadays anything but certain.

This creates one additional layer of employee/employer relationships, to use Friedman’s terminology (today, we would say principal/agent relationships): the one between the institutions holding shares or (as Friedman saw it) their own managers, and the individuals (usually workers and pensioners) whose funds the managers invest. (To be sure, it is often more complicated than that because some institutions, such as pension funds, often delegate their asset management to other institutions; but this is not relevant for the purposes of my analysis).

Friedman’s essay raises the question: is there any room for asset managers to assume social responsibility duties in deciding how to invest and how to vote? In Friedman’s logic, the answer should be ‘no’, and it’s easy to imagine that he would chastise those fund managers who portray themselves (not always veritably) as socially responsible investors. Like corporate managers, fund managers manage other people’s money and should not grant themselves the license to make political choices, which will inevitably please some of their beneficiaries and not others. Their only goal should be giving their clients the highest returns on the funds invested.

Of course, much like a corporation can be set up with an altruistic (or mixed) purpose, so can asset management products expressly be marketed as socially responsible or ethically-investing. Intuitively, investors in such funds expect them to invest and vote in accordance with the socially responsible commitments undertaken. But absent a CSR connotation—namely, if the mutual fund has been marketed as a tool for generating financial returns—fund managers have to assume that the fund’s investors have a financial objective in mind and do not expect their own political preferences to be promoted by their fund manager, especially if that comes to the detriment of their return. Whether implicitly or explicitly, that’s the bargain with each of the fund shares buyers.

However, things are not always so straightforward. Passive institutional investors replicating indexes and, therefore, holding the entire market rather than picking stocks now hold more than 40 percent of the US stock market. As Madison Condon and Jack Coffee have noticed—here and here, respectively—for investors of that kind, portfolio value maximization may well mean pushing for ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) policies at the individual company level that, while not necessarily profitable for that company, will increase portfolio returns by making other companies more profitable. Think, for instance, of systemically important financial institutions adopting more conservative risk management policies that significantly reduce the chances of a potentially devastating financial crisis.

Hence, the overlap between socially responsible and profit-maximizing behavior, which Friedman himself acknowledged to be present at the individual company level and criticized only as being politically dangerous, is now even more pervasive at the institutional shareholder level.

In theory, all portfolio value maximizers’ decisions on ESG matters should be based on an assessment of the effects that the adoption of a given policy by an individual portfolio company would have, both on its value and on the value of the totality of other portfolio companies. Because ESG policies require widespread adoption to be effective, different scenarios will have to be elaborated and factored in to estimate those effects. Multiple other variables will have to be considered and a number of questionable assumptions made.

Passive investors, like any organization, are unlikely to have the human and financial resources to fully engage with this kind of assessment, let alone reach solid conclusions. And it would be naïve to assume that political preferences do not affect the simplified analysis they inevitably resort to in determining their ESG preferences.

Owing to shareholder pressure and/or managers’ desire to retain their jobs, the ESG preferences of portfolio value-maximizing institutions may well trickle down to the individual portfolio company level. Under what conditions that is the case will depend on a number of factors, including whether the company is protected from competition, undiversified shareholders’ stakes in the company, how politically divisive the socially responsible action is, and so on. Yet in some cases, and in respect of some of the socially and politically sensitive issues, managers will yield to those preferences. Given Friedman’s premise that ‘increasing profits’ must be the only corporate goal because the shareholders are the owners/employers, there is some irony to that.

Irony aside, today’s corporate world is very different from the one Milton Friedman wrote in. Yet, his essay still provides a useful framework for understanding the implications of managing companies for one purpose or another. And perhaps also for answering the reframed question of whether corporate managers should cater to the preferences of their portfolio-value-maximizing indexing investors when making decisions on behalf of their corporations.

À la prochaine

engagement et activisme actionnarial Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement Nouvelles diverses objectifs de l'entreprise parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Les investisseurs institutionnels réclament de la responsabilité !

