mission et composition du conseil d’administration | Page 5

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration place des salariés Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Salariés dans les CA = moins bonne performance ?

Ivan Tchotourian 24 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans The conversation, les chercheurs Nagati, Boukadhaba et Nekhili livrent un constat étonnant sur la présence des salariés dans les CA en France : oui, ils sont plus présents que par le passé, mais leur impact sur la performance de l’entreprise est critiquable… d’où la méfiance des actionnaires ! (« Salariés dans les conseils d’administration : une présence qui dérange les actionnaires… », 17 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Une gouvernance de plus en plus partenariale

Pour ce qui est des critères de gouvernance, la régulation du mode de fonctionnement du conseil d’administration n’a ainsi cessé d’évoluer ces dernières années. Celle-ci contraint davantage les entreprises à une plus grande diversité des membres du conseil d’administration, qui intègrent notamment de plus en plus de salariés.

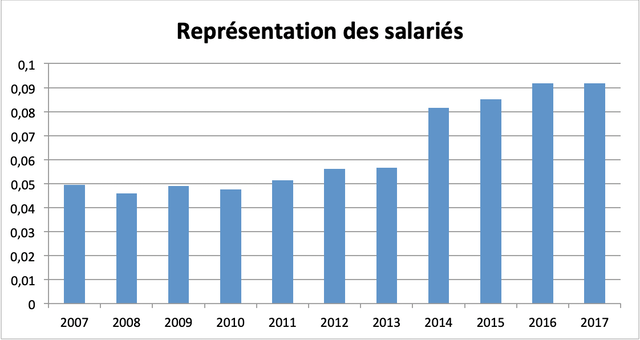

Le taux moyen de représentation des salariés dans le conseil d’administration des sociétés non financières du SBF 120 a ainsi évolué de 4,95 % en 2007 à 9,17 % en 2017 (voir graphique ci-dessous).

Une augmentation significative est notamment constatée à partir de 2014. Celle-ci s’explique par la loi n° 2013-504 de 14 juin 2013 relative à la sécurisation de l’emploi rendant obligatoire la présence d’au moins deux représentants de salariés pour les entreprises ayant des conseils d’administration de plus de 12 administrateurs et d’au moins un représentant pour les autres.

Cela témoigne de la volonté de s’orienter vers une gouvernance partenariale (stakeholders) qui s’oppose, dans ses grands principes, à la gouvernance actionnariale (shareholders).

Or, la présence de salariés au sein des conseils d’administration est généralement vue d’un mauvais œil par les actionnaires. C’est ce qui ressort de notre article de recherche publié en 2019 dans la revue International Journal of Human Resource Management sous le titre ESG Performance and Market Value : the Moderating Role of Employee Board Representation.

Cette étude porte sur un échantillon de grandes entreprises françaises non financières de l’indice SBF 120 durant la période 2007-2017.

À travers l’appréciation de la performance boursière des entreprises, les résultats de nos estimations montrent que, si le marché financier réagit positivement à la performance extrafinancière, il reste néanmoins réticent à la représentation des salariés dans le conseil d’administration.

En effet, la valeur moyenne de la performance boursière, mesurée par le Q de Tobin (rapport entre la somme de la capitalisation boursière et de la valeur de la dette, d’une part, et le total de l’actif du bilan, d’autre part), est de 1,142 chez les entreprises d’au moins un administrateur représentant des salariés contre 1,271 chez les entreprises n’ayant pas d’administrateurs représentants de salariés.

Conflits d’intérêts

De toute évidence, les actionnaires sont sensibles à la réalisation d’une bonne performance extrafinancière dont ils supportent à eux seuls les coûts s’y rapportant. Cependant, les actionnaires peuvent aussi voir dans la réalisation d’une bonne performance extrafinancière une stratégie pour les dirigeants de s’enraciner en jouant la carte des autres stakeholders, principalement les salariés, dont les intérêts ne coïncident pas nécessairement avec leurs propres intérêts.

Pour les actionnaires, donner des droits de vote aux salariés au sein du conseil d’administration peut donc contrebalancer leur pouvoir, mettant fin à leur suprématie, si relative soit-elle, dans le processus décisionnel.

