actualités internationales Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Gouvernance normes de droit

Les adieux au reporting extra-financier… vraiment ?

Ivan Tchotourian 29 avril 2021 Ivan Tchotourian

Blogging for sustainability offre un beau billet sur la construction européenne du reporting extra-financier : « Goodbye, non-financial reporting! A first look at the EU proposal for corporate sustainability reporting » (David Monciardini et Jukka Mähönen, 26 April 2021). Les auteurs soulignent la dernière position de l’Union européenne (celle du 21 avril 2021 qui modifie le cadre réglementaire du reporting extra-financier) et explique pourquoi celle-ci est pertinente. Du mieux certes, mais encore des critiques !

Extrait :

A breakthrough in the long struggle for corporate accountability?

Compared to the NFRD, the new proposal contains several positive developments.

First, the concept of ‘non-financial reporting’, a misnomer that was widely criticised as obscure, meaningless or even misleading, has been abandoned. Finally we can talk about mandatory sustainability reporting, as it should be.

Second, the Commission is introducing sustainability reporting standards, as a common European framework to ensure comparable information. This is a major breakthrough compared to the NFRD that took a generic and principle-based approach. The proposal requires to develop both generic and sector specific mandatory sustainability reporting standards. However, the devil is in the details. The Commission foresees that the development of the new corporate sustainability standards will be undertaken by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), a private organisation dominated by the large accounting firms and industry associations. As we discuss below, the most important issue is to prevent the risks of regulatory capture and privatization of EU norms. What is a step forward, though, is the companies’ duty to report on plans to ensure the compatibility of their business models and strategies with the transition towards a zero-emissions economy in line with the Paris Agreement.

Third, the scope of the proposed CSRD is extended to include ‘all large companies’, not only ‘public interest entities’ (listed companies, banks, and insurance companies). According to the Commission, companies covered by the rules would more than triple from 11,000 to around 49,000. However, only listed small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are included in the proposal. This is a major flaw in the proposal as the negative social and environmental impacts of some SMEs’ activities can be very substantial. Large subsidiaries are thereby excluded from the scope, which also is a major weakness. Besides, instead of scaling the general standards to the complexity and size of all undertakings, the Commission proposes a two-tier regime, running the risk of creating a ‘double standard’ that is less stringent for SMEs.

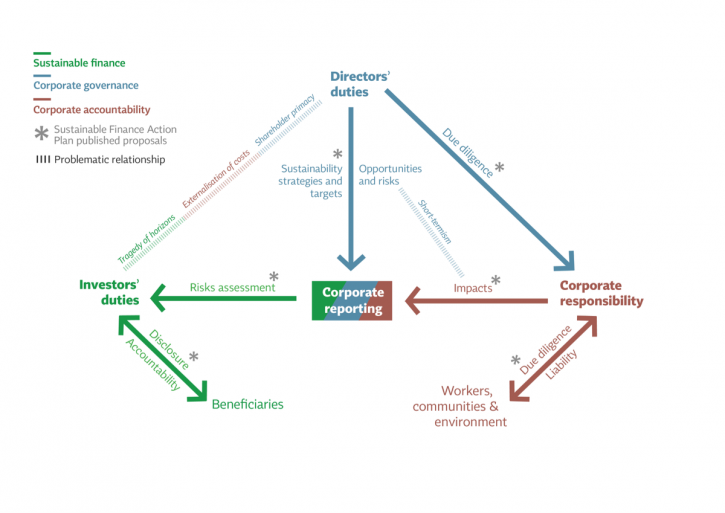

Fourth, of the most welcomed proposals, however, is strengthening a ‘double materiality’ principle for standards (making it ‘enshrined’, according to the Commission), to cover not only just the risks of unsustainability to companies themselves but also the impacts of companies on society and the environment. Similarly, it is positive that the Commission maintains a multi-stakeholder approach, whereas some of the international initiatives in place privilege the information needs of capital providers over other stakeholders (e.g. IIRC; CDP; and more recently the IFRS).

