Nouvelles diverses | Page 11

actualités internationales Divulgation Gouvernance normes de droit

Réforme allemande à venir en gouvernance

Ivan Tchotourian 26 octobre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans Le Monde, Mme Cécile Boutelet propose une belle synthèse de réformes à venir du côté allemand suite au scandale Wirecard : « Après le scandale Wirecard, la finance allemande à la veille d’une profonde réforme » (Le Monde, 26 octobre 2020).

Extrait :

Après les révélations sur l’entreprise, qui avait manipulé son bilan, un projet de loi en discussion souhaite notamment renforcer les pouvoirs du gendarme de la Bourse allemand.

La finance allemande a-t-elle des pratiques malsaines ? Depuis la faillite au mois de juin de l’ancienne star de la finance Wirecard, après qu’elle a reconnu avoir lourdement manipulé son bilan, les révélations sur l’affaire se sont accumulées, soulignant les graves insuffisances du système de contrôle des marchés financiers outre-Rhin. Des manquements qui sont devenus un enjeu politique majeur. Sous pression, le ministre des finances, Olaf Scholz, pousse en faveur d’une réforme rapide du système. Son projet de loi, en discussion depuis mercredi 21 octobre dans les ministères, doit être voté « avant l’été », a-t-il annoncé.

Le texte, porté également par la ministre de la justice, Christine Lambrecht, révèle en creux les limites de l’approche allemande en matière de surveillance des entreprises cotées, et le tournant culturel amorcé par le scandale Wirecard. Le système reposait jusqu’ici sur la responsabilisation et la participation consensuelle des sociétés au processus de contrôle des bilans. L’examen des comptes était confié non pas à la BaFin, le gendarme allemand de la Bourse, mais à une association privée, la DPR (« organisme de contrôle des bilans »), qui disposait de très peu de moyens réels. L’affaire Wirecard a montré l’impuissance de cette approche dans le cas d’une fraude délibérément orchestrée. La future loi doit renforcer considérablement les pouvoirs de la BaFin, qui disposera d’un droit d’investigation pour examiner elle-même les bilans des entreprise

(…) Les cabinets d’audit, dont le manque de zèle à alerter sur les irrégularités de bilan a été mis au jour par le scandale, devront aussi se soumettre à une réforme. Leur mandat au service d’une même entreprise ne pourra excéder dix ans. Le projet de loi exige qu’une séparation plus nette soit faite, au sein de ces cabinets, entre leur activité d’audit et leur activité de conseil, afin d’éviter les conflits d’intérêts.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

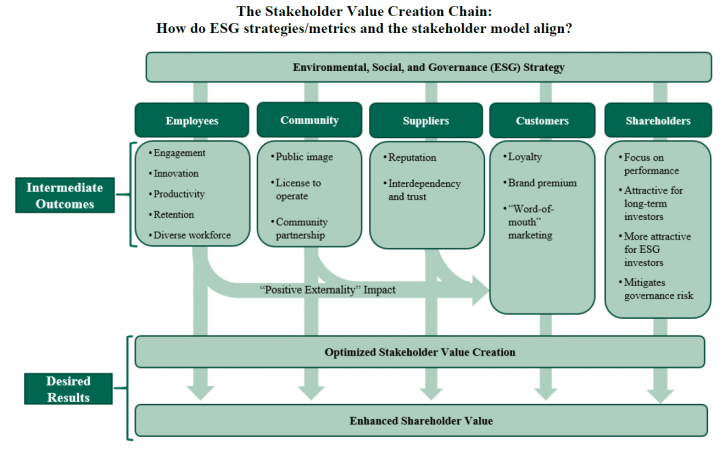

The Stakeholder Model and ESG

Ivan Tchotourian 17 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Intéressant article sur l’Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance consacré au modèle partie prenante et à ses liens avec les critères ESG : « The Stakeholder Model and ESG » (Ira Kay, Chris Brindisi et Blaine Martin, 14 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Is your company ready to set or disclose ESG incentive goals?