Partant de l’idée qu’il existe une relation, souvent entretenue par des intérêts communs, entre les dirigeants et les employés, les recherches antérieures mettent en avant le postulat que les dirigeants peuvent procéder à l’augmentation des investissements sociétaux dans un objectif moins louable qui est celui de gagner le soutien et la confiance des salariés pour se soustraire du pouvoir, parfois excessif, des actionnaires.

De surcroît, la réalisation d’un niveau élevé de performance extrafinancière doublée par la nomination des administrateurs salariés dans le conseil d’administration ne peut que renforcer le sentiment de prudence des actionnaires envers les choix stratégiques des dirigeants en matière de développement sociétal.

Les mêmes résultats sont aussi trouvés lorsqu’on considère individuellement les différents piliers de la performance extrafinancière (environnemental, social, et de gouvernance). Nos conclusions confortent l’idée de la présence de conflits d’intérêts majeurs entre les actionnaires et les salariés autour des questions relatives au développement sociétal.

En somme, nos résultats interrogent la façon dont la participation des salariés à la prise de décision est conçue et présentée aux investisseurs financiers. Ces enseignements devraient inciter les entreprises à renforcer leurs efforts de formation et de communication pour plaider en faveur de l’adoption d’un conseil d’administration ouvert aux différentes parties prenantes.

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Normes d'encadrement

Is A Director Resignation Policy Good For Governance?

Ivan Tchotourian 2 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Corporate Board Member fait une intéressante synthèse de la politique de démission d’un administrateur qui ne recevrait pas 50 % des votes lors de son élection : « Is A Director Resignation Policy Good For Governance? » (Matthew Scott). Promeut par les grands investisseurs de ce monde, comment résumer les effets positifs d’une telle politique ? C’est ce que vous propose l’auteur !

Extrait :

While historically such policies have not been strictly enforced, adopting them challenges directors to do what’s right for the organization based on moral considerations and their fiduciary responsibility. Such a policy can also act as an indicator for when board refreshment might be necessary, particularly if support for the entire board begins to fall close to or below the 50 percent threshold.

That shareholders would lobby for this type of policy suggests they are looking for a very direct way to hold board members accountable for the work they do on behalf of the company. This is a growing trend for public companies. Shareholders have reasoned that if a director who is up for re-election to the board and is running unopposed can’t manage to get more than 50 percent of shareholders to vote for their return, then a change is needed. Shareholders aren’t happy that directors who receive less than the majority of votes are allowed to keep their board seats simply because no one ran against them. For corporate boards, the question “Why aren’t shareholders supporting that director?” must be asked, answered and dealt with swiftly. If the largest shareholders aren’t supporting certain board members, it’s only a matter of time before they suggest someone to run against them. It may be better for at-risk directors to resign gracefully before being forced out by a dissident shareholder running a candidate against them.

Additionally, this policy gives affected directors a chance to ask themselves, “Is it the best decision for me to continue to serve on a board where shareholders don’t support my service?” Future career opportunities, reputational impact and board appointments might be at stake.

Having such a resignation policy could have another positive effect on governance – it may make a few more board seats open up faster. Only a limited number of board seats become available each year, so anything that can encourage board turnover in a good way is welcome. This policy could help create more open positions for boards that are looking to add diverse candidates, and at the same time, add new perspectives and innovative thought to board discussions. And most governance professionals would favor that.

À la prochaine…

engagement et activisme actionnarial finance sociale et investissement responsable Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Normes d'encadrement parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

COVID-19, purpose et critères ESG : une alliance nécessaire

Ivan Tchotourian 13 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Billet à découvrir sur le site de Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance pour y lire cet article consacré à la sortie de crise sanitaire et aux apports de la raison d’être et des critères ESG : « ESG and Corporate Purpose in a Disrupted World » (Kristen Sullivan, Amy Silverstein et Leeann Galezio Arthur, 10 août 2020).