Fifth, a step forward is the compulsory digitalisation of corporate disclosure whereby information is ‘tagged’ according to a categorisation system that will facilitate a wider access to data.

Finally, the proposal introduces for the first time a general EU-wide audit requirement for reported sustainability information, to ensure it is accurate and reliable. However, the proposal is watered down by the introduction of a ‘limited’ assurance requirement instead of a ‘reasonable’ assurance requirement set to full audit. According to the Commission, full audit would require specific sustainability assurance standards they have not yet planned for. The Commission proposes also that the Member States allow firms other than auditors of financial information to assure sustainability information, without standardised assurance processes. Instead, the Commission could have follow on the successful experience of environmental audit schemes, such as EMAS, that employ specifically trained verifiers.

No time for another corporate reporting façade

As others have pointed out, the proposal is a long-overdue step in the right direction. Yet, the draft also has shortcomings, which will need to be remedied if genuine progress is to be made.

In terms of standard-setting governance, the draft directive specifies that standards should be developed through a multi-stakeholder process. However, we believe that such a process requires more than symbolic trade union and civil society involvement. EFRAG shall have its own dedicated budget and staff so to ensure adequate capacity to conduct independent research. Similarly, given the differences between sustainability and financial reporting standards, EFRAG shall permanently incorporate a balanced representation of trade unions, investors, civil society and companies and their organisations, in line with a multi-stakeholder approach.

The proposal is ambiguous in relation to the role of private market-driven initiatives and interest groups. It is crucial that the standards are aligned to the sustainability principles that are written in the EU Treaties and informed by a comprehensive science-based understanding of sustainability. The announcement in January 2020 of the development of EU sustainability reporting standards has been followed by the sudden move by international accounting body the IFRS Foundation to create a global standard setting structure, focusing only on financially material climate-related disclosures. In the months to come, we can expect enormous pressure on EU policy-makers to adopt this privatised and narrower approach, widely criticised by the academic community.

Furthermore, the proposal still represents silo thinking, separating sustainability disclosure from the need to review and reform financial accounting rules (that remain untouched). It still emphasises transparency over governance. Albeit it includes a requirement for companies to report on sustainability due diligence and actual and potential adverse impacts connected with the company’s value chain, it lacks policy coherence. The proposal’s link with DG Justice upcoming legislation on the boards’ sustainability due diligence duties later this year is still tenuous.

After decades of struggles for mandatory high-quality corporate sustainability disclosure, we cannot afford another corporate reporting façade. It is time for real progress towards corporate accountability.

À la prochaine…

Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Nouvelles diverses

La matérialité au cœur du reporting extra-financier

5 décembre 2018 Loïc Geelhand de Merxem

La matérialité au cœur du reporting extra-financier

Le cabinet Tennaxia a publié très récemment un livre blanc[1] à destination des entreprises sur la manière de réaliser une analyse de matérialité. C’est l’occasion de s’intéresser à cette notion, assez nouvelle en France, mais pourtant déjà très présente en Amérique du Nord ou dans les référentiels internationaux de reporting extra-financier.

Qu’est-ce que la matérialité ?

De prime abord, il est important de préciser qu’il n’existe pas de définition claire et précise de la matérialité. Très concrètement, il s’agit de la pertinence de l’information divulguée. Lorsque l’entreprise communique, elle doit communiquer de l’information « matérielle », c’est-à-dire pertinente.

Le livre blanc propose une définition consensuelle et plus complète de la matérialité :

« La matérialité recouvre tous les aspects économiques, environnementaux, sociaux et sociétaux qui sont susceptibles d’impacter la stratégie, le modèle d’affaire de l’entreprise ainsi que sa performance durable et d’impacter, de manière substantielle, ses parties prenantes, au premier rang desquelles les investisseurs, ainsi que sur l’appréciation qu’elles portent sur l’entreprise »[2].

Cette matérialité devient extrêmement importante lors de la divulgation extra-financière. À l’image de l’information financière, la matérialité devient le critère à la base même de cette transparence puisque c’est par ce biais que l’information va être divulguée ou non.

