Responsabilité sociale des entreprises | Page 3

Gouvernance judiciarisation de la RSE normes de droit Nouvelles diverses Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Structures juridiques

Responsabilité des minières à l’étranger : un billet à parcourir

Ivan Tchotourian 17 mars 2021 Ivan Tchotourian

La professeur Elizabeth Steyn aborde la responsabilité des entreprises minières pour des actes commis à l’étranger dans un billet de blogue intitulé « Holding extractive companies liable for human rights abuses committed abroad » (Western Law, 7 décembre 2000).

Extrait

A notable driver in the movement towards stronger oversight has been allegations of abuses committed in the extractive sector. Indeed, The Business & Human Rights Resource Centre’s latest Transition Minerals Tracker (May 2020) features Glencore as a top 5 company in respect of 4 out of 6 transitional commodities (cobalt, copper, nickel and zinc) and records allegations of human rights abuses in three of these categories: cobalt (10 allegations[2]); copper (32) and zinc (14). While the copper and zinc allegations against Glencore are roughly double in number to those of its nearest competitor, it ties with the DRC state mining company, Gécamines, in respect of cobalt related human rights allegations. In unrelated news, Glencore fought unsuccessfully last week to obtain a gagging injunction pertaining to allegations of child labour made against it by the organization Initiatives multinationales responsableswith reference to its Bolivian mine in Porco.

On November 29, 2020, 50.7% of the national vote went in favour of the RBI; however, it gained a majority vote in only a third of the Swiss cantons. Observers have pointed out that this is the first time in 50 years for a referendum measure to flounder due to regional restrictions despite having attracted a nationwide popular majority.

The outcome of the referendum is thus that the Swiss Responsible Business Initiative will not come into being. However, the fact that it carried the popular vote has been described as, “a clear sign to Switzerland’s multinationals that the days of avoiding scrutiny are well and truly over.”

This is in line with developments elsewhere in the world.

In Vedanta Resources Plc & Anor v Lungowe & Ors the UK Supreme Court held in 2019 in a procedural ruling that pollution charges could proceed in the UK against Vedanta Resources, plc (“Vedenta”) and its Zambian subsidiary, Konkola Copper Mines, plc (“KCM”), notwithstanding the fact that the pollution was alleged to have taken place in Zambia and that the claimants were a Zambian community. The facts relate to the operations of the Nchanga Copper Mine in the Chingola District of Zambia.

This full-bench decision is interesting for multiple reasons. First, it is a significant ruling for multinational UK parent companies with subsidiaries operating in developing countries. Second, both Vedanta and KCM had explicitly submitted to the jurisdiction of the Zambian courts. Third, although most of the proper place indicators pointed to Zambia and despite the fact that the Court found that there would be a real risk of irreconcilable judgments between Zambia and the UK, it still ruled that the UK had jurisdiction to hear the case on the basis that the claimants were likely to suffer a substantial injustice if the matter were to proceed in Zambia. Interestingly, no criticism was levied against either the administration of justice in Zambia or its legal system. Instead, the Court held that by reason of their extreme poverty the claimants would not be able to afford funding the litigation in Zambia and that they would not be able to access a Zambian legal team of sufficient expertise, experience and resources to pursue such litigation in Zambia. In other words, it became an issue where access to justice considerations trumped strict procedure.

All of this is relevant in the Canadian context. In a recent Blog I addressed the settlement of the litigation in Nevsun v Araya. Of great importance remains the fact that in February 2020 the Supreme Court of Canada has in this litigation categorically opened the way for foreign plaintiffs to bring allegations in Canadian courts of human rights abuses perpetrated by foreign subsidiaries of Canadian mining companies. While the Supreme Court made no ruling on the substance of the charges given the preliminary nature of the proceedings, future plaintiffs certainly will get to address the substance of their claim far sooner. As this note has illustrated, Canada is in step with leading business and human rights developments on the international front. That is cause for celebration.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Disney : où est la RSE ?

Ivan Tchotourian 17 mars 2021 Ivan Tchotourian

Réflexion à suivre sur la RSE : malheureusement, c’est encore Disney et sa fameuse souris qui font les frais d’une tribune de Le Monde.fr… « Chez Disney, « la notion de responsabilité sociale s’efface face à la responsabilité devant l’actionnaire » » (1er décembre 2020).