ESG incentive metrics are like any other incentive metric: they should support and reinforce strategy rather than lead it. Companies considering ESG incentive metrics should align planning with the company’s social responsibility and environmental strategies, reporting, and goals. Another essential factor in determining readiness is the measurability/quantification of the specific ESG issue.

Companies will generally fall along a spectrum of readiness to consider adopting and disclosing ESG incentive metrics and goals:

- Companies Ready to Set Quantitative ESG Goals: Companies with robust environmental, sustainability, and/or social responsibility strategies including quantifiable metrics and goals (e.g., carbon reduction goals, net zero carbon emissions commitments, Diversity and Inclusion metrics, employee and environmental safety metrics, customer satisfaction, etc.).

- Companies Ready to Set Qualitative Goals: Companies with evolving formalized tracking and reporting but for which ESG matters have been identified as important factors to customers, employees, or other These companies likely already have plans or goals around ESG factors (e.g., LEED [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design]-certified office space, Diversity and Inclusion initiatives, renewable power and emissions goals, etc.).

- Companies Developing an ESG Strategy: Some companies are at an early stage of developing overall ESG/stakeholder strategies. These companies may be best served to focus on developing a strategy for environmental and social impact before considering linking incentive pay to these priorities.

We note it is critically important that these ESG/stakeholder metrics and goals be chosen and set with rigor in the same manner as financial metrics to ensure that the attainment of the ESG goals will enhance stakeholder value and not serve simply as “window dressing” or “greenwashing.” [9] Implementing ESG metrics is a company-specific design process. For example, some companies may choose to implement qualitative ESG incentive goals even if they have rigorous ESG factor data and reporting.

Will ESG metrics and goals contribute to the company’s value-creation?

The business case for using ESG incentive metrics is to provide line-of-sight for the management team to drive the implementation of initiatives that create significant differentiated value for the company or align with current or emerging stakeholder expectations. Companies must first assess which metrics or initiatives will most benefit the company’s business and for which stakeholders. They must also develop challenging goals for these metrics to increase the likelihood of overall value creation. For example:

- Employees: Are employees and the competitive talent market driving the need for differentiated environmental or social initiatives? Will initiatives related to overall company sustainability (building sustainability, renewable energy use, net zero carbon emissions) contribute to the company being a “best in class” employer? Diversity and inclusion and pay equity initiatives have company and social benefits, such as ensuring fair and equitable opportunities to participate and thrive in the corporate system.

- Customers: Are customer preferences driving the need to differentiate on sustainable supply chains, social justice initiatives, and/or the product/company’s environmental footprint?

- Long-Term Sustainability: Are long-term macro environmental factors (carbon emissions, carbon intensity of product, etc.) critical to the Company’s ability to operate in the long term?

- Brand Image: Does a company want to be viewed by all constituencies, including those with no direct economic linkage, as a positive social and economic contributor to society?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to ESG metrics, and companies fall across a spectrum of needs and drivers that affect the type of ESG factors that are relevant to short- and long-term business value depending on scale, industry, and stakeholder drivers. Most companies have addressed, or will need to address, how to implement ESG/stakeholder considerations in their operating strategy.

Conceptual Design Parameters for Structuring Incentive Goals

For those companies moving to implement stakeholder/ESG incentive goals for the first time, the design parameters range widely, which is not different than the design process for implementing any incentive metric. For these companies, considering the following questions can help move the prospect of an ESG incentive metric from an idea to a tangible goal with the potential to create value for the company:

- Quantitative goals versus qualitative milestones. The availability and quality of data from sustainability or social responsibility reports will generally determine whether a company can set a defined quantitative goal. For other companies, lack of available ESG data/goals or the company’s specific pay philosophy may mean ESG initiatives are best measured by setting annual milestones tailored to selected goals.