Pourquoi parle-t-on de matérialité dans le cadre d’un reporting extra-financier ?

La divulgation extra-financière se résume brièvement pour une entreprise ou un investisseur, de communiquer de l’information quant à ses enjeux environnementaux, sociaux et de gouvernance. Le reporting devient un véritable vecteur de transparence.

Cependant, avant de pouvoir communiquer sur ces données extra-financières, l’entreprise ou l’investisseur doit faire un travail d’introspection : elle doit voir ses faiblesses, ses forces et déterminer très précisément ses véritables enjeux.

C’est à ce moment que la « matrice de matérialité » entre en jeu. La matérialité devient alors l’examen où l’entreprise choisit ses enjeux qui sont à la fois internes (en termes de business), mais aussi externes, c’est-à-dire envers les parties prenantes[3]. Par exemple, le gaspillage alimentaire est pertinent et matériel pour une entreprise dans la grande distribution. Il ne l’est pas pour une entreprise de location de baux commerciaux.

La matérialité fait son apparition en France

Il est intéressant de noter que la France, champion en termes de reporting extra-financier, n’a que très récemment intégré ce principe de matérialité[4].

Le changement de philosophie s’opère vers « une culture de la pertinence là où le droit antérieur recherchait l’exactitude des informations de nature sociétale »[5]. Pour certains, « la nouvelle orientation vers une analyse de la matérialité devrait inciter les entreprises à utiliser leur politique RSE comme un outil pertinent au service de la performance globale par une meilleure intégration de ces considérations dans les décisions stratégiques »[6]. Il n’est plus question de divulguer passivement de l’information, mais de divulguer de l’information pertinente et appropriée[7].

Il n’existe pas de définition de la matérialité dans la loi. La principale organisation patronale représentant les entreprises françaises, le MEDEF, confirme dans son guide sur le reporting extra-financier le principe de matérialité[8]. Cette analyse de matérialité s’apparente en réalité à une analyse des risques extra-financiers

La matérialité en Amérique du Nord

On retrouve déjà ce principe de materiality dans les pays d’Amérique du Nord. Ce principe qui s’intéressait surtout aux états financiers a été étendu aux données extra-financières.

Au Canada, en ce qui concerne l’information environnementale, le critère essentiel à la divulgation de ces informations se base sur l’information pertinente. C’est ce facteur qui doit être pris « en compte dans l’appréciation des éléments d’information à communiquer[9] ». Dans son avis, l’autorité explique le processus à suivre afin de savoir si une information est considérée comme importante ou non. Elle le résume brièvement, à savoir si la question environnementale considérée est importante, notamment pour l’investisseur et s’il faut communiquer de l’information à ce sujet.

Aux États-Unis, les grandes entreprises se soumettent à la Sustainability accounting standards board (« SASB ») lorsqu’elle divulgue de l’information extra-financière. Cette entité privée a pour but de créer des standards comptables afin de promouvoir la divulgation extra-financière en fonction des secteurs et industries. Elle travaille notamment à intégrer ses référentiels dans les documents annuels à soumettre à la Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC)[10]. La définition retenue par le SASB est la définition de la Cour Suprême des États-Unis[11] dans l’affaire TSC Indus. v. Northway, Inc.[12] :

« According to the U.S. Supreme Court, a fact is material if, in the event such fact is omitted from a particular disclosure, there is “a substantial likelihood that the disclosure of the omitted fact would have been viewed by the reasonable investor as having significantly altered the ‘total mix’ of the information made available ».