Résumé

Par les temps qui courent, il vaut mieux être Donald ou Dumbo à Disneyland Paris qu’à Disneyworld Orlando. Pourtant la cruauté de la crise sanitaire est la même partout. Fermé, comme ses cousins américains en mars 2020, le parc parisien a rouvert pour l’été, avant de fermer à nouveau le 29 octobre. Réouverture envisagée seulement en février 2021. Même punition pour les parcs américains.

A la différence près que le Disneyland historique, celui de Californie, près d’Hollywood, reste fermé, sur ordre des autorités locales, tandis que celui de Floride reçoit toujours un maigre public. Dans tous les cas, les résultats sont désastreux, avec une fréquentation en baisse de plus de 80 % et donc une perte nette de 7 milliards de dollars pour cette seule activité-phare de Disney qui représente en temps normal près de la moitié de ses bénéfices et les trois quarts de ses employés.

Rapidement, la direction de l’entreprise a placé en chômage partiel l’essentiel de ses employés. Mais à Orlando, ce terme n’a pas la même signification qu’à Paris. Il correspond à une indemnisation de 275 dollars par semaine limitée à moins de trois mois, quand en France, la même mesure assure 85 % du salaire (100 % au niveau du smic) sans limite de temps. Et comme cela n’a pas suffi, l’entreprise a annoncé le 26 novembre qu’elle allait supprimer 32 000 postes, soit 4 000 de plus qu’annoncé en septembre.

Le lendemain, la direction de Disneyland Paris, qui emploie 17 000 salariés, a annoncé l’ouverture de négociations avec les syndicats sur le départ de 1 000 personnes sur une base volontaire. Et encore, il concerne un plan de réorganisation qui date d’avant le Covid, avec notamment l’arrêt de spectacles passés de mode.

À la prochaine…

Nouvelles diverses Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

RSE : pratiques des entreprises canadiennes

Ivan Tchotourian 23 novembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Numéro intéressant de Les affaires avec une série d’articles : « Des valeurs qui ont de la valeur » (11 novembre 2020).

Ceux qui accordent une grande attention à la responsabilité sociétale des entreprises (RSE) vous le diront : l’altruisme peut se transformer en actifs. L’envie de contribuer au bien commun qui anime ces entrepreneurs ne les empêche pas d’obtenir un rendement intéressant ; au contraire. Par ailleurs, si la pandémie a servi d’accélérateur au virage « solidaire » de certaines entreprises, d’autres ont seulement poursuivi sur leur lancée. Dans les deux cas, elles sortiront de la crise avec un avantage comparatif aux yeux de plusieurs.

Pour en savoir plus :

À la semaine prochaine

Nouvelles diverses Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Réputation et droit : un ouvrage

Ivan Tchotourian 12 novembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Bel ouvrage qui intéressera nos lectrices et lecteurs du blogue : « Law and reputation » (de Roy Shapira). Ce livre vient enrichir la réflexion sur le mécanisme de réputation qui est particulièrement important en matière de RSE.

Pour un résumé de cet ouvrage : ici

Résumé :

The book starts with the basic questions of what reputation is and why it is noisy. Not all bad news is created equal. Some companies and businessmen emerge from failures unscathed while others go bankrupt. To better understand why similar behaviors lead to different reputational outcomes, I break the process of reputational sanctioning into its different components: revelation, diffusion, certification, and attribution of information. Damning information has to be widely diffused so that it reaches a critical mass of stakeholders in order for the reputational sanction to be meaningful. Information that was widely diffused has to be certified as credible for the company’s stakeholders to consider it seriously. And information that was diffused and certified has to first be attributed to deep-seated flaws that are likely to reoccur in the future, in order for the company’s stakeholders to update their beliefs and act on it.

Law enforcement—both private and public—can affect the process of reputational sanctioning along each of the abovementioned stages. Think for example about internal emails exposed during the discovery stage, revealing a systematic cover-up or total lack of checks and balances throughout the corporate hierarchy. Litigation thus affects reputation by uncovering information to which market players were not privy. Litigation also affects reputations without producing new information, simply by changing the framing, credibility, and saliency of existing pieces of information. In particular, litigation shapes the scope and tenor of media coverage. To illustrate, I analyze the content analysis of the investigative projects that won the Pulitzer Prize over the last twenty years, finding that “legal sources” (court documents, regulatory investigation reports, and so on) are more often than note the key source for such media investigations (a separate article elaborates).