- Selecting metrics aligned with value creation. Unlike financial metrics, for which robust statistical analyses can help guide the metric selection process (e.g., financial correlation analysis), the link between ESG metrics and company value creation is more nuanced and significantly impacted by industry, operating model, customer and employee perceptions and preferences, etc. Given this, companies should generally apply a principles-based approach to assess the most appropriate metrics for the company as a whole (e.g., assessing significance to the organization, measurability, achievability, etc.) Appendix 1 provides a list of common ESG metrics with illustrative mapping to typical stakeholder impact.

- Determining employee participation. Generally, stakeholder/ESG-focused metrics would be implemented for officer/executive level roles, as this is the employee group that sets company-wide policy impacting the achievement of quantitative ESG goals or qualitative milestones. Alternatively, some companies may choose to implement firm-wide ESG incentive metrics to reinforce the positive employee engagement benefits of the company’s ESG strategy or to drive a whole-team approach to achieving goals.

- Determining the range of metric weightings for stakeholder/ESG goals. Historically, US companies with existing environmental, employee safety, and customer service goals as well as other stakeholder metrics have been concentrated in the extractive, industrial, and utility industries; metric weightings on these goals have ranged from 5% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards. We expect that this weighting range would continue to apply, with the remaining 80%+ of annual incentive weighting focused on financial metrics. Further, we expect that proxy advisors and shareholders may react adversely to non-financial metrics weighted more than 10% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards.

- Considering whether to implement stakeholder/ESG goals in annual versus long-term incentive plans. As noted above, most ESG incentive goals to date have been implemented as weighted metrics in balanced scorecard annual incentive plans for several reasons. However, we have observed increased discussion of whether some goals (particularly greenhouse gas emission goals) may be better suited to long-term incentives. [10] There is no right answer to this question—some milestone and quantitative goals are best set on an annual basis given emerging industry, technology, and company developments; other companies may have a robust long-term plan for which longer-term incentives are a better fit.

- Considering how to operationalize ESG metrics into long-term plans. For companies determining that sustainability or social responsibility goals fit best into the framework of a long-term incentive, those companies will need to consider which vehicles are best to incentivize achievement of strategically important ESG goals. While companies may choose to dedicate a portion of a 3-year performance share unit plan to an ESG metric (e.g., weighting a plan 40% relative total shareholder return [TSR], 40% revenue growth, and 20% greenhouse gas reduction), there may be concerns for shareholders and/or participants in diluting the financial and shareholder-value focus of these incentives. As an alternative, companies could grant performance restricted stock units, vesting at the end of a period of time (e.g., 3 or 4 years) contingent upon achievement of a long-term, rigorous ESG performance milestone. This approach would not “dilute” the percentage of relative TSR and financial-based long-term incentives, which will remain important to shareholders and proxy advisors.

Conclusion

As priorities of stakeholders continue to evolve, and addressing these becomes a strategic imperative, companies may look to include some stakeholder metrics in their compensation programs to emphasize these priorities. As companies and Compensation Committees discuss stakeholder and ESG-focused incentive metrics, each organization must consider its unique industry environment, business model, and cultural context. We interpret the BRT’s updated statement of business purpose as a more nuanced perspective on how to create value for all stakeholders, inclusive of shareholders. While optimizing profits will remain the business purpose of corporations, the BRT’s statement provides support for prioritizing the needs of all stakeholders in driving long-term, sustainable success for the business. For some companies, implementing incentive metrics aligned with this broader context can be an important tool to drive these efforts in both the short and long term. That said, appropriate timing, design, and communication will be critical to ensure effective implementation.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Pour un comité social et éthique en matière de gouvernance

Ivan Tchotourian 17 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans BoardAgenda, Gavin Hinks propose une solution pour que les parties prenantes soient mieux pris en compte : la création d’un comité social et éthique (déjà en fonction en Afrique du Sud) : « Companies ‘need new mechanism’ to integrate stakeholder interests » (4 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

While section 172 of the Companies Act—the key law governing directors’ duties—has been sufficiently flexible to enable companies to re-align themselves with stakeholders so far, it provides no guarantee they will maintain that disposition.

