Gouvernance | Page 16

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration place des salariés Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Salariés dans les CA = moins bonne performance ?

Ivan Tchotourian 24 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans The conversation, les chercheurs Nagati, Boukadhaba et Nekhili livrent un constat étonnant sur la présence des salariés dans les CA en France : oui, ils sont plus présents que par le passé, mais leur impact sur la performance de l’entreprise est critiquable… d’où la méfiance des actionnaires ! (« Salariés dans les conseils d’administration : une présence qui dérange les actionnaires… », 17 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Une gouvernance de plus en plus partenariale

Pour ce qui est des critères de gouvernance, la régulation du mode de fonctionnement du conseil d’administration n’a ainsi cessé d’évoluer ces dernières années. Celle-ci contraint davantage les entreprises à une plus grande diversité des membres du conseil d’administration, qui intègrent notamment de plus en plus de salariés.

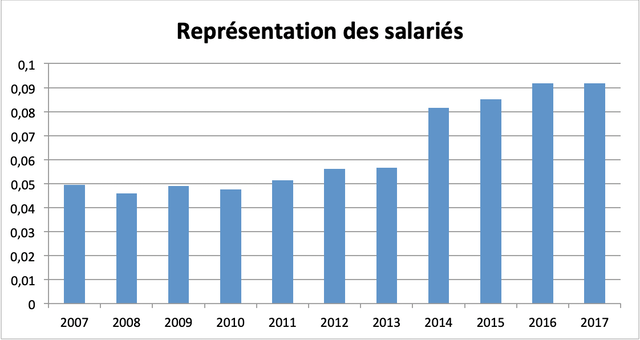

Le taux moyen de représentation des salariés dans le conseil d’administration des sociétés non financières du SBF 120 a ainsi évolué de 4,95 % en 2007 à 9,17 % en 2017 (voir graphique ci-dessous).

Une augmentation significative est notamment constatée à partir de 2014. Celle-ci s’explique par la loi n° 2013-504 de 14 juin 2013 relative à la sécurisation de l’emploi rendant obligatoire la présence d’au moins deux représentants de salariés pour les entreprises ayant des conseils d’administration de plus de 12 administrateurs et d’au moins un représentant pour les autres.

Cela témoigne de la volonté de s’orienter vers une gouvernance partenariale (stakeholders) qui s’oppose, dans ses grands principes, à la gouvernance actionnariale (shareholders).

Or, la présence de salariés au sein des conseils d’administration est généralement vue d’un mauvais œil par les actionnaires. C’est ce qui ressort de notre article de recherche publié en 2019 dans la revue International Journal of Human Resource Management sous le titre ESG Performance and Market Value : the Moderating Role of Employee Board Representation.

Cette étude porte sur un échantillon de grandes entreprises françaises non financières de l’indice SBF 120 durant la période 2007-2017.

À travers l’appréciation de la performance boursière des entreprises, les résultats de nos estimations montrent que, si le marché financier réagit positivement à la performance extrafinancière, il reste néanmoins réticent à la représentation des salariés dans le conseil d’administration.

En effet, la valeur moyenne de la performance boursière, mesurée par le Q de Tobin (rapport entre la somme de la capitalisation boursière et de la valeur de la dette, d’une part, et le total de l’actif du bilan, d’autre part), est de 1,142 chez les entreprises d’au moins un administrateur représentant des salariés contre 1,271 chez les entreprises n’ayant pas d’administrateurs représentants de salariés.

Conflits d’intérêts

De toute évidence, les actionnaires sont sensibles à la réalisation d’une bonne performance extrafinancière dont ils supportent à eux seuls les coûts s’y rapportant. Cependant, les actionnaires peuvent aussi voir dans la réalisation d’une bonne performance extrafinancière une stratégie pour les dirigeants de s’enraciner en jouant la carte des autres stakeholders, principalement les salariés, dont les intérêts ne coïncident pas nécessairement avec leurs propres intérêts.