The bulk of the book is dedicated to specific applications of the law-and-reputation framework. Consider the following three issues, all frequently debated in this blog.

The first example comes from corporate fiduciary duty litigation. Directors may not fear the highly unlikely prospect of paying out of pocket in litigation, but they fear the nonlegal costs that come with litigation, such as having their shenanigans or faulty processes exposed in discovery and called out by an expert Delaware judge. By analyzing corporate law doctrines through their impact on information production, we get a fresh perspective on much-debated features, such as Delaware’s recent expansion of shareholders’ right to inspect the company’s books and records (I wrote elsewhere about the rise of section 220 and how it is reshaping deal negotiations and oversight duties).

A second application concerns the SEC’s enforcement practices, which became the center of national debate in the wake of the 2007-2009 financial crisis. While the existing debate revolves around the amount of money being paid or admissions being collected in SEC settlements, the reputational framework offers an alternative way to measure the effectiveness of SEC enforcement. The real problem with SEC settlements is not that the SEC leaves money on the table, but rather that the SEC leaves information on the table. Both the SEC and big-firm defendants have incentives to settle quickly and for high amounts, in exchange for limiting the public release of damning information. Such information-underproduction dynamics are good for both parties but bad for society at large. The reputational framework helps us identify solutions, like evaluating the proper scope of judicial review of SEC actions.

A third, timely issue that the reputational framework sheds light on is the proliferation of mandatory arbitration clauses that effectively waive class actions. With the blessing of the Supreme Court, mandatory arbitration provisions with class action waivers have become common in contract, consumer, and labor law. Policymakers now consider importing this trend to corporate and securities laws as well. The existing debate centers around consent and compensation: Can shareholders be held to consent to arbitration provisions in the company’s corporate governance documents? Are shareholders better off with arbitration, given that litigation currently offers them very little compensation (with high fees)? Yet the extant debate misses the forest for the trees. Even if shifting from litigation to arbitration may be good for a specific company and its investors, it may prove detrimental to the market overall. We will lose the positive externality (in the form of quality information on corporate behavior) that comes with litigation. A shift to mandatory arbitration may therefore reduce the administrative costs of litigation, but hurt the ability of the market to discipline itself. In other words, mandatory arbitration provisions may reduce the effectiveness of reputational deterrence, and therefore be bad for investors as a group.

My book thus centers around one overarching point: the law shapes behavior not just through imposing sanctions, but also through producing information. In the course of fleshing out this point and examining the interactions between law and reputation, the book contributes to various other debates beyond the ones highlighted here, such as the desirability of heightened pleading standards, or whether to assess director liability individually or collectively.

At a more general level, delving into the interconnections between law and reputation allows us to revisit the age-old policy debate over legal intervention. Two binary camps have been dominating this debate: one advocates “leaving things to the market” while the other calls for “ramping up legal sanctioning.” Yet those who oppose legal intervention fail to recognize the importance of the legal system for the functioning of market discipline. And those who advocate for more legal sanctions fail to recognize the ability of the legal system to shape behavior indirectly, without interfering with business decisions. Sometimes the most effective and realistic way to promote deterrence is not to increase legal sanctions, but to increase the quantity and quality of information production.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

The Stakeholder Model and ESG

Ivan Tchotourian 17 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

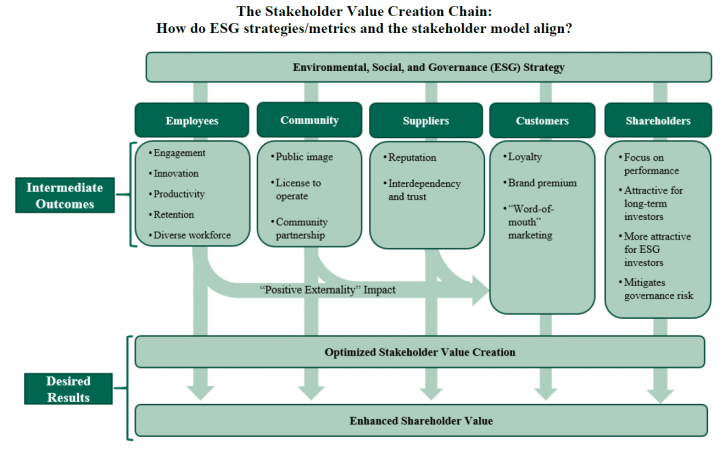

Intéressant article sur l’Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance consacré au modèle partie prenante et à ses liens avec les critères ESG : « The Stakeholder Model and ESG » (Ira Kay, Chris Brindisi et Blaine Martin, 14 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Is your company ready to set or disclose ESG incentive goals?