Extrait :

Corporate purpose and ESG as tools to reframe pandemic-related disruption

The links between ESG, company strategy, and risk have never been clearer than during the COVID-19 pandemic, when companies have had to quickly pivot and respond to critical risks that previously were not considered likely to occur. The World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Survey 2020, published in January 2020, listed “infectious diseases” as number 10 in terms of potential economic impact, and did not make the top 10 list of risks considered to be “likely.” The impact of the pandemic was further magnified by the disruption it created for the operations of companies and their workforces, which were forced to rethink how and where they did business virtually overnight.

The radical recalibration of risk in the context of a global pandemic further highlights the interrelationships between long-term corporate strategy, the environment, and society. The unlikely scenario of a pandemic causing economic disruption of the magnitude seen today has caused many companies—including companies that have performed well in the pandemic—to reevaluate how they can maintain the long-term sustainability of the enterprise. While the nature and outcomes of that reevaluation will differ based on the unique set of circumstances facing each company, this likely means reframing the company’s role in society and the ways in which it addresses ESG-related challenges, including diversity and inclusion, employee safety, health and well-being, the existence of the physical workplace, supply chain disruptions, and more.

ESG factors are becoming a key determinant of financial strength. Recent research shows that the top 20 percent of ESG-ranked stocks outperformed the US market by over 5 percentage points during a recent period of volatility. Twenty-four out of 26 sustainable index funds outperformed comparable conventional index funds in Q1 2020. In addition, the MSCI ACWI ESG Leaders Index returned 5.24 percent, compared to 4.48 percent for the overall market, since it was established in September 2007 through February 2020. Notably, BlackRock, one of the world’s largest asset managers, recently analyzed the performance of 32 sustainable indices and compared that to their non-sustainable benchmarks as far back as 2015. According to BlackRock the findings indicated that “during market downturns in 2015–16 and 2018, sustainable indices tended to outperform their non-sustainable counterparts.” This trend may be further exacerbated by the effects of the pandemic and the social justice movement.

Financial resilience is certainly not the only benefit. Opportunities for brand differentiation, attraction and retention of top talent, greater innovation, operational efficiency, and an ability to attract capital and increase market valuation are abundant. Companies that have already built ESG strategies, measurements, and high-quality disclosures into their business models are likely to be well-positioned to capitalize on those opportunities and drive long-term value postcrisis.

As businesses begin to reopen and attempt to get back to some sense of normalcy, companies will need to rely on their employees, vendors, and customers to go beyond the respond phase and begin to recover and thrive. In a postpandemic world, this means seeking input from and continuing to build and retain the confidence and trust of those stakeholder groups. Business leaders are recognizing that ESG initiatives, particularly those that prioritize the health and safety of people, will be paramount to recovery.

What are investors and other stakeholders saying?

While current events have forced and will likely continue to force companies to make difficult decisions that may, in the short term, appear to be in conflict with corporate purpose, evidence suggests that as companies emerge from the crisis, they will refresh and recommit to corporate purpose, using it as a compass to focus ESG performance. Specific to the pandemic, the public may expect that companies will continue to play a greater role in helping not only employees, but the nation in general, through such activities as manufacturing personal protective equipment (PPE), equipment needed to treat COVID-19 patients, and retooling factories to produce ventilators, hand sanitizer, masks, and other items needed to address the pandemic. In some cases, decisions may be based upon or consistent with ESG priorities, such as decisions regarding employee health and well-being. From firms extending paid sick leave to all employees, including temporary workers, vendors, and contract workers, to reorienting relief funds to assist vulnerable populations, examples abound of companies demonstrating commitments to people and communities. As companies emerge from crisis mode, many are signaling that they will continue to keep these principles top of mind. This greater role is arguably becoming part of the “corporate social contract” that legitimizes and supports the existence and prosperity of corporations.

In the United States, much of the current focus on corporate purpose and ESG is likely to continue to be driven by investors rather than regulators or legislators in the near term. Thus, it’s important to consider investors’ views, which are still developing in the wake of COVID-19 and other developments.

Investors have indicated that they will assess a company’s response to the pandemic as a measure of stability, resilience ,and adaptability. Many have stated that employee health, well-being, and proactive human capital management are central to business continuity. Investor expectations remain high for companies to lead with purpose, particularly during times of severe economic disruption, and to continue to demonstrate progress against ESG goals.