Pour les actionnaires, donner des droits de vote aux salariés au sein du conseil d’administration peut donc contrebalancer leur pouvoir, mettant fin à leur suprématie, si relative soit-elle, dans le processus décisionnel.

Partant de l’idée qu’il existe une relation, souvent entretenue par des intérêts communs, entre les dirigeants et les employés, les recherches antérieures mettent en avant le postulat que les dirigeants peuvent procéder à l’augmentation des investissements sociétaux dans un objectif moins louable qui est celui de gagner le soutien et la confiance des salariés pour se soustraire du pouvoir, parfois excessif, des actionnaires.

De surcroît, la réalisation d’un niveau élevé de performance extrafinancière doublée par la nomination des administrateurs salariés dans le conseil d’administration ne peut que renforcer le sentiment de prudence des actionnaires envers les choix stratégiques des dirigeants en matière de développement sociétal.

Les mêmes résultats sont aussi trouvés lorsqu’on considère individuellement les différents piliers de la performance extrafinancière (environnemental, social, et de gouvernance). Nos conclusions confortent l’idée de la présence de conflits d’intérêts majeurs entre les actionnaires et les salariés autour des questions relatives au développement sociétal.

En somme, nos résultats interrogent la façon dont la participation des salariés à la prise de décision est conçue et présentée aux investisseurs financiers. Ces enseignements devraient inciter les entreprises à renforcer leurs efforts de formation et de communication pour plaider en faveur de l’adoption d’un conseil d’administration ouvert aux différentes parties prenantes.

Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Structures juridiques

Purpose et revitalisation du droit des sociétés

Ivan Tchotourian 24 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

La professeure australienne Rosemary Teele Langford offre un bel article relayé par l’Oxford Business Law Blog : « Purpose-Based Governance and Revitalisation of Company Law to Facilitate Purpose-Based Companies » (18 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

The permissibility of corporations pursuing purposes other than profit has been the subject of debate for a number of years. This debate has intensified recently with proposals from bodies such as the British Academy and the Business Round Table (as discussed in previous OBLB posts) to allow or mandate the adoption of purposes by corporations. The challenges posed by COVID-19 have also focused attention on corporate purpose. In addition, there is increasing demand for appropriate vehicles for the conduct of social enterprises and other purpose-based ventures. At the same time, purpose is central to governance in the charitable sphere. In two recent articles I critically analyse the role of purpose in Australian company and charity law and demonstrate revitalisation of the law to facilitate adoption of, and governance centred on, purpose.

(…)

The second article, ‘Use of the Corporate Form for Public Benefit – Revitalisation of Australian Corporations Law’, provides extended detail on relevant aspects of the company law regime and focuses more closely on particular issues that arise in the facilitation of purpose-based companies. These include the application of directors’ duties in the context of such companies, with particular focus on the application of the duty to act in good faith in the interests of the company where companies have multiple purposes. This in turn has relevance for the drafting of appropriate constitutional provisions. Other issues arise in relation to standing and enforcement, departure from purposes and signalling. The focus of analysis is on the for-profit corporate form given that it is uncontroversial that other corporate forms (such as companies limited by guarantee) can be used for charitable and not-for-profit purposes.

In this respect, experience from the UK and US can provide helpful insights in the revitalisation of Australian law. In particular, scholarly analysis of the issues arising from these overseas legislative regimes, and suggested solutions, are invaluable in determining the application of directors’ duties to purpose-based companies and in framing appropriate constitutional provisions. Although changes to the law are not necessary to enable companies to adopt purposes, these lessons from other jurisdictions that have legislated to allow for special-purpose companies are therefore instructive in revitalising Australian law.

This analysis demonstrates that revitalisation of Australian law to allow purpose-based companies is feasible. In fact, it is opportune. This in turn allows company law to be attuned to practical and conceptual developments in the corporate sphere and more broadly. Such revitalisation does not require a fundamental shift, particularly given the malleability of directors’ duties. Indeed, given that the origins of the corporate form were connected with public ends, this evolution of the corporate form, and the attendant adaption of directors’ duties, are a natural adaptation rather than a radical reformulation.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Nouvelles diverses parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

The Stakeholder Model and ESG

Ivan Tchotourian 17 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Intéressant article sur l’Harvard Law School Forum on Corporate Governance consacré au modèle partie prenante et à ses liens avec les critères ESG : « The Stakeholder Model and ESG » (Ira Kay, Chris Brindisi et Blaine Martin, 14 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Is your company ready to set or disclose ESG incentive goals?