Ivan Tchotourian 6 avril 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

L’ICCR (Interfaith Center on Corporate Responsibility) américain vient de prendre une position intéressante dans le contexte de la pandémie de Coronavirus : elle exhorte les entreprises à plus de responsabilité et fait connaître ses 5 priorités. Preuve une fois de plus que l’engagement des investisseurs institutionnels en faveur de la RSE est présent !

Global institutional investors comprising public pensions, asset management firms and faith-based funds issued a Statement on Coronavirus Response calling on the business community to step up as corporate citizens, and recommending measures corporations can take to protect their workforces, their communities, their businesses and our markets as a whole while we all confront the Coronavirus crisis.

Extrait :

1. Provide paid leave: We urge companiesto make emergency paid leave available to all employees, including temporary, part time, and subcontracted workers. Without paid leave, social distancing and self-isolation are not broadly possible.

2. Prioritize health and safety: Protecting worker and public safety is essential for maintaining business reputations, consumer confidence and the social license to operate, as well as staying operational. Workers should avoid or limit exposure to COVID-19 as much as possible. Potential measures include rotating shifts; remote work; enhanced protections, trainings or cleaning; adopting the occupational safety and health guidance, and closing locations, if necessary.

3. Maintain employment: We support companies taking every measure to retain workers as widespread unemployment will only exacerbate the current crisis. Retaining a well-trained and committed workforce will permit companies to resume operations as quickly as possible once the crisis is resolved. Companies considering layoffs should also be mindful of potential discriminatory impact and the risk for subsequent employment discrimination cases.

4. Maintain supplier/customer relationships: As much as possible, maintaining timely or prompt payments to suppliers and working with customers facing financial challenges will help to stabilize the economy, protect our communities and small businesses and ensure a stable supply chain is in place for business operations to resume normally in the future.

5. Financial prudence: During this period of market stress, we expect the highest level of ethical financial management and responsibility. As responsible investors, we recognize this may include companies’ suspending share buybacks and showing support for the predicaments of their constituencies by limiting executive and senior management compensation for the duration of this crisis.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement Nouvelles diverses

Retraite : des investisseurs institutionnels toujours plus puissants

Ivan Tchotourian 20 mars 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Vraiment intéressant cet article de Le Monde : « Après BlackRock, Vanguard convoite les retraites européennes » (10 mars 2020). À l’instar de l’Amérique du nord, de gros joueurs veulent faire leur apparition sur le marché et vont devoir placer leurs fonds dans des entreprises. Le capitalisme à double étage comme l’appelait Philippe Bissara a un bel avenir devant lui !

Résumé

En décembre 2019, le grand public français a soudain découvert BlackRock. L’énorme société de gestion américaine, la plus importante au monde, qui gère 7 500 milliards de dollars (6 500 milliards d’euros) d’encours, s’est retrouvée accusée d’agir en sous-main pour influencer la réforme des retraites. Jean-Luc Mélenchon fustige désormais les « blackrockistes » : « C’est BlackRock qui se trouve là, derrière tous ces articles [de loi] », dénonçait le leader de La France insoumise, le 9 février, devant une commission de l’Assemblée nationale.

Et voilà que Vanguard, autre énorme société de gestion américaine, avec 5 600 milliards de dollars d’encours, se lance dans le débat. Mardi 10 mars, elle publiait un « manifeste » incitant les Européens à épargner davantage. « Les habitants de l’Union européenne n’épargnent pas correctement pour leur retraite et, chez Vanguard, nous pensons qu’il y a certaines choses qui peuvent être faites pour les aider », explique au Monde Sean Hagerty, le directeur de Vanguard pour l’Europe.