State Street Global Advisors president and CEO Cyrus Taraporevala, in a March 2020 letter to board members, emphasized that companies should not sacrifice the long-term health and sustainability of the company when responding to the pandemic. According to Taraporevala, State Street continues “to believe that material ESG issues must be part of the bigger picture and clearly articulated as part of your company’s overall business strategy.” According to a recent BlackRock report, “companies with strong profiles on material sustainability issues have potential to outperform those with poor profiles. We believe companies managed with a focus on sustainability may be better positioned versus their less sustainable peers to weather adverse conditions while still benefiting from positive market environments.”

In addition to COVID-19, the recent social justice movement compels companies to think holistically about their purpose and role in society. Recent widespread protests of systemic, societal inequality leading to civil unrest and instability elevate the conversation on the “S” and “G” in ESG. Commitments to the health and well-being of employees, customers, communities, and other stakeholder groups will also require corporate leaders to address how the company articulates its purpose and ESG objectives through actions that proactively address racism and discrimination in the workplace and the communities where they operate. Companies are responding with, among other things, statements of support for diversity and inclusion efforts, reflective conversations with employees and customers, and monetary donations for diversity-focused initiatives. However, investors and others who are pledging to use their influence to hold companies accountable for meaningful progress on systemic inequality will likely look for data on hiring practices, pay equity, and diversity in executive management and on the board as metrics for further engagement on this issue.

What can boards do?

Deloitte US executive chair of the board, Janet Foutty, recently described the board as “the vehicle to hold an organization to its societal purpose.” Directors play a pivotal role in guiding

companies to balance short-term decisions with long-term strategy and thus must weigh the needs of all stakeholders while remaining cognizant of the risks associated with each decision. COVID-19 has underscored the role of ESG principles as central to business risk and strategy, as well as building credibility and trust with investors and the public at large. Boards can advise management on making clear, stakeholder-informed decisions that position the organization to emerge faster and stronger from a crisis.

It has been said before that those companies that do not control their own ESG strategies and narratives risk someone else controlling their ESG story. This is particularly true with regards to how an organization articulates its purpose and stays grounded in that purpose and ESG principles during a crisis. Transparent, high-quality ESG disclosure can be a tool to provide investors with information to efficiently allocate capital for long-term return. Boards have a role in the oversight of both the articulation of the company’s purpose and how those principles are integrated with strategy and risk.

As ESG moves to the top of the board agenda, it is important for boards to have the conversation on how they define the governance structure they will put in place to oversee ESG. Based on a recent review, completed by Deloitte’s Center for Board Effectiveness, of 310 company proxies in the S&P 500, filed from September 1, 2019, through May 6, 2020, 57 percent of the 310 companies noted that the nominating or governance committee has primary oversight responsibility, and only 9 percent noted the full board, with the remaining 34 percent spread across other committees. Regardless of the primary owner, the audit committee should be engaged with regard to any ESG disclosures, as well as prepared to oversee assurance associated with ESG metrics.

Conclusion

The board’s role necessitates oversight of corporate purpose and how corporate purpose is executed through ESG. Although companies will face tough decisions, proactive oversight of and transparency around ESG can help companies emerge from recent events with greater resilience and increased credibility. Those that have already embarked on this journey and stay the course will likely be those well-positioned to thrive in the future.

Questions for the board to consider asking:

How are the company’s corporate purpose and ESG objectives integrated with strategy and risk?

- Has management provided key information and assumptions about how ESG is addressed during the strategic planning process?

- How is the company communicating its purpose and ESG objectives to its stakeholders?

- What data does the company collect to assess the impact of ESG performance on economic performance, how does this data inform internal management decision- making, and how is the board made aware of and involved from a governance perspective?

- Does the company’s governance structure facilitate effective oversight of the company’s ESG matters?

- How is the company remaining true to its purpose and ESG, especially now given COVID-19 pandemic and social justice issues?

- What is the board’s diversity profile? Does the board incorporate diversity when searching for new candidates?

- Have the board and management discussed executive management succession and how the company can build a diverse pipeline of candidates?