ESG incentive metrics are like any other incentive metric: they should support and reinforce strategy rather than lead it. Companies considering ESG incentive metrics should align planning with the company’s social responsibility and environmental strategies, reporting, and goals. Another essential factor in determining readiness is the measurability/quantification of the specific ESG issue.

Companies will generally fall along a spectrum of readiness to consider adopting and disclosing ESG incentive metrics and goals:

- Companies Ready to Set Quantitative ESG Goals: Companies with robust environmental, sustainability, and/or social responsibility strategies including quantifiable metrics and goals (e.g., carbon reduction goals, net zero carbon emissions commitments, Diversity and Inclusion metrics, employee and environmental safety metrics, customer satisfaction, etc.).

- Companies Ready to Set Qualitative Goals: Companies with evolving formalized tracking and reporting but for which ESG matters have been identified as important factors to customers, employees, or other These companies likely already have plans or goals around ESG factors (e.g., LEED [Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design]-certified office space, Diversity and Inclusion initiatives, renewable power and emissions goals, etc.).

- Companies Developing an ESG Strategy: Some companies are at an early stage of developing overall ESG/stakeholder strategies. These companies may be best served to focus on developing a strategy for environmental and social impact before considering linking incentive pay to these priorities.

We note it is critically important that these ESG/stakeholder metrics and goals be chosen and set with rigor in the same manner as financial metrics to ensure that the attainment of the ESG goals will enhance stakeholder value and not serve simply as “window dressing” or “greenwashing.” [9] Implementing ESG metrics is a company-specific design process. For example, some companies may choose to implement qualitative ESG incentive goals even if they have rigorous ESG factor data and reporting.

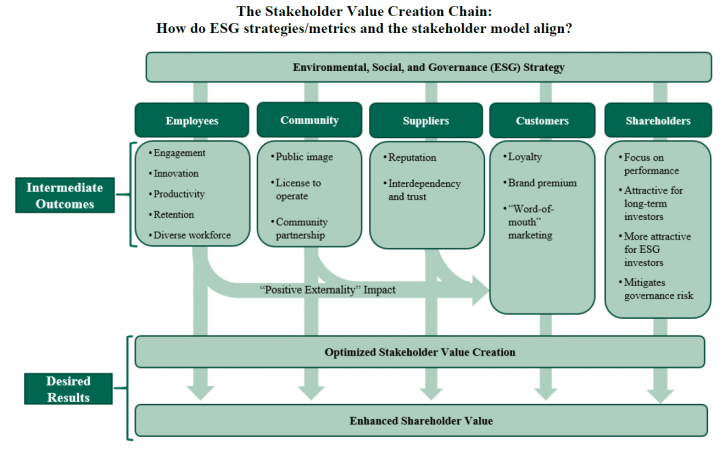

Will ESG metrics and goals contribute to the company’s value-creation?

The business case for using ESG incentive metrics is to provide line-of-sight for the management team to drive the implementation of initiatives that create significant differentiated value for the company or align with current or emerging stakeholder expectations. Companies must first assess which metrics or initiatives will most benefit the company’s business and for which stakeholders. They must also develop challenging goals for these metrics to increase the likelihood of overall value creation. For example:

- Employees: Are employees and the competitive talent market driving the need for differentiated environmental or social initiatives? Will initiatives related to overall company sustainability (building sustainability, renewable energy use, net zero carbon emissions) contribute to the company being a “best in class” employer? Diversity and inclusion and pay equity initiatives have company and social benefits, such as ensuring fair and equitable opportunities to participate and thrive in the corporate system.

- Customers: Are customer preferences driving the need to differentiate on sustainable supply chains, social justice initiatives, and/or the product/company’s environmental footprint?