À la prochaine…

engagement et activisme actionnarial Nouvelles diverses objectifs de l'entreprise Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Nos étudiants publient : « Maximisation de la valeur actionnariale : une nouvelle idéologie ? » Retour sur un texte de Lazonick et O’Sullivan (billet de Guillaume Giguère et Pierre-Luc Godin)

Ivan Tchotourian 16 juillet 2018 Ivan Tchotourian

Le séminaire à la maîtrise de Gouvernance de l’entreprise (DRT-7022) dispensé à la Faculté de droit de l’Université Laval entend apporter aux étudiants une réflexion originale sur les liens entre la sphère économico-juridique, la gouvernance des entreprises et les enjeux sociétaux actuels. Le séminaire s’interroge sur le contenu des normes de gouvernance et leur pertinence dans un contexte de profonds questionnements des modèles économique et financier. Dans le cadre de ce séminaire, il est proposé aux étudiants depuis l’hiver 2014 d’avoir une expérience originale de publication de leurs travaux de recherche qui ont porté sur des sujets d’actualité de gouvernance d’entreprise. C’est dans cette optique que s’inscrit cette publication qui utilise un format original de diffusion : le billet de blogue. Cette publication numérique entend contribuer au partager des connaissances à une large échelle (provinciale, fédérale et internationale). Le présent billet est une fiche de lecture réalisée pares derniers sur le primat de la valeur actionnariale et relisent l’étude de William Lazonick et Mary O’Sullivan « Maximizing shareholder value: a new ideology for corporate governance ». Je vous en souhaite bonne lecture et suis certain que vous prendrez autant de plaisir à le lire que j’ai pu en prendre à le corriger.

Ivan Tchotourian

Le texte « Maximizing shareholder value: a new ideology for corporate governance »[1], écrit par les auteurs William Lazonick et Mary O’Sullivan, a pour but de mettre en perspective l’évolution et l’impact de l’idéologie entourant la maximisation de la valeur des actionnaires en tant que principe ancré de gouvernance corporative aux États-Unis depuis les années 80. Plus précisément, les auteurs tracent une analyse historique de la transformation d’une stratégie corporative s’orientant davantage vers la rétention des bénéfices de l’entreprise et de leur réinvestissement dans la croissance corporative (ci-après « retain and reinvest »), en une stratégie corporative beaucoup plus axée sur la réduction des effectifs de l’entreprise et la distribution des bénéfices des sociétés par actions aux actionnaires (ci-après « downsize and distribute »). Ultimement, les auteurs en viennent à se demander si cette nouvelle stratégie est appropriée pour diriger la gouvernance des entreprises.

Une nouvelle stratégie ?

Dans les années 60 et 70, deux problématiques principales ont poussé les entreprises à réfléchir à une nouvelle stratégie corporative à adopter au détriment de celle du retain and reinvest : l’amplification de la croissance de la société et la progression de nouveaux concurrents. Relativement à la première problématique, l’envergure que prenaient les entreprises, ainsi que leur subdivision, engendra des difficultés au niveau de la prise de décisions, laquelle s’est effectuée de plus en plus de manière centralisée. Relativement à la seconde problématique, l’environnement macroéconomique instable et l’ascension d’une compétition internationale innovante occasionnée notamment par la production de masse des industries automobiles et électroniques ont amené les entreprises américaines à faire une prise de conscience sur la nécessité d’améliorer leurs procédés.

Dans la foulée des conséquences du retain and reinvest, des économistes financiers américains ont développé dans les années 70 une nouvelle approche dans le domaine de la gouvernance d’entreprise connue sous le nom de « théorie de l’agence » (« agency theory »). Ces économistes considéraient qu’il était préférable pour les organisations qu’elles laissent le marché faire son œuvre en s’abstenant d’intervenir excessivement dans l’allocation des ressources. Selon cette nouvelle théorie, les actionnaires sont les principaux intéressés tandis que les dirigeants sont leurs agents, qui doivent agir dans leur intérêt. La limitation du contrôle des dirigeants sur l’allocation des ressources et le renforcement de l’influence du marché forcerait ainsi les dirigeants à agir dans l’intérêt des actionnaires en visant davantage la maximisation de la valeur des actions. En addition, dans cette même période, la poursuite d’un objectif de création de valeur pour les actionnaires dans l’économie américaine a trouvé du support auprès de nouveaux acteurs : les investisseurs institutionnels. Ces investisseurs institutionnels, incarnés par les fonds mutuels, les fonds de pension et les compagnies d’assurance-vie, ont rendu possibles les prises de contrôle préconisées par les théoriciens de l’agence et ont donné aux actionnaires un pouvoir collectif important pour influencer les rendements et la valeur des actions qu’ils détenaient. L’accroissement des possibilités de financement, notamment avec le recours aux obligations pourries (« junk bonds »), un instrument spéculatif à haut taux de risque, a permis aux investisseurs institutionnels et aux institutions d’épargne et de crédit de devenir rapidement des participants centraux dans cette prise de contrôle hostile. Le résultat a été l’émergence d’un puissant marché pour le contrôle d’entreprise.