ESG incentive metrics are like any other incentive metric: they should support and reinforce strategy rather than lead it. Companies considering ESG incentive metrics should align planning with the company’s social responsibility and environmental strategies, reporting, and goals. Another essential factor in determining readiness is the measurability/quantification of the specific ESG issue.

Companies will generally fall along a spectrum of readiness to consider adopting and disclosing ESG incentive metrics and goals:

- Companies Ready to Set Quantitative ESG Goals: Companies with robust environmental, sustainability, and/or social responsibility strategies including quantifiable metrics and goals (e.g., carbon reduction goals, net zero carbon emissions commitments, Diversity and Inclusion metrics, employee and environmental safety metrics, customer satisfaction, etc.).

- Companies Ready to Set Qualitative Goals: Companies with evolving formalized tracking and reporting but for which ESG matters have been identified as important factors to customers, employees, or other These companies likely already have plans or goals around ESG factors (e.g., LEED [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design]-certified office space, Diversity and Inclusion initiatives, renewable power and emissions goals, etc.).

- Companies Developing an ESG Strategy: Some companies are at an early stage of developing overall ESG/stakeholder strategies. These companies may be best served to focus on developing a strategy for environmental and social impact before considering linking incentive pay to these priorities.

We note it is critically important that these ESG/stakeholder metrics and goals be chosen and set with rigor in the same manner as financial metrics to ensure that the attainment of the ESG goals will enhance stakeholder value and not serve simply as “window dressing” or “greenwashing.” [9] Implementing ESG metrics is a company-specific design process. For example, some companies may choose to implement qualitative ESG incentive goals even if they have rigorous ESG factor data and reporting.

Will ESG metrics and goals contribute to the company’s value-creation?

The business case for using ESG incentive metrics is to provide line-of-sight for the management team to drive the implementation of initiatives that create significant differentiated value for the company or align with current or emerging stakeholder expectations. Companies must first assess which metrics or initiatives will most benefit the company’s business and for which stakeholders. They must also develop challenging goals for these metrics to increase the likelihood of overall value creation. For example:

- Employees: Are employees and the competitive talent market driving the need for differentiated environmental or social initiatives? Will initiatives related to overall company sustainability (building sustainability, renewable energy use, net zero carbon emissions) contribute to the company being a “best in class” employer? Diversity and inclusion and pay equity initiatives have company and social benefits, such as ensuring fair and equitable opportunities to participate and thrive in the corporate system.

- Customers: Are customer preferences driving the need to differentiate on sustainable supply chains, social justice initiatives, and/or the product/company’s environmental footprint?

- Long-Term Sustainability: Are long-term macro environmental factors (carbon emissions, carbon intensity of product, etc.) critical to the Company’s ability to operate in the long term?

- Brand Image: Does a company want to be viewed by all constituencies, including those with no direct economic linkage, as a positive social and economic contributor to society?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to ESG metrics, and companies fall across a spectrum of needs and drivers that affect the type of ESG factors that are relevant to short- and long-term business value depending on scale, industry, and stakeholder drivers. Most companies have addressed, or will need to address, how to implement ESG/stakeholder considerations in their operating strategy.

Conceptual Design Parameters for Structuring Incentive Goals

For those companies moving to implement stakeholder/ESG incentive goals for the first time, the design parameters range widely, which is not different than the design process for implementing any incentive metric. For these companies, considering the following questions can help move the prospect of an ESG incentive metric from an idea to a tangible goal with the potential to create value for the company:

- Quantitative goals versus qualitative milestones. The availability and quality of data from sustainability or social responsibility reports will generally determine whether a company can set a defined quantitative goal. For other companies, lack of available ESG data/goals or the company’s specific pay philosophy may mean ESG initiatives are best measured by setting annual milestones tailored to selected goals.