- Long-Term Sustainability: Are long-term macro environmental factors (carbon emissions, carbon intensity of product, etc.) critical to the Company’s ability to operate in the long term?

- Brand Image: Does a company want to be viewed by all constituencies, including those with no direct economic linkage, as a positive social and economic contributor to society?

There is no one-size-fits-all approach to ESG metrics, and companies fall across a spectrum of needs and drivers that affect the type of ESG factors that are relevant to short- and long-term business value depending on scale, industry, and stakeholder drivers. Most companies have addressed, or will need to address, how to implement ESG/stakeholder considerations in their operating strategy.

Conceptual Design Parameters for Structuring Incentive Goals

For those companies moving to implement stakeholder/ESG incentive goals for the first time, the design parameters range widely, which is not different than the design process for implementing any incentive metric. For these companies, considering the following questions can help move the prospect of an ESG incentive metric from an idea to a tangible goal with the potential to create value for the company:

- Quantitative goals versus qualitative milestones. The availability and quality of data from sustainability or social responsibility reports will generally determine whether a company can set a defined quantitative goal. For other companies, lack of available ESG data/goals or the company’s specific pay philosophy may mean ESG initiatives are best measured by setting annual milestones tailored to selected goals.

- Selecting metrics aligned with value creation. Unlike financial metrics, for which robust statistical analyses can help guide the metric selection process (e.g., financial correlation analysis), the link between ESG metrics and company value creation is more nuanced and significantly impacted by industry, operating model, customer and employee perceptions and preferences, etc. Given this, companies should generally apply a principles-based approach to assess the most appropriate metrics for the company as a whole (e.g., assessing significance to the organization, measurability, achievability, etc.) Appendix 1 provides a list of common ESG metrics with illustrative mapping to typical stakeholder impact.

- Determining employee participation. Generally, stakeholder/ESG-focused metrics would be implemented for officer/executive level roles, as this is the employee group that sets company-wide policy impacting the achievement of quantitative ESG goals or qualitative milestones. Alternatively, some companies may choose to implement firm-wide ESG incentive metrics to reinforce the positive employee engagement benefits of the company’s ESG strategy or to drive a whole-team approach to achieving goals.

- Determining the range of metric weightings for stakeholder/ESG goals. Historically, US companies with existing environmental, employee safety, and customer service goals as well as other stakeholder metrics have been concentrated in the extractive, industrial, and utility industries; metric weightings on these goals have ranged from 5% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards. We expect that this weighting range would continue to apply, with the remaining 80%+ of annual incentive weighting focused on financial metrics. Further, we expect that proxy advisors and shareholders may react adversely to non-financial metrics weighted more than 10% to 20% of annual incentive scorecards.

- Considering whether to implement stakeholder/ESG goals in annual versus long-term incentive plans. As noted above, most ESG incentive goals to date have been implemented as weighted metrics in balanced scorecard annual incentive plans for several reasons. However, we have observed increased discussion of whether some goals (particularly greenhouse gas emission goals) may be better suited to long-term incentives. [10] There is no right answer to this question—some milestone and quantitative goals are best set on an annual basis given emerging industry, technology, and company developments; other companies may have a robust long-term plan for which longer-term incentives are a better fit.

- Considering how to operationalize ESG metrics into long-term plans. For companies determining that sustainability or social responsibility goals fit best into the framework of a long-term incentive, those companies will need to consider which vehicles are best to incentivize achievement of strategically important ESG goals. While companies may choose to dedicate a portion of a 3-year performance share unit plan to an ESG metric (e.g., weighting a plan 40% relative total shareholder return [TSR], 40% revenue growth, and 20% greenhouse gas reduction), there may be concerns for shareholders and/or participants in diluting the financial and shareholder-value focus of these incentives. As an alternative, companies could grant performance restricted stock units, vesting at the end of a period of time (e.g., 3 or 4 years) contingent upon achievement of a long-term, rigorous ESG performance milestone. This approach would not “dilute” the percentage of relative TSR and financial-based long-term incentives, which will remain important to shareholders and proxy advisors.