Au nom de la création de la valeur actionnariale

Dans une tentative d’accroître le rendement sur les capitaux propres, les années 80 et 90 ont été marquées par une réduction significative de la main-d’œuvre, par une augmentation considérable des dividendes distribués (même s’ils n’étaient pas toujours précédés par une augmentation de profits) et par des rachats d’actions importants et récurrents. L’implantation de cette stratégie de type downsize and distribute a d’ailleurs été soutenue par le fait que les dirigeants recevaient de plus en plus d’actions ou d’autres types de bonus en guise de rémunération depuis les années 50. En effet, cette stratégie a mené à l’explosion de la rémunération des hauts dirigeants.

Cependant, les rendements élevés des actions de sociétés, en plus de la réduction de la main-d’œuvre sous la stratégie du downsize and distribute, n’ont fait qu’exacerber l’inégalité des revenus aux États-Unis[2]. Pour réduire l’inégalité dans la distribution des richesses, il faut que les sociétés qui préconisent la stratégie downsize and distribute s’engagent à adopter certaines stratégies requérant qu’elles fassent aussi du retain and reinvest, particulièrement en faveur des cols bleus. Sans l’adoption de telles stratégies, il faudra alors aussi se demander si les États-Unis possèderont l’infrastructure technologique requise pour être prospères au 21e siècle. Par ailleurs, bien que l’adoption par les entreprises américaines d’une politique de downsize and distribute a fourni l’élan sous-jacent au boom boursier des années 90, il n’en demeure pas moins que le taux soutenu et rapide de la hausse des cours est principalement le résultat d’un afflux massif par les fonds mutuels en équité au sein du marché boursier.

Conclusion

Les auteurs clôturent leur texte en affirmant que le boom du marché boursier n’a pas mis plus de capitaux à la disposition de l’industrie, l’émission d’actions ayant demeurée faible, mais plutôt causé une hausse de la consommation par l’abondante distribution des revenus corporatifs. Se référant à des exemples de compagnies américaines dominantes dans leur secteur[3], lesquelles employaient les principes du retain and reinvest, ils retiennent de l’expérience américaine que la poursuite de la maximisation de la valeur des actionnaires est une stratégie appropriée si l’on souhaite ruiner une entreprise, voire même une économie. Il serait donc intéressant de voir si, aujourd’hui en 2017, la maximisation de la valeur des actionnaires est une stratégie de gouvernance qui a fait ses preuves et qui bénéficie d’une validation auprès des experts dans les milieux concernés[4].

Guillaume Giguère et Pierre-Luc Godin

Étudiants du cours de Gouvernance de l’entreprise – DRT-7022

[1] William Lazonick et Mary O’Sullivan, « Maximizing shareholder value: a new ideology for corporate governance » (2000) 29:1 Economy and Society 13.

[2] Les ménages de classe moyenne détenant rarement des actions de sociétés.

[3] Causé notamment par l’investissement, dans ces fonds mutuels, des générations âgées ayant accumulés du capital durant les périodes marquées par le retain and reinvest.