- Selecting metrics aligned with value creation. Unlike financial metrics, for which robust statistical analyses can help guide the metric selection process (e.g., financial correlation analysis), the link between ESG metrics and company value creation is more nuanced and significantly impacted by industry, operating model, customer and employee perceptions and preferences, etc. Given this, companies should generally apply a principles-based approach to assess the most appropriate metrics for the company as a whole (e.g., assessing significance to the organization, measurability, achievability, etc.) Appendix 1 provides a list of common ESG metrics with illustrative mapping to typical stakeholder impact.

- Determining employee participation. Generally, stakeholder/ESG-focused metrics would be implemented for officer/executive level roles, as this is the employee group that sets company-wide policy impacting the achievement of quantitative ESG goals or qualitative milestones. Alternatively, some companies may choose to implement firm-wide ESG incentive metrics to reinforce the positive employee engagement benefits of the company’s ESG strategy or to drive a whole-team approach to achieving goals.

- Determining the range of metric weightings for stakeholder/ESG goals. Historically, US companies with existing environmental, employee safety, and customer service goals as well as other stakeholder metrics have been concentrated in the extractive, industrial, and utility industries; metric weightings on these goals have ranged from 5% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards. We expect that this weighting range would continue to apply, with the remaining 80%+ of annual incentive weighting focused on financial metrics. Further, we expect that proxy advisors and shareholders may react adversely to non-financial metrics weighted more than 10% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards.

- Considering whether to implement stakeholder/ESG goals in annual versus long-term incentive plans. As noted above, most ESG incentive goals to date have been implemented as weighted metrics in balanced scorecard annual incentive plans for several reasons. However, we have observed increased discussion of whether some goals (particularly greenhouse gas emission goals) may be better suited to long-term incentives. [10] There is no right answer to this question—some milestone and quantitative goals are best set on an annual basis given emerging industry, technology, and company developments; other companies may have a robust long-term plan for which longer-term incentives are a better fit.

- Considering how to operationalize ESG metrics into long-term plans. For companies determining that sustainability or social responsibility goals fit best into the framework of a long-term incentive, those companies will need to consider which vehicles are best to incentivize achievement of strategically important ESG goals. While companies may choose to dedicate a portion of a 3-year performance share unit plan to an ESG metric (e.g., weighting a plan 40% relative total shareholder return [TSR], 40% revenue growth, and 20% greenhouse gas reduction), there may be concerns for shareholders and/or participants in diluting the financial and shareholder-value focus of these incentives. As an alternative, companies could grant performance restricted stock units, vesting at the end of a period of time (e.g., 3 or 4 years) contingent upon achievement of a long-term, rigorous ESG performance milestone. This approach would not “dilute” the percentage of relative TSR and financial-based long-term incentives, which will remain important to shareholders and proxy advisors.

Conclusion

As priorities of stakeholders continue to evolve, and addressing these becomes a strategic imperative, companies may look to include some stakeholder metrics in their compensation programs to emphasize these priorities. As companies and Compensation Committees discuss stakeholder and ESG-focused incentive metrics, each organization must consider its unique industry environment, business model, and cultural context. We interpret the BRT’s updated statement of business purpose as a more nuanced perspective on how to create value for all stakeholders, inclusive of shareholders. While optimizing profits will remain the business purpose of corporations, the BRT’s statement provides support for prioritizing the needs of all stakeholders in driving long-term, sustainable success for the business. For some companies, implementing incentive metrics aligned with this broader context can be an important tool to drive these efforts in both the short and long term. That said, appropriate timing, design, and communication will be critical to ensure effective implementation.

À la prochaine…

Nouvelles diverses Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Structures juridiques

L’entreprise, un bien commun ?

Ivan Tchotourian 14 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Sympathique article « L’entreprise comme bien commun » de MM. Desreumaux et Bréchet dans la RIMHE : Revue Interdisciplinaire Management, Homme & Entreprise (2013/3 (n°7), pages 77 à 93). Pourquoi pas ?