Conclusion

As priorities of stakeholders continue to evolve, and addressing these becomes a strategic imperative, companies may look to include some stakeholder metrics in their compensation programs to emphasize these priorities. As companies and Compensation Committees discuss stakeholder and ESG-focused incentive metrics, each organization must consider its unique industry environment, business model, and cultural context. We interpret the BRT’s updated statement of business purpose as a more nuanced perspective on how to create value for all stakeholders, inclusive of shareholders. While optimizing profits will remain the business purpose of corporations, the BRT’s statement provides support for prioritizing the needs of all stakeholders in driving long-term, sustainable success for the business. For some companies, implementing incentive metrics aligned with this broader context can be an important tool to drive these efforts in both the short and long term. That said, appropriate timing, design, and communication will be critical to ensure effective implementation.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement parties prenantes Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Pour un comité social et éthique en matière de gouvernance

Ivan Tchotourian 17 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Dans BoardAgenda, Gavin Hinks propose une solution pour que les parties prenantes soient mieux pris en compte : la création d’un comité social et éthique (déjà en fonction en Afrique du Sud) : « Companies ‘need new mechanism’ to integrate stakeholder interests » (4 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

While section 172 of the Companies Act—the key law governing directors’ duties—has been sufficiently flexible to enable companies to re-align themselves with stakeholders so far, it provides no guarantee they will maintain that disposition.

In their recent paper, MacNeil and Esser argue more regulation is needed and in particular a mandatory committee drawing key stakeholder issues to the board and then reporting on them to shareholders.

Known as the “social and ethics committee” in South Africa, a similar mandatory committee in the UK considering ESG (environmental, social and governance) issues “will provide a level playing field for stakeholder engagement,” write MacNeil and Esser.

Recent evidence, they concede, suggests the committees in South Africa are still evolving, but there are advantages, with the committee “uniquely placed with direct access to the main board and a mandate to reach into the depths of the business”.

“As a result, it is capable of having a strong influence on the way a company heads down the path of sustained value creation.”

Will stakeholderism stick?

The issue of making “stakeholder” capitalism stick has vexed others too. The issue was a dominant agenda item at the World Economic Forum’s Davos conference this year, as well as becoming a key element in the presidential campaign of Democrat candidate Joe Biden.

Others worry that stakeholderism is a talking point only, prompting no real change in some companies. Indeed, when academics examined the practical policy outcomes from the now famous 2019 pledge by the Business Roundtable—a group of US multinationals—to shift their focus from shareholders to stakeholders, they found the companies wanting.

In the UK, at least, some are taking the issue very seriously. The Institute of Directors recently launched a new governance centre with its first agenda item being how stakeholderism can be integrated into current governance structures.

Further back the Royal Academy, an august British research institution, issued its own principles for becoming a “purposeful business”, another idea closely associated with stakeholderism.

The stakeholder debate has a long way to run. If the idea is to gain traction it will undoubtedly need a stronger commitment in regulation than it currently has, or companies could easily wander from the path. That may depend on public demand and political will. But Esser and MacNeil may have at least indicated one way forward.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance normes de droit Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Raison d’être ou entreprise à mission, le faux débat

Ivan Tchotourian 16 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

C’est sous ce titre (« Raison d’être ou entreprise à mission, le faux débat », La Tribune, 2 septembre 2020) que M. Patrick d’Humières propose une lecture de la raison d’être et du statut d’entreprise à mission qui, selon lui, vont se rejoindre dans une trajectoire commune.

Extrait :

En apparence, le statut d’entreprise à mission rencontre un succès d’estime avec une cinquantaine d’entreprises très différentes, d’agences conseils à des sociétés mutuelles, qui l’ont adopté. Ce n’est pas le cas du statut de raison d’être, au bilan beaucoup plus mitigé, car les démarches que l’on connaît expriment des positionnements déclaratifs dans la veine de « la RSE de bonne volonté » qui ne s’accompagnent pas de mécanisme de mesure, de pression et de transparence garantissant de vrais changements d’orientation des modèles.