- How will the company continue to refresh and recommit to its corporate purpose and ESG objectives as it emerges from the pandemic response and recovery and commit to accelerating diversity and inclusion efforts?

- How does the company align its performance incentives for executive leadership with attaining critical ESG goals and outcomes?

À la prochaine…

devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Normes d'encadrement normes de droit normes de marché Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Étude de l’UE sur les devoirs des administrateurs : une gouvernance loin d’être durable !

Ivan Tchotourian 12 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Belle étude qu’offre l’Union européenne sur les devoirs des administrateurs et la perspective de long-terme : « Study on directors’ duties and sustainable corporate governance » (29 juillet 2020). Ce rapport document le court-termisme de la gestion des entreprises en Europe. En lisant les grandes lignes de ce rapport, on se rend compte d’une chose : on est loin du compte et la RSE n’est pas encore suffisamment concrétisée…

Résumé :

L’accent mis par les instances décisionnelles au sein des entreprises sur la maximisation à court terme du profit réalisé par les parties prenantes, au détriment de l’intérêt à long terme de l’entreprise, porte atteinte, à long terme, à la durabilité des entreprises européennes, tant sous l’angle économique, qu’environnemental et social.

L’objectif de cette étude est d’évaluer les causes du « court-termisme » dans la gouvernance d’entreprise, qu’elles aient trait aux actuelles pratiques de marché et/ou à des dispositions réglementaires, et d’identifier d’éventuelles solutions au niveau de l’UE, notamment en vue de contribuer à la réalisation des Objectifs de Développement Durable fixés par l’Organisation des Nations Unies et des objectifs de l’accord de Paris en matière de changement climatique.

L’étude porte principalement sur les problématiques participant au « court-termisme » en matière de droit des sociétés et de gouvernance d’entreprises, lesquelles problématiques ayant été catégorisées autour de sept facteurs, recouvrant des aspects tels que les devoirs des administrateurs et leur application, la rémunération et la composition du Conseil d’administration, la durabilité dans la stratégie d’entreprise et l’implication des parties prenantes.

L’étude suggère qu’une éventuelle action future de l’UE dans le domaine du droit des sociétés et de gouvernance d’entreprise devrait poursuivre l’objectif général de favoriser une gouvernance d’entreprise plus durable et de contribuer à une plus grande responsabilisation des entreprises en matière de création de valeur durable. C’est pourquoi, pour chaque facteur, des options alternatives, caractérisées par un niveau croissant d’intervention réglementaire, ont été évaluées par rapport au scénario de base (pas de changement de politique).

Pour un commentaire, voir ce billet du Board Agenda : « EU urges firms to focus on long-term strategy over short-term goals » (3 août 2020).

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Normes d'encadrement

Repenser la gouvernance : 3 pistes pour le CA

Ivan Tchotourian 29 juillet 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Douglas Chia dans Corporate Board Member offre une belle lecture sur les trois voies autour desquelles le CA pourrait penser la gouvernance d,entreprise de demain : « Three Ways for Boards to Rethink Governance ».

Extrait :

1. The Board’s Role: Rethink what the board is there to do.

Everyone agrees that the role of the board has changed over the past two decades, not from the perspective of a director’s fiduciary duties, but rather through stakeholders with increased expectations for what the board is there to do and lower tolerance for underperformance from their perspectives. For many boards, the ground that represents their role has noticeably shifted under their feet. But, when was the last time the board met in executive session for the express purpose of thinking about how the company’s stakeholders look at the board’s role and what that particular company needs from its board? Most annual board self-evaluations are brief sessions for the independent directors to ask each other “How do we think we’re doing?” without deeper thought about what it is they need to be doing to best serve that company.

Boards should set aside time to rethink their role in the context of the fundamental changes their companies will be facing going forward. A board can do this by taking its self-evaluation to the next level and by revisiting its charter, mission statement or governance principles as an exercise in rethinking its purpose. As companies face a new world order, it is more important than ever for the entire board to be on the same page for what it is there to do.