In their recent paper, MacNeil and Esser argue more regulation is needed and in particular a mandatory committee drawing key stakeholder issues to the board and then reporting on them to shareholders.

Known as the “social and ethics committee” in South Africa, a similar mandatory committee in the UK considering ESG (environmental, social and governance) issues “will provide a level playing field for stakeholder engagement,” write MacNeil and Esser.

Recent evidence, they concede, suggests the committees in South Africa are still evolving, but there are advantages, with the committee “uniquely placed with direct access to the main board and a mandate to reach into the depths of the business”.

“As a result, it is capable of having a strong influence on the way a company heads down the path of sustained value creation.”

Will stakeholderism stick?

The issue of making “stakeholder” capitalism stick has vexed others too. The issue was a dominant agenda item at the World Economic Forum’s Davos conference this year, as well as becoming a key element in the presidential campaign of Democrat candidate Joe Biden.

Others worry that stakeholderism is a talking point only, prompting no real change in some companies. Indeed, when academics examined the practical policy outcomes from the now famous 2019 pledge by the Business Roundtable—a group of US multinationals—to shift their focus from shareholders to stakeholders, they found the companies wanting.

In the UK, at least, some are taking the issue very seriously. The Institute of Directors recently launched a new governance centre with its first agenda item being how stakeholderism can be integrated into current governance structures.

Further back the Royal Academy, an august British research institution, issued its own principles for becoming a “purposeful business”, another idea closely associated with stakeholderism.

The stakeholder debate has a long way to run. If the idea is to gain traction it will undoubtedly need a stronger commitment in regulation than it currently has, or companies could easily wander from the path. That may depend on public demand and political will. But Esser and MacNeil may have at least indicated one way forward.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement normes de droit objectifs de l'entreprise Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

50 years later, Milton Friedman’s shareholder doctrine is dead

Ivan Tchotourian 16 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Belle tribune dans Fortune de MM. Colin Mayer, Leo Strine Jr et Jaap Winter au titre clair : « 50 years later, Milton Friedman’s shareholder doctrine is dead » (13 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Fifty years ago, Milton Friedman in the New York Times magazine proclaimed that the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. Directors have the duty to do what is in the interests of their masters, the shareholders, to make as much profit as possible. Friedman was hostile to the New Deal and European models of social democracy and urged business to use its muscle to reduce the effectiveness of unions, blunt environmental and consumer protection measures, and defang antitrust law. He sought to reduce consideration of human concerns within the corporate boardroom and legal requirements on business to treat workers, consumers, and society fairly.

Over the last 50 years, Friedman’s views became increasingly influential in the U.S. As a result, the power of the stock market and wealthy elites soared and consideration of the interests of workers, the environment, and consumers declined. Profound economic insecurity and inequality, a slow response to climate change, and undermined public institutions resulted. Using their wealth and power in the pursuit of profits, corporations led the way in loosening the external constraints that protected workers and other stakeholders against overreaching.

Under the dominant Friedman paradigm, corporations were constantly harried by all the mechanisms that shareholders had available—shareholder resolutions, takeovers, and hedge fund activism—to keep them narrowly focused on stockholder returns. And pushed by institutional investors, executive remuneration systems were increasingly focused on total stock returns. By making corporations the playthings of the stock market, it became steadily harder for corporations to operate in an enlightened way that reflected the real interests of their human investors in sustainable growth, fair treatment of workers, and protection of the environment.