À la décharge des entreprises qui ont fait preuve d’initiative en la matière, il faut dire que le dispositif légal proposé comporte de considérables faiblesses. L’essentiel du changement juridique porté par la loi réside dans la modification de l’article 1833 du Code civil qui enjoint à toutes les entreprises de « prendre en considération les enjeux sociaux et environnementaux » au côté de l’intérêt social de l’entreprise, dont on n’a pas tiré les implications fondamentales. Les organisations professionnelles concernées ont fait preuve d’un souci défensif, pour limiter la mise en cause conséquente de cette assertion fondamentale, qui acte la nouvelle mission de l’entreprise, à savoir créer de la valeur dans le respect des enjeux sociétaux ; mais ni les juges, ni la puissance publique n’ont eu encore le souci d’accompagner ce cadre, cherchant plutôt à le minimiser, alors même que c’est une innovation majeure : il articule l’économie de marché avec la stratégie nationale de développement durable (ODD) et il crée le socle de ce qu’on appelle désormais « l’économie responsable », consacrée par la nomination pertinente d’une ministre en charge du sujet, qu’on aurait pu ou du appeler aussi « l’économie durable » dans un souci de cohérence politique.

Le texte de loi appelle des transformations de fond dans la gouvernance des entreprises qui devrait se poser des questions à cet effet, sans attendre qu’une jurisprudence fasse le travail pour dire qu’un Conseil d’administration ou une direction générale a mesestimé les enjeux sociaux et environnementaux, définis désormais de façon claire et objective (cf. indicateurs des ODD, incluant l’alignement sur l’Accord de Paris etc.).

L’entreprise dispose de tous les éléments pour établir son niveau de durabilité qui reconnaît cette prise de considération attendue des enjeux communs ; le travail de fond engagé parallèlement en Europe afin de standardiser l’information extra-financière ne pourra qu’encourager les Conseils à débattre et à décider de l’état de leur trajectoire économique au regard de leurs impacts acceptables qui sera la règle en 2025, à n’en pas douter.

Certaines entreprises ont tenu à disposer d’un cadre formel beaucoup plus structuré pour assumer cette responsabilité élargie à la Société, celui de « l’entreprise à mission » ; il constitue une facilité juridique et une aide technique qui a le plus grand intérêt pour accélérer la mutation d’un « capitalisme a-moral » vers « un capitalisme « parties prenantes ». Ce choix implique le vote par les actionnaires, le comité de suivi, l’audit de contrôle etc.. Les actionnaires n’ont pas à craindre pour autant une démission de l’engagement fiduciaire, à leur détriment, car le contrat est explicite, même s’il gagnerait encore à ce que les objectifs de rendement financier soient précisés au regard des objectifs d’amélioration de la création et de la répartition de la valeur globale et de leurs ROI. Ceci afin de ne pas glisser vers « le non profit » : une attention déséquilibrée en faveur de la dimension sociétale de la mission marginaliserait le dispositif, alors que les statuts coopératif, mutualiste ou solidaire sont là pour ça.

Coincé entre le droit général et le cadre précis de « la mission », « la raison d’être » aura du mal à trouver sa place, d’autant que la loi Pacte ne dit rien sur le comment, laissant l’entreprise libre de son engagement, de son inclusion ou non dans les statuts, ce qui en fait un process au mieux pédagogique et au pire de communication ; les parties prenantes ne voient pas les conclusions qu’on en tire sur les conditions nouvelles de production et de répartition de la valeur – objectifs et indicateurs à l’appui- pour exclure ce qui n’est pas « durable » dans l’offre et équilibrer l’allocation des résultats, voire la négocier, s’il existe un mécanisme ad hoc en amont de « l’arbitraire » des conseils. On voit bien qu’une Raison d’Etre bien posée conduit à terme au mécanisme de l’entreprise à mission et que dans le cas contraire l’entreprise ne fait que s’exposer à des critiques et frustrations qui mettent sa stratégie au défi de la cohérence et de la constance d’une gouvernance qui voudrait avancer sans oser le demander à ses actionnaires…