2. The Board’s Committees: Rethink whether the board’s committee structure is stakeholder-driven.

The tide of companies turning away from shareholder primacy and committing (or recommitting) to the stakeholder model of governance creates the conditions for boards to step back and look at how they allocate their attention to the interests of each of the commonly-thought-of key stakeholders: customers, employees, communities and shareholders. A board typically handles its agenda by covering high-level concerns at the full board level and delegating to its standing committees those subjects of particular importance to the company requiring more specific and deeper dives.

Currently, the committees prescribed by law are audit, compensation and nominating. These three committees are largely designed look after the direct interests of the shareholders. So, where do the direct interests of the other three stakeholders get covered? If the answer is “at the full board level,” it may be time to rethink whether that still works and if certain interests of stakeholders other than shareholders should receive deeper-dive treatment in committee. The board can do this by mapping each of the items it covers—both at the full board and in committees—to one or more of the four stakeholders. Upon doing this, it may become apparent that the allocation of the board’s time is out of balance, and the customers, employees, and communities could use more attention at the committee level.

This may mean adjusting or redesigning the structure and scope of the board’s committees. Some boards already have standing committees to cover subjects that relate more directly to its customers (e.g., risk, product safety, innovation) and communities (e.g., public policy). Recently, there have been calls for boards to “reimagine” the scope of their compensation committees to cover the company’s overall workforce and issues of human capital going far beyond executive compensation and benefits. It may be time for boards go even further to rethink whether its governance is truly stakeholder-driven and reimagine how to restructure its agenda and committees to understand and balance the interests of the corporation’s four key stakeholders.

3. The Board’s Resources: Rethink whether the board is sufficiently resourced versus sufficiently paid.

Before March 2020, director compensation had been on a steady, upward trend on the notion that directors are being asked to spend more and more time on their board duties and should be paid commensurate with the amount of work. During the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to cutting the pay of the CEO and other executives, many boards have temporarily reduced director compensation, not so much hold down costs, but to show employees that the people with ultimate accountability are willing to impose real sacrifices on themselves. If the assumption is that director compensation will go back up to its original levels once business goes “back to normal,” boards need to rethink that.

Boards have felt the pile-on effect of stakeholders continually expecting them to oversee additional areas of concern and own them in a bigger way: political spending, climate change, cybersecurity, data privacy, human capital, artificial intelligence and now pandemic preparedness, just to name a few. Like with all individuals, while a director can be compensated for increased amounts of work, his or her capacity to do a good job will eventually reach its limit, regardless of how much you pay them. What they need are additional resources.

À la prochaine…

devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration objectifs de l'entreprise Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

CA : faire ce qui est juste

Ivan Tchotourian 14 juillet 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Intéressante tribune dans La presse par Milville Tremblay : « Faire ce qui est juste » (14 juillet 2020). Cela semble une évidence mais il est bon de le rappeler !

Extrait :

Faire ce qui est juste, c’est placer la barre plus haut que la légalité des décisions et la satisfaction des seuls actionnaires. Même dans l’adversité, on s’attend aujourd’hui à ce que les dirigeants tiennent compte des besoins légitimes de toutes les parties prenantes de l’entreprise : les employés, les clients, les fournisseurs, les gouvernements, la société en général, l’environnement et, bien sûr, les actionnaires.

(…) Considérer ne veut pas dire donner raison à tous ou nuire à personne. Une compagnie n’est pas l’État-providence. Parfois les dirigeants doivent prendre des décisions qui font mal, mais beaucoup dépend de la manière.

L’opinion publique juge sévèrement ceux qui exigent des sacrifices de tous — sans toucher à leurs propres privilèges, comme on l’a vu chez Bombardier.

(…) Le tribunal de l’opinion publique tranche vite et sans appel. La bonne réputation d’une entreprise prend des années à bâtir et se brise en un instant. Non seulement les dirigeants doivent-ils prendre des décisions justes, mais aussi savoir communiquer avec franchise, surtout s’il y a eu faute. Ceux qui espèrent que leurs bourdes passeront inaperçues courent un risque élevé.

Les bailleurs de fonds exercent aussi une pression accrue sur les patrons. Un nombre croissant de grands gestionnaires d’actifs intègrent les dimensions ESG (pour environnement, social et gouvernance) dans la sélection des sociétés en portefeuille. Les grandes caisses de retraite publiques canadiennes, telle la Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec, sont du nombre. Ces gestionnaires de fonds commencent à retirer leur appui aux dirigeants qui s’entêtent dans l’erreur et aux administrateurs qui les tolèrent, leur adressent des remontrances derrière les portes closes ou préfèrent les actions d’un concurrent, qui fait ce qui est juste.

(…) On s’attend aujourd’hui à ce que les dirigeants saisissent rapidement les changements de valeurs portés par l’air du temps, ce qui n’est pas évident pour ceux qui s’isolent avec des gens qui pensent comme eux. Il est trop tard, s’ils attendent de réagir à ce qui est devenu évident.

En matière de gouvernance, on regrette les trop lents progrès pour faire place aux femmes à la haute direction et dans les conseils d’administration.

Et si on décante le mouvement Black Lives Matters, on réalise que la diversité ne se limite pas au sexe. Il ne s’agit pas seulement d’une question d’équité, mais d’intégrer des perspectives variées pour de meilleures décisions.

Le profit n’est plus une finalité, mais une exigence pour assurer la croissance à long terme de l’entreprise. Sans profit, les sources de capital se tarissent et avec elles la capacité d’investir et d’innover.

Mais au-delà des profits, les dirigeants doivent réfléchir à l’utilité sociale de leur entreprise, comme le recommande la Business Roundtable, une association de PDG américains. Le piège, comme d’autres modes en management, est qu’il n’en résultera qu’un slogan, que les employés découvriront creux.

Le regard des employés est souvent plus cynique que celui du public, car ils sont mieux placés pour déceler les écarts entre le discours et la réalité. Les dirigeants qui posent des gestes cohérents et qui reconnaissent les inévitables manquements ont de meilleures chances de mobiliser leurs troupes. Les travailleurs du savoir, particulièrement les milléniaux, ne s’achètent plus avec un bon salaire et une table de billard. Ils veulent aussi que l’entreprise reflète leurs valeurs.

La crise braque les projecteurs sur la manière dont la gouvernance traite la dimension sociale de l’entreprise, soit les lettres G et S des critères ESG. La préoccupation pour le E de l’environnement n’a pas disparu et j’y reviendrai prochainement.

En effet, la plupart des patrons ont posé des gestes énergiques pour protéger la santé de leurs employés et de leurs clients. Quelques-uns se sont lancés dans la production de matériel de protection sanitaire. Plusieurs ont sabré leur salaire à l’annonce de mises à pied, bien que certains vont se refaire avec de nouvelles options d’achat d’actions à prix déprimé.

Les exemples d’entreprises sur la sellette se multiplient. Facebook fait face au boycottage de grands annonceurs pour n’avoir pas éradiqué les discours haineux de sa plateforme. Adidas est durement critiquée pour étrangler ses fournisseurs. Amazon, dénoncée pour négliger la santé de ses travailleurs durant la pandémie. Plus près de nous, Ubisoft clouée au pilori pour avoir fermé les yeux sur le harcèlement de ses employées. Pas besoin d’être devin pour anticiper les critiques des sociétés qui auront bénéficié de l’aide publique tout en recourant aux paradis fiscaux.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration parties prenantes Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Du shareholder au stakeholder

Ivan Tchotourian 14 juillet 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Sébastien Thevoux Chabuel propos un article intéressant dans la revue Banque (15 mai 2020): « Du shareholder au stakeholder : comment organiser le gouvernement d’entreprise ? ». Une belle lecture…

Extrait :

La question de la responsabilité ne se pose jamais aussi bien qu’en période de crise et d’incertitude. En effet, qu’elle soit intense et courte – comme celles de 2008 et de la COVID-19 – ou larvée et longue – comme la crise climatique –, chaque crise agit comme un test sur la solidité du système et la responsabilité des acteurs, et interpelle sur les éventuelles solutions à mettre en place. Dans un monde hyperfinanciarisé où l’actionnaire occupe un rôle central dans le fonctionnement de l’entreprise, il paraît légitime de vouloir reconfigurer les règles du jeu et donner plus d’importance aux…

À la prochaine…