La diversité des définitions dans les référentiels internationaux

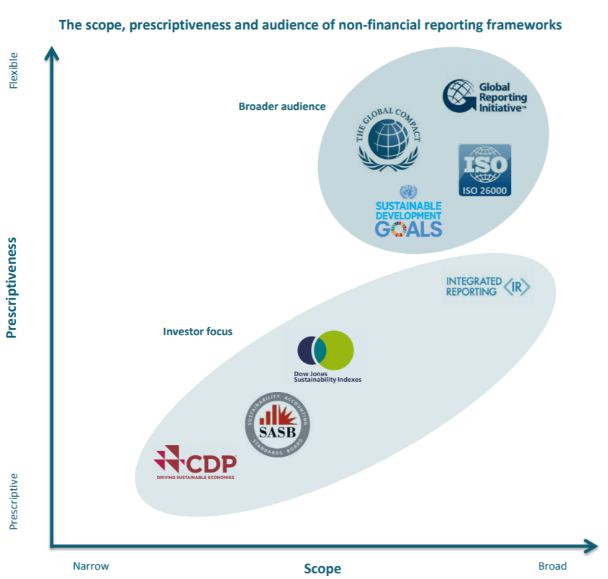

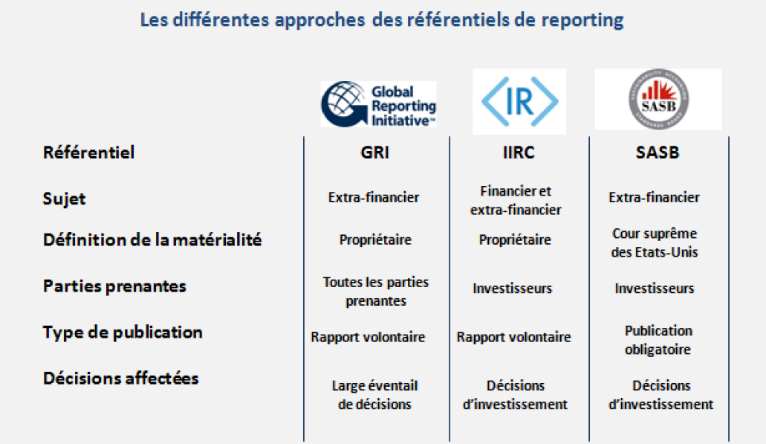

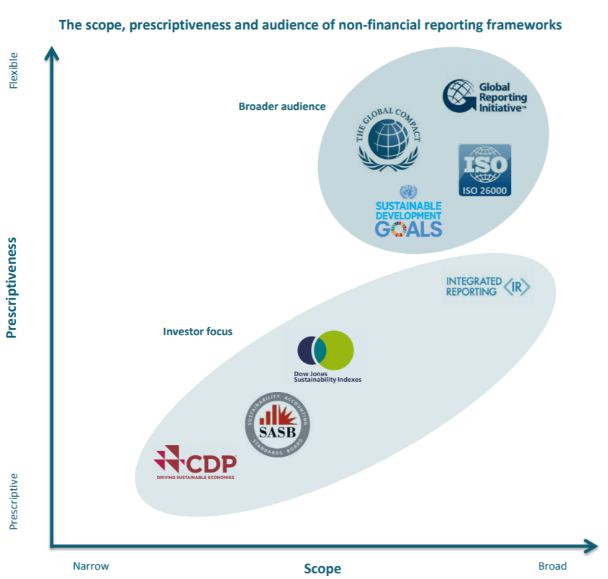

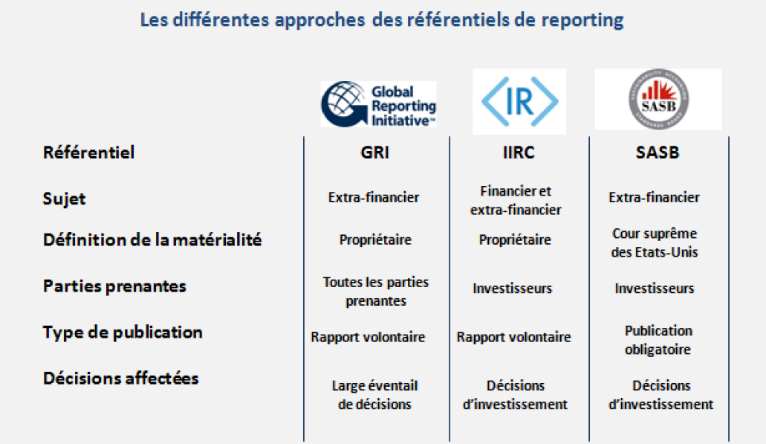

La définition de la matérialité diverge ainsi entre pays ce qui vient se répercuter dans l’information divulguée par les entreprises. Il ne faut pas non plus oublier la différence qu’il existe lorsqu’une entreprise se soumet à différents référentiels volontaires : Global Reporting Initiative (GRI), International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP), de l’Organisation internationale de normalisation (ISO 26000) …