Cette décantation se fera inévitablement dans le temps, au détriment des entreprises « superficielles » et à l’avantage des entreprises authentiques. Le dispositif de Raison d’Etre va devenir un statut intermédiaire, de transition vers « l’entreprise à mission » ; il pousse à la construction d’un droit des sociétés qui recherche le changement profond de la gouvernance actionnariale, comme vient de le proposer la Commission Européenne dans un rapport très critique sur l’engagement insuffisant des gouvernances qui s’abritent derrière des intentions pour répondre aux pressions, rendant leur projet illisible ! Mais rien n’empêche les gouvernances d’accélérer par elles-mêmes sans attendre un règlement européen et éviter les malentendus autour d’une « raison d’être incantatoire » qui mine la crédibilité des initiatives sociétales des entreprises ; dans un monde périlleux, les gouvernances doivent « choisir leur camp » !

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement normes de droit objectifs de l'entreprise Responsabilité sociale des entreprises Valeur actionnariale vs. sociétale

50 years later, Milton Friedman’s shareholder doctrine is dead

Ivan Tchotourian 16 septembre 2020 Ivan Tchotourian

Belle tribune dans Fortune de MM. Colin Mayer, Leo Strine Jr et Jaap Winter au titre clair : « 50 years later, Milton Friedman’s shareholder doctrine is dead » (13 septembre 2020).

Extrait :

Fifty years ago, Milton Friedman in the New York Times magazine proclaimed that the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits. Directors have the duty to do what is in the interests of their masters, the shareholders, to make as much profit as possible. Friedman was hostile to the New Deal and European models of social democracy and urged business to use its muscle to reduce the effectiveness of unions, blunt environmental and consumer protection measures, and defang antitrust law. He sought to reduce consideration of human concerns within the corporate boardroom and legal requirements on business to treat workers, consumers, and society fairly.

Over the last 50 years, Friedman’s views became increasingly influential in the U.S. As a result, the power of the stock market and wealthy elites soared and consideration of the interests of workers, the environment, and consumers declined. Profound economic insecurity and inequality, a slow response to climate change, and undermined public institutions resulted. Using their wealth and power in the pursuit of profits, corporations led the way in loosening the external constraints that protected workers and other stakeholders against overreaching.

Under the dominant Friedman paradigm, corporations were constantly harried by all the mechanisms that shareholders had available—shareholder resolutions, takeovers, and hedge fund activism—to keep them narrowly focused on stockholder returns. And pushed by institutional investors, executive remuneration systems were increasingly focused on total stock returns. By making corporations the playthings of the stock market, it became steadily harder for corporations to operate in an enlightened way that reflected the real interests of their human investors in sustainable growth, fair treatment of workers, and protection of the environment.

Half a century later, it is clear that this narrow, stockholder-centered view of corporations has cost society severely. Well before the COVID-19 pandemic, the single-minded focus of business on profits was criticized for causing the degradation of nature and biodiversity, contributing to global warming, stagnating wages, and exacerbating economic inequality. The result is best exemplified by the drastic shift in gain sharing away from workers toward corporate elites, with stockholders and top management eating more of the economic pie.

Corporate America understood the threat that this way of thinking was having on the social compact and reacted through the 2019 corporate purpose statement of the Business Roundtable, emphasizing responsibility to stakeholders as well as shareholders. But the failure of many of the signatories to protect their stakeholders during the coronavirus pandemic has prompted cynicism about the original intentions of those signing the document, as well as their subsequent actions.

Stockholder advocates are right when then they claim that purpose statements on their own achieve little: Calling for corporate executives who answer to only one powerful constituency—stockholders in the form of highly assertive institutional investors—and have no legal duty to other stakeholders to run their corporations in a way that is fair to all stakeholders is not only ineffectual, it is naive and intellectually incoherent.