Half a century later, it is clear that this narrow, stockholder-centered view of corporations has cost society severely. Well before the COVID-19 pandemic, the single-minded focus of business on profits was criticized for causing the degradation of nature and biodiversity, contributing to global warming, stagnating wages, and exacerbating economic inequality. The result is best exemplified by the drastic shift in gain sharing away from workers toward corporate elites, with stockholders and top management eating more of the economic pie.

Corporate America understood the threat that this way of thinking was having on the social compact and reacted through the 2019 corporate purpose statement of the Business Roundtable, emphasizing responsibility to stakeholders as well as shareholders. But the failure of many of the signatories to protect their stakeholders during the coronavirus pandemic has prompted cynicism about the original intentions of those signing the document, as well as their subsequent actions.

Stockholder advocates are right when then they claim that purpose statements on their own achieve little: Calling for corporate executives who answer to only one powerful constituency—stockholders in the form of highly assertive institutional investors—and have no legal duty to other stakeholders to run their corporations in a way that is fair to all stakeholders is not only ineffectual, it is naive and intellectually incoherent.

What is required is to match commitment to broader responsibility of corporations to society with a power structure that backs it up. That is what has been missing. Corporate law in the U.S. leaves it to directors and managers subject to potent stockholder power to give weight to other stakeholders. In principle, corporations can commit to purposes beyond profit and their stakeholders, but only if their powerful investors allow them to do so. Ultimately, because the law is permissive, it is in fact highly restrictive of corporations acting fairly for all their stakeholders because it hands authority to investors and financial markets for corporate control.

Absent any effective mechanism for encouraging adherence to the Roundtable statement, the system is stacked against those who attempt to do so. There is no requirement on corporations to look after their stakeholders and for the most part they do not, because if they did, they would incur the wrath of their shareholders. That was illustrated all too clearly by the immediate knee-jerk response of the Council of Institutional Investors to the Roundtable declaration last year, which expressed its disapproval by stating that the Roundtable had failed to recognize shareholders as owners as well as providers of capital, and that “accountability to everyone means accountability to no one.”

If the Roundtable is serious about shifting from shareholder primacy to purposeful business, two things need to happen. One is that the promise of the New Deal needs to be renewed, and protections for workers, the environment, and consumers in the U.S. need to be brought closer to the standards set in places like Germany and Scandinavia.

But to do that first thing, a second thing is necessary. Changes within company law itself must occur, so that corporations are better positioned to support the restoration of that framework and govern themselves internally in a manner that respects their workers and society. Changing the power structure within corporate law itself—to require companies to give fair consideration to stakeholders and temper their need to put profit above all other values—will also limit the ability and incentives for companies to weaken regulations that protect workers, consumers, and society more generally.

To make this change, corporate purpose has to be enshrined in the heart of corporate law as an expression of the broader responsibility of corporations to society and the duty of directors to ensure this. Laws already on the books of many states in the U.S. do exactly that by authorizing the public benefit corporation (PBC). A PBC has an obligation to state a public purpose beyond profit, to fulfill that purpose as part of the responsibilities of its directors, and to be accountable for so doing. This model is meaningfully distinct from the constituency statutes in some states that seek to strengthen stakeholder interests, but that stakeholder advocates condemn as ineffectual. PBCs have an affirmative duty to be good corporate citizens and to treat all stakeholders with respect. Such requirements are mandatory and meaningful, while constituency statutes are mushy.

The PBC model is growing in importance and is embraced by many younger entrepreneurs committed to the idea that making money in a way that is fair to everyone is the responsible path forward. But the model’s ultimate success depends on longstanding corporations moving to adopt it.

Even in the wake of the Roundtable’s high-minded statement, that has not yet happened, and for good reason. Although corporations can opt in to become a PBC, there is no obligation on them to do so and they need the support of their shareholders. It is relatively easy for founder-owned companies or companies with a relatively low number of stockholders to adopt PBC forms if their owners are so inclined. It is much tougher to obtain the approval of a dispersed group of institutional investors who are accountable to an even more dispersed group of individual investors. There is a serious coordination problem of achieving reform in existing corporations.