[4] Il semblerait qu’au contraire, le principe de la maximisation de la valeur des actionnaires connaît aujourd’hui encore de vives critiques quant à son efficacité et ses effets. Voir à cet effet les articles suivants : Steve Denning, « Making Sense Of Shareholder Value: ‘The World’s Dumbest Idea’ », Forbes (17 juillet 2017); Steve Denning, « The ‘Pernicious Nonsense’ Of Maximizing Shareholder Value », Forbes (27 avril 2017); Peter Atwater, « Maximizing Shareholder Value May Have Gone Too Far », Time (3 juin 2016). D’autres articles vont, quant à eux, à la défense du principe et misent sur la création de la valeur des actionnaires sur le long terme et non au court terme : Michael J. Mauboussin et Alfred Rappaport, « Reclaiming The Idea of Shareholder Value » (2016) Harvard Business Review; Alfred Rappaport, « Ten Ways to Create Shareholder Value » (2006) Harvard Business Review.

engagement et activisme actionnarial Nouvelles diverses

Nouvelle leçon de Larry Fink sur le long-terme

Ivan Tchotourian 6 février 2017

Le blogue newsfinance expose la récente position prise par le gérant de l’énorme fonds Blackrock : « Quand le pape de la finance s’adresse aux grands patrons » (newsfinance.fr, 24 janvier 2017). Une position riche d’enseignement !

Si Larry Fink « engage » publiquement les grandes sociétés dont Blackrock est un actionnaire parfois significatif, ce n’est donc pas pour leur demander de pressurer plus leurs salariés pour donner plus de jus aux actionnaires, mais plutôt pour les appeler à la responsabilité et à une stratégie de long-terme. Et si les financiers sont souvent accusés de court-termisme, Larry Fink avance un contre-argument intéressant. « Comme les actifs de nos clients sont souvent investis dans des produits indexés à des indices – et que nous ne pouvons pas vendre ces titres tant qu’ils demeurent dans l’indice – nos clients sont assurément des investisseurs de long terme », écrit-il. Mais il avertit aussi les chefs d’entreprise qu’il ne faut pas confondre investissement de long terme et patience infinie ! Au besoin, et faute d’un dialogue constructif, Blackrock peut ainsi voter son droit de vote pour sanctionner un management déficient ou des rémunérations managériales « non alignées » avec les intérêts des actionnaires.

(…) Mais il est aussi intéressant de voir l’homme le plus puissant de la gestion d’actifs mondiale recommander aux grands patrons de s’intéresser de plus près aux facteurs ESG (environnement, social, gouvernance) dans leurs décisions, leur indiquant notamment de veiller au bien-être de leurs salariés. « Les événements de l’année passée ne font que démontrer de manière renforcée combien le bien-être des employés d’une entreprise est critique pour son succès à long terme », écrit Larry Fink. Un point de vue que ne contrediront pas les gérants de Sycomore, un acteur de la gestion d’actifs sans doute mille fois plus petit que Blackrock, mais convaincu de ce sujet au point d’avoir lancé un fonds baptisé « Happy @ Work », sélectionnant les sociétés dans lesquelles il investi sur ce critère précis.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

engagement et activisme actionnarial Gouvernance objectifs de l'entreprise

Des actionnaires de plus en plus actifs : un exemple

Ivan Tchotourian 7 novembre 2016

Intéressant article dans The Sydney Morning Herald sous la plume de Mme Vanessa Desloires intitué : « BlackRock, Vanguard, State Street are not passive on corporate governance ». Cet article illustre l’activisme croissant (et la lente disparition de la prétendue passivité des actionnaires) des actionnaires d’aujourd’hui. Il faut dire que ces derniers (devenus des investisseurs institutionnels) sont de plus en plus puissants autant financièrement qu’économiquement !

Investment behemoths BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street now hold the « balance of power » in corporate governance disputes. And they’re no longer content to be the silent giants in the background, forcing company boards to balance the long-term view of passive fund managers with the short-termism of active managers.

The underperformance of the majority of Australian active managers over the past few years, coupled with the low cost of passive funds, has driven investors into products such as exchange-traded funds en masse, with total funds under management topping $23 billion this year.

As such, the three biggest providers of passive funds, BlackRock, Vanguard and State Street, have a growing presence on company registers.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian