devoirs des administrateurs engagement et activisme actionnarial Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration normes de droit objectifs de l'entreprise Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Le rendement à court-terme, une menace pour nos entreprises

Ivan Tchotourian 14 mars 2017

Bel article du Journal de Montréal : « Le rendement à court-terme, une menace pour nos entreprises » (22 novembre 2016). Une occasion de discuter gouvernance d’entreprise en se concentrant sur la situation actuelle caractérisée par une omniprésence des investisseurs institutionnels !

Auparavant, les petits investisseurs québécois conservaient leurs actions en bourse en moyenne 10 ans. Aujourd’hui, à peine quatre mois. Quelque chose a changé dans notre rapport aux entreprises. Et pas pour le mieux, dit Gaétan Morin, président et chef de la direction du Fonds de solidarité FTQ.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance objectifs de l'entreprise Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Maximisation de la valeur actionnariale : une belle critique

Ivan Tchotourian 6 février 2017

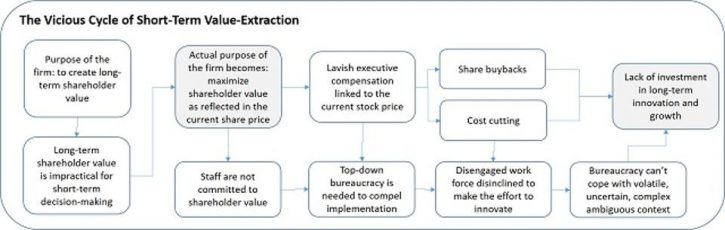

Bonsoir à toutes et à tous, dans « Resisting The Lure Of Short-Termism: Kill ‘The World’s Dumbest Idea' » publié dans Forbes, Steve Denning revient sur une belle critique de la maximisation de la valeur actionnariale comme objectif des entreprises.

When pressures are mounting to deliver short-term results, how do successful CEOs resist those pressures and achieve long-term growth? The issue is pressing: low global economic growth is putting stress on the political and social fabric in Europe and the Americas and populist leaders are mobilizing widespread unrest. “By succumbing to false solutions, born of disillusion and rage,” writes Martin Wolf in the Financial Times this week, “the west might even destroy the intellectual and institutional pillars on which the postwar global economic and political order has rested.”

The first step in resisting the pressures of short-termism is to correctly identify their source. The root cause is remarkably simple—the view, which is widely held both inside and outside the firm, that the very purpose of a corporation is to maximize shareholder value as reflected in the current stock price (MSV). This notion, which even Jack Welch has called “the dumbest idea in the world,” got going in the 1980s, particularly in the U.S., and is now regarded in much of the business world, the stock market and government as an almost-immutable truth of the universe. As The Economist even declared in March 2016, MSV is now “the biggest idea in business.”

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

Gouvernance normes de droit Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

5 mythes sur la gouvernance d’entreprise – 1re partie

Ivan Tchotourian 26 janvier 2017

« 5 mythes sur la gouvernance d’entreprise (1re partie) » est mon dernier de blogue sur Contact. À cette occasion, je repense certains facteurs économiques fondamentaux de la gouvernance d’entreprise. Ces facteurs s’appuient sur une série de présupposés issus des sciences économiques, financières, de la gestion et juridiques. Ces présupposés sont ancrés dans une culture anglo-américaine, mais ils ont largement été véhiculés dans le monde. Ils relèvent à mon sens d’une mythologie qu’il est temps de dénoncer.

Voici les 5 présupposés autour desquels s’articule cette mythologie:

1. La société par actions est un simple contrat.

2. Les actionnaires sont les propriétaires de la société par actions.

3. Les actionnaires sont les seuls créanciers résiduels.

4. Les actionnaires dotés de nouveaux pouvoirs s’investissent activement et positivement dans la gouvernance.

5. L’objectif de la gouvernance d’entreprise est de satisfaire l’intérêt des actionnaires.

Je reviens sur chacun de ces présupposés pour démontrer qu’ils appartiennent à une mythologie qui ne saurait justifier une remise en question du mouvement grandissant de responsabilisation des entreprises.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Court-termisme : les propositions de The Aspen Institute

Ivan Tchotourian 2 janvier 2017

The Aspen Institute (par l’intermédiaire de The American Prosperity Project Working Group) vient de publier un rapport proposant de contrer le court-termisme qui gangrène les entreprises américaines. Dans « The American Prosperity Project: Policy Framework », le groupe de travail propose 3 pistes de solutions qui sont les suivantes :

- Focus government investment on recognized drivers of long-term productivity growth and global competitiveness—namely, infrastructure, basic science research, private R&D, and skills training—in order to close the decades-long investment shortfall in America’s future. Building this foundation will support good jobs and new business formation, support workers affected by globalization and technology, and better position America to address the national debt through long-term economic growth.

- Unlock business investment by modernizing our corporate tax system to achieve one that is simpler, fair to businesses across the spectrum of size and industry, and supportive of both productivity growth and job creation. Changes to the corporate tax system could reduce the federal corporate statutory tax rate (at 35%, the highest in the world), broaden the base of corporate tax payers, bring off-shore capital back to the US, and reward long-term investment, and help provide revenues to assure that America’s long-term goals can be met.

- Align public policy and corporate governance protocols to facilitate companies’ and investors’ focus on long-term investment. Complex layers of market pressures, governance regulations, and business norms encourage short-term thinking in business and finance. The goal is a better environment for long-term investing by business leaders and investors, and to provide better outcomes for society.

Pour une synthèse de ce rapport de travail, vous pourrez lire cet excellent article d’Alana Semuels dans The Atlantic « How to Stop Short-Term Thinking at America’s Companies » (30 décembre 2016).

There was a time, half a century ago, when what was good for many American corporations tended to also be good for America. Companies invested in their workers and new technologies, and as a result, they prospered and their employees did too.

Now, a growing group of business leaders is worried that companies are too concerned with short-term profits, focused only on making money for shareholders. As a result, they’re not investing in their workers, in research, or in technology—short-term costs that would reduce profits temporarily. And this, the business leaders say, may be creating long-term problems for the nation.

“Too many CEOs play the quarterly game and manage their businesses accordingly,” Paul Polman, the CEO of the British-Dutch conglomerate Unilever, told me. “But many of the world’s challenges can not be addressed with a quarterly mindset.”

Polman is one of a group of CEOs and business leaders that have signed onto the American Prosperity Project, an initiative spearheaded by the Aspen Institute, to encourage companies and the nation to engage in more long-term thinking. The group, which includes CEOs such as Chip Bergh of Levi Strauss and Ian Read of Pfizer, board directors such as Janet Hill of Wendy’s and Stanley Bergman of Henry Schein, Inc., and labor leaders such as Damon Silvers of the AFL-CIO, have issued a report encouraging the government to make it easier for companies to think in the long-term by investing in infrastructure and changing both the tax code and corporate governance laws.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

Gouvernance normes de droit Nouvelles diverses Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Enron : 15 ans déjà

Ivan Tchotourian 8 décembre 2016

Dans « Why Enron Remains Relevant » (Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance and Financial Regulation, 2 décembre 2016), Michael W. Peregrine aborde les leçons de l’affaire Enron, 15 ans après. Un bel article !

The fifteenth anniversary of the Enron bankruptcy (December 2, 2001) provides an excellent opportunity for the general counsel to review with a new generation of corporate officers and directors the problematic board conduct that proved to have seismic and lasting implications for corporate governance. The self-identified failures of Enron director oversight not only led to what was at the time the largest bankruptcy in U.S. history, but also served as a leading prompt for the enactment of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act, and the corporate responsibility movement that followed. For those reasons, the Enron bankruptcy remains one of the most consequential governance developments in corporate history.

Enron evolved from a natural gas company to what was by 2001 a highly diversified energy trading enterprise that pursued various forms of particularly complex transactions. Among these were the soon-to-be notorious related party transactions in which Enron financial management executives held lucrative economic interests. (These were the so-called “Star Wars” joint ventures, with names such as “Jedi”, “Raptor” and “Chewco”). Not only was Enron’s management team experienced, both its board and its audit committee were composed of individuals with broad and diverse business, accounting and regulatory backgrounds.

In the late 1990s the company experienced rapid growth, such that by March 2001 its stock was trading at 55 times earnings. However, that rapid growth attracted substantial scrutiny, including reports in the financial press that seriously questioned whether such high value could be sustained. These reports focused in part on the complexity and opaqueness of the company’s financial statements, that made it difficult to accurately track its source of income.

By mid-summer 2001 its share price began to drop; CEO Jeff Skilling unexpectedly resigned in August; the now-famous Sherron Watkins whistleblower letter was sent (anonymously) to Board Chair Ken Lay on August 15. On October 16, the company announced its intention to restate its financial statements from 1997 to 2007. On October 21 the SEC announced that it had commenced an investigation of the related party transactions. Chief Financial Officer Andrew Fastow was fired on October 25 after disclosing to the board that he had earned $30 million from those transactions. On October 29, Enron’s credit rating was lowered. A possible purchaser of Enron terminated negotiations on November 28, and the company filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection on December 2.

The rest became history: the collapse of the company; the individual criminal prosecutions and convictions; the obstruction of justice verdict against company and, for Arthur Andersen (subsequently but belatedly overturned); the loss of scores of jobs and the collateral damage to the city of Houston; Mr. Lay’s sudden death; and, ultimately the 2002 enactment of the Sarbanes Oxley Act, which was intended to prevent future accounting, financial and governance failings as had occurred in Enron and other similar corporate scandals. But a 2016 Enron board briefing would be much more than a financial history lesson. For the continuing relevance of Enron is at least two-fold

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration objectifs de l'entreprise Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Les actionnaires ne sont pas les propriétaires de l’entreprise !

Ivan Tchotourian 13 novembre 2016

L’Afrique du Sud l’affirme et l’assume : la primauté actionnariale doit être remise en cause et la gouvernance d’entreprise doit s’ouvrir aux parties prenantes. Dans son dernier rapport de novembre 2016 (King IV Report on Corporate Governance), l’institut des administrateurs de sociétés sud-africaines ne dit pas autre chose !

Vous pourrez lire l’intéressante synthèse suivante : « King: Shareholders not owners of companies » (10 novembre 2016, Fin24 city press).

Shareholders are not the owners of a company – they are just one of the stakeholders, Prof Mervyn King said on Thursday at the 15th BEN-Africa Conference, which took place in Stellenbosch.

« I realised long ago that the primacy of shareholders could not be the basis in the rainbow nation, » said King. The corporate governance theory of shareholder primacy holds that shareholder interests should have first priority relative to all other corporate stakeholders.

He said when he started with his report on corporate governance the issue was that the majority of SA’s citizens were not in the mainstream of the economy. His guidelines on corporate governance, therefore, had to be for people who had never been in that mainstream of society.

The King Reports on Corporate Governance are regarded as ground-breaking guidelines for the governance structures and operation of companies in SA. The first was issued in 1994, the second in 2002, the third in 2009 and the fourth revision was released last week.

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian

devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses objectifs de l'entreprise Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

Retour sur le devoir fiduciaire : une excuse pour maximiser le retour des actionnaires ?

Ivan Tchotourian 24 octobre 2016

Intéressant ce que relaie le Time. Il y a un des candidats à l’élection présidentielle américaine a invoqué le devoir fiduciaire pour justifier les politiques d’évitement fiscales qu’il a mises en œuvre pendant de nombreuses années : « Donald Trump’s ‘Fiduciary Duty’ Excuse on Taxes Is Just Plain Wrong ». Qu’en penser ? Pour la journaliste Rana Foroohar, la réponse est claire : « The Donald and his surrogates say he has a legal responsibility to minimize tax payments for his shareholders. It’s not a good excuse ».

It’s hard to know what to say to the New York Times’ revelation that Donald Trump lost so much money running various casino and hotel businesses into the ground in the mid-1990s ($916 million to be exact) that he could have avoided paying taxes for a full 18 years as a result (which may account for why he hasn’t voluntarily released his returns—they would make him look like a failure).

But predictably, Trump did have a response – fiduciary duty made me do it. So, how does the excuse stack up? Does Donald Trump, or any taxpayer, have a “fiduciary duty,” or legal responsibility, to maximize his income or minimize his payments on his personal taxes? In a word, no. “His argument is legal nonsense,” says Cornell University corporate and business law professor Lynn Stout,

À la prochaine…

Ivan Tchotourian