That is why the law needs to change. Instead of being an opt-in alternative to shareholder primacy, the PBC should be the universal standard for societally important corporations, which should be defined as ones with over $1 billion of revenues, as suggested by Sen. Elizabeth Warren. In the U.S., this would be done most effectively by corporations becoming PBCs under state law. The magic of the U.S. system has rested in large part on cooperation between the federal government and states, which provides society with the best blend of national standards and nimble implementation. This approach would build on that.

Corporate shareholders and directors enjoy substantial advantages and protections through U.S. law that are not extended to those who run their own businesses. In return for offering these privileges, society can reasonably expect to benefit, not suffer, from what corporations do. Making responsibility in society a duty in corporate law will reestablish the legitimacy of incorporation.

There are three pillars to this. The first is that corporations must be responsible corporate citizens, treating their workers and other stakeholders fairly, and avoiding externalities, such as carbon emissions, that cause unreasonable or disproportionate harm to others. The second is that corporations should seek to make profit by benefiting others. The third is that they should be able to demonstrate that they fulfill both criteria by measuring and reporting their performances against them.

The PBC model embraces all three elements and puts legal, and thus market, force behind them. Corporate managers, like most of us, take obligatory duties seriously. If they don’t, the PBC model allows for courts to issue orders, such as injunctions, holding corporations to their stakeholder and societal obligations. In addition, the PBC model requires fairness to all stakeholders at all stages of a corporation’s life, even when it is sold. The PBC model shifts power to socially responsible investment and index funds that focus on the long term and cannot gain from unsustainable approaches to growth that harm society.

Our proposal to amend corporate law to ensure responsible corporate citizenship will prompt a predictable outcry from vested interests and traditional academic quarters, claiming that it will be unworkable, devastating for entrepreneurship and innovation, undermine a capitalist system that has been an engine for growth and prosperity, and threaten jobs, pensions, and investment around the world. If putting the purpose of a business at the heart of corporate law does all of that, one might well wonder why we invented the corporation in the first place.

Of course, it will do exactly the opposite. Putting purpose into law will simplify, not complicate, the running of businesses by aligning what the law wants them to do with the reason why they are created. It will be a source of entrepreneurship, innovation, and inspiration to find solutions to problems that individuals, societies, and the natural world face. It will make markets and the capitalist system function better by rewarding positive contributions to well-being and prosperity, not wealth transfers at the expense of others. It will create meaningful, fulfilling jobs, support employees in employment and retirement, and encourage investment in activities that generate wealth for all.

We are calling for the universal adoption of the PBC for large corporations. We do so to save our capitalist system and corporations from the devastating consequences of their current approaches, and for the sake of our children, our societies, and the natural world.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement place des salariés rémunération

Entreprises européennes, salariés et dividendes : tendance

Ivan Tchotourian 16 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans un article du Financial Times (« European companies were more keen to cut divis than executive pay », 9 septembre 2020), il est observé que les assemblées annuelles de grandes entreprises européennes montrent des disparités concernant la protection des salariés et la réduction des dividendes.

Extrait :

Businesses in Spain, Italy, the Netherlands and the UK were more likely to cut dividends than executive pay this year, despite calls from shareholders for bosses to share the financial pain caused by the pandemic.

More than half of Spanish businesses examined by Georgeson, a corporate governance consultancy, cancelled, postponed or reduced dividends in 2020. Only 29 per cent introduced a temporary reduction in executive pay. In Italy, 44 per cent of companies changed their dividend policies because of Covid-19, but just 29 per cent cut pay for bosses, according to the review of the annual meeting season in Europe.

This disparity between protection of salaries and bonuses at the top while shareholders have been hit with widespread dividend cuts is emerging as a flashpoint for investors. Asset managers such as Schroders and M&G have spoken out about the need for companies to show restraint on pay if they are cutting dividends or receiving government support. “Executive remuneration remains a key focal point for investors and was amongst the most contested resolutions in the majority of the markets,” said Georgeson’s Domenic Brancati.

But he added that despite this focus, shareholder revolts over executive pay had fallen slightly across Europe compared with 2019 — suggesting that investors were giving companies some leeway on how they dealt with the pandemic. Investors could become more vocal about this issue next year, he said.

One UK-based asset manager said it was “still having lots of conversations with companies around pay” but for this year had decided not to vote against companies on the issue. But it added the business would watch remuneration and dividends closely next year.

Companies around the world have cut or cancelled dividends in response to the crisis, hitting income streams for many investors. According to Janus Henderson, global dividends had their biggest quarterly fall in a decade during the second quarter, with more than $100bn wiped off their value. The Georgeson data shows that almost half of UK companies changed their dividend payout, while less than 45 per cent altered executive remuneration. In the Netherlands, executive pay took a hit at 29 per cent of companies, while 34 per cent adjusted dividends. In contrast, a quarter of Swiss executives were hit with a pay cut but only a fifth of companies cut or cancelled their dividend.

The Georgeson research also found that the pandemic had a significant impact on the AGM process across Europe, with many companies postponing their annual meetings or stopping shareholders from voting during the event.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales devoirs des administrateurs Gouvernance normes de droit Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Sustainable Value Creation Within Planetary Boundaries—Reforming Corporate Purpose and Duties of the Corporate Board

Ivan Tchotourian 14 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Ma collègue Beate Sjåfjell nous gâte encore avec un très bel article (accessible en ligne !) : « Sustainable Value Creation Within Planetary Boundaries—Reforming Corporate Purpose and Duties of the Corporate Board » (Sustainibility, 2020, Vol. 12, Issue 15). Je vous conseille vivement la lecture de cet article…

Résumé :

Business, and the dominant legal form of business, that is, the corporation, must be involved in the transition to sustainability, if we are to succeed in securing a safe and just space for humanity. The corporate board has a crucial role in determining the strategy and the direction of the corporation. However, currently, the function of the corporate board is constrained through the social norm of shareholder primacy, reinforced through the intermediary structures of capital markets. This article argues that an EU law reform is key to integrating sustainability into mainstream corporate governance, into the corporate purpose and the core duties of the corporate board, to change corporations from within. While previous attempts at harmonizing core corporate law at the EU level have failed, there are now several drivers for reform that may facilitate a change, including the EU Commission’s increased emphasis on sustainability. Drawing on this momentum, this article presents a proposal to reform corporate purpose and duties of the board, based on the results of the EU-funded research project, Sustainable Market Actors for Responsible Trade (SMART, 2016–2020).

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance rémunération

High Pay Center : rapport et impact de la COVID-19

Ivan Tchotourian 12 août 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Le High Pay Centre anglais vient de publier son rapport 2019 sur la rémunération des hauts dirigeants : « HPC/CIPD Annual FTSE 100 CEO Pay Review – CEO pay flat in 2019 ». Je vous laisse découvrir les chiffres, mais j’attire votre attention sur les conséquences de la COVID-19.

Extrait :

Covid-19 pay cuts

- 36 FTSE 100 companies have announced cuts to executive pay in response to the COVID-19 crisis and economic downturn.

- While most of the 36 companies have used a combination of measures to cut pay, the report suggests these are mainly superficial or short-term. The most common measure, taken by 14 companies, has been to cut salaries at the top by 20%. However, salaries typically only make up a small part of a FTSE 100 CEO’s total pay package.

- 11 companies have cancelled Short-Term Incentive Plans (STIPs) for their CEOs while two other firms have deferred salary increases for their CEOs. None of the 36 companies have chosen to reduce their CEO’s Long-Term Incentive Plan (LTIP), which typically makes up half of a CEO’s total pay package.

À la prochaine…