Source : Greenstone – Choosing the right non-financial reporting frameworks / Tennaxia, Livre Blanc « Réaliser une analyse de matérialité » septembre 2018 2ième édition

Cette différence dans la définition de matérialité a une incidence sur la communication de l’entreprise. Ainsi, un rapport fondé sur une matérialité au sens du GRI aura comme objectif de toucher un large public, alors qu’au contraire, un rapport fondé sur les normes du SASB s’adressera plutôt aux investisseurs et la manière dont ils peuvent prendre leurs décisions[13].

Conclusion

La matérialité est donc essentielle pour le reporting extra-financier puisqu’il donne du sens au travail de fond qui se fait en amont de la divulgation. Cependant, cette diversité des définitions obère d’une certaine manière une plus grande transparence et la comparabilité entre entreprises dans l’information communiquée. Malgré tout, une attention particulière à cette analyse de matérialité ne peut être que bénéfique pour l’entreprise : une plus grande lisibilité des risques, de la création de valeur[14] sur le long terme et un meilleur dialogue entre parties prenantes ne peuvent que tirer l’entreprise vers le haut.

[1] Tennaxia, « Réaliser une analyse de matérialité », Septembre 2018, en ligne : http://www2.tennaxia.com/actualites/publications/analyse-de-materialite.

[2] Ibid, p 11.

[3] Thibault Lescuyer, « Reporting : la matrice de matérialité́, vous connaissez ? », Les Echos, en ligne : http://archives.lesechos.fr/archives/cercle/2014/04/18/cercle_95963.htm.

[4] Voir notamment l’Ordonnance n° 2017-1180 du 19 juillet 2017, JO, 21 juillet 2017, 169 et le Décret n° 2017-1265 du 9 août 2017, JO 11 août 2017, 25.

[5] Béatrice Parance et Élise Groulx, « La déclaration de performance extra-financière. – Nouvelle ambition du reporting-extra-financier » (2018) 11 JCP E 1128, par. 2.

[6] Ibid, par. 22.

[7] Une liste de sujets est à disposition des sociétés à l’art. R. 225-105 du C. com. Voir : Nicolas Cuzacq, « Le nouveau visage du reporting extra-financier français » (2018) 6 Revue des sociétés 357, par. 30 (cet auteur y voit une manière de « guider » et faire prendre conscience de certaines problématiques aux sociétés).

[8] MEDEF, « Guide : Reporting RSE. Déclaration de performance extra-financière », septembre 2017, p 3, en ligne : https://www.medef.com/uploads/media/node/0001/12/f6ee1c6ad233ebb1fa87922f046d062b59f1a4b2.pdf.

[9] Indications en matière d’information environnementale, ACVM Avis 51-333, (27 octobre 2010), p 5, en ligne : https://lautorite.qc.ca/fileadmin/lautorite/reglementation/valeurs-mobilieres/0-avis-acvm-staff/2010/2010oct27-51-333-acvm-fr.pdf.

[10] U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, « Form 10-K », en ligne : https://www.sec.gov/fast-answers/answers-form10khtm.html.

[11] Voir par exemple : Sustainability Accounting Standards Board, « Construction Materials Sustainability Accounting Standard », June 2014, en ligne : https://www.sasb.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/NR0401_ProvisionalStandard_ConstructionMaterials.pdf.

[12] TSC Indus. v. Northway, Inc., 426 US 438, 449 (1976)

[13] Tennaxia, « Réaliser une analyse de matérialité », Septembre 2018, p 12, en ligne : http://www2.tennaxia.com/actualites/publications/analyse-de-materialite.

[14] Ibid, p 22.