What is required is to match commitment to broader responsibility of corporations to society with a power structure that backs it up. That is what has been missing. Corporate law in the U.S. leaves it to directors and managers subject to potent stockholder power to give weight to other stakeholders. In principle, corporations can commit to purposes beyond profit and their stakeholders, but only if their powerful investors allow them to do so. Ultimately, because the law is permissive, it is in fact highly restrictive of corporations acting fairly for all their stakeholders because it hands authority to investors and financial markets for corporate control.

Absent any effective mechanism for encouraging adherence to the Roundtable statement, the system is stacked against those who attempt to do so. There is no requirement on corporations to look after their stakeholders and for the most part they do not, because if they did, they would incur the wrath of their shareholders. That was illustrated all too clearly by the immediate knee-jerk response of the Council of Institutional Investors to the Roundtable declaration last year, which expressed its disapproval by stating that the Roundtable had failed to recognize shareholders as owners as well as providers of capital, and that “accountability to everyone means accountability to no one.”

If the Roundtable is serious about shifting from shareholder primacy to purposeful business, two things need to happen. One is that the promise of the New Deal needs to be renewed, and protections for workers, the environment, and consumers in the U.S. need to be brought closer to the standards set in places like Germany and Scandinavia.

But to do that first thing, a second thing is necessary. Changes within company law itself must occur, so that corporations are better positioned to support the restoration of that framework and govern themselves internally in a manner that respects their workers and society. Changing the power structure within corporate law itself—to require companies to give fair consideration to stakeholders and temper their need to put profit above all other values—will also limit the ability and incentives for companies to weaken regulations that protect workers, consumers, and society more generally.

To make this change, corporate purpose has to be enshrined in the heart of corporate law as an expression of the broader responsibility of corporations to society and the duty of directors to ensure this. Laws already on the books of many states in the U.S. do exactly that by authorizing the public benefit corporation (PBC). A PBC has an obligation to state a public purpose beyond profit, to fulfill that purpose as part of the responsibilities of its directors, and to be accountable for so doing. This model is meaningfully distinct from the constituency statutes in some states that seek to strengthen stakeholder interests, but that stakeholder advocates condemn as ineffectual. PBCs have an affirmative duty to be good corporate citizens and to treat all stakeholders with respect. Such requirements are mandatory and meaningful, while constituency statutes are mushy.

The PBC model is growing in importance and is embraced by many younger entrepreneurs committed to the idea that making money in a way that is fair to everyone is the responsible path forward. But the model’s ultimate success depends on longstanding corporations moving to adopt it.

Even in the wake of the Roundtable’s high-minded statement, that has not yet happened, and for good reason. Although corporations can opt in to become a PBC, there is no obligation on them to do so and they need the support of their shareholders. It is relatively easy for founder-owned companies or companies with a relatively low number of stockholders to adopt PBC forms if their owners are so inclined. It is much tougher to obtain the approval of a dispersed group of institutional investors who are accountable to an even more dispersed group of individual investors. There is a serious coordination problem of achieving reform in existing corporations.

That is why the law needs to change. Instead of being an opt-in alternative to shareholder primacy, the PBC should be the universal standard for societally important corporations, which should be defined as ones with over $1 billion of revenues, as suggested by Sen. Elizabeth Warren. In the U.S., this would be done most effectively by corporations becoming PBCs under state law. The magic of the U.S. system has rested in large part on cooperation between the federal government and states, which provides society with the best blend of national standards and nimble implementation. This approach would build on that.

Corporate shareholders and directors enjoy substantial advantages and protections through U.S. law that are not extended to those who run their own businesses. In return for offering these privileges, society can reasonably expect to benefit, not suffer, from what corporations do. Making responsibility in society a duty in corporate law will reestablish the legitimacy of incorporation.

There are three pillars to this. The first is that corporations must be responsible corporate citizens, treating their workers and other stakeholders fairly, and avoiding externalities, such as carbon emissions, that cause unreasonable or disproportionate harm to others. The second is that corporations should seek to make profit by benefiting others. The third is that they should be able to demonstrate that they fulfill both criteria by measuring and reporting their performances against them.

The PBC model embraces all three elements and puts legal, and thus market, force behind them. Corporate managers, like most of us, take obligatory duties