Extrait :

Compte tenu des enjeux associés à la représentation en action de l’entreprise (questions de création et de répartition de valeur, de santé et de dynamisme d’une nation, de conception du rôle et des responsabilités des dirigeants, de gouvernance, de responsabilité sociale, de justice, etc.), il apparaît nécessaire de trouver un fondement cohérent pour une représentation dépassant les limites respectives des métaphores déjà disponibles dont l’inventaire et le reclassement mettent au jour l’opposition de visions contractualistes et « sociocognitives ». Pour de multiples raisons, la métaphore du bien commun constitue une piste potentiellement féconde. Pour l’explorer, on posera quelques repères fondamentaux sur la notion de bien commun avant d’envisager ce qui justifie d’aborder l’entreprise sur cette base. Les filiations plurielles que nous privilégierons nous conduiront ensuite à exposer plus précisément notre point de vue et à proposer une grille de lecture propre à restituer l’entreprise en termes dynamiques, exprimant les enjeux, les tensions, la façon dont se construit le bien commun : le bien commun de l’entreprise c’est le projet d’entreprise dans le cadre de la théorie de l’entreprise fondée sur le projet ou Project-Based View. C’est donc le projet dans le cadre d’une lecture processuelle, subjectiviste et multidimensionnelle.

Le projet de l’entreprise se comprend dans le cadre de la théorie de l’entreprise ou de l’action collective fondée sur le projet, ou Project-Based View (PBV), qui se présente comme une lecture subjectiviste, multidimensionnelle et développementale (Desreumaux et Bréchet, 2009). Elle représente une vision de l’entreprise fondée sur le projet à caractère englobant. Les théories dites de la firme, d’inspiration économique, ne traitent pas directement de l’entreprise réelle et de ses préoccupations de management. La théorie de l’agence ou la théorie des coûts de transaction, qui privilégient les facettes d’allocation, d’efficience et de coût, délaissent les dimensions de conception et de production de biens et de services, de même que les comportements entrepreneuriaux (Desreumaux et Bréchet, 1998 ; Bréchet et Prouteau, 2010). Elles restent pourtant largement mobilisées par les chercheurs en gestion. Les théories d’inspiration évolutionniste, qui portent leur attention sur les compétences et les connaissances de l’entreprise, nourrissent, de ce fait, une perspective plus riche. Pour autant, elles n’épuisent pas les questions d’émergence des organisations ni celles ayant trait, par exemple, aux dimensions de politique générale. Ce que propose la théorie de l’entreprise fondée sur le projet ou Project-Based View, c’est de considérer l’entreprise comme un projet collectif possédant tout à la fois un contenu éthico-politique, un contenu technico-économique (les besoins ou missions que l’entreprise entend satisfaire à travers le métier qu’elle choisit d’exercer et les compétences qu’il recouvre) et un contenu organisationnel (les voies et moyens de l’action). Considérer l’entreprise sur cette base, revient à instruire les questions des pourquoi, des quoi et des comment de l’action qui se trouvent au cœur de la constitution d’un collectif.

À la prochaine…

finance sociale et investissement responsable Nouvelles diverses

L’après Covid, la finance réinventée (?)

Ivan Tchotourian 14 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

La revue Analyse financière propose un Dossier numérique n°75 intéressant : « L’après Covid, la finance réinventée (?) ».

Au sommaire :

« Les crises jouent un rôle de régulation dans le système capitaliste »

Entretien avec Didier Coutton, INSEEC U

Navigation à vue sur le plan économique

Par Christopher Dembik, Saxo Bank

« Les actifs immatériels doivent influencer la prime de risque »

Entretien avec Éric Galiègue, commission Évaluation de la SFAF, Valquant Expertyse

« Le financement des start-up respecte une certaine logique où l’offre créée sa propre demande »

Entretien avec Florian Bercault, Estimeo et membre de la commission Évaluation de la SFAF

Les relations investisseurs à l’épreuve de la crise sanitaire

Entretien avec Olivier Psaume, président du Cliff et directeur des relations investisseurs de Sopra Steria

Quelle place pour l’ESG dans l’entreprise ?

Par Corinne Baudoin, présidente de la commission Analyse extra-financière de la SFAF, Fabienne Brilland, vice-présidente de la commission, et Martine Léonard, membre de la commission

Faut-il aussi une taxonomie « brune » ?

Par Jérôme Courcier, expert auprès de l’ORSE (Observatoire de la responsabilité sociétale des entreprises)

Private Equity : rééquilibrage et transparence pour « le monde d’après »

Par Boutros Thiery, Mercer France

G7 Pensions : ESG, SDGs, Green Growth and the road to Camp David

Par M. Nicolas J. Firzli, The World Pensions Council (WPC)

À la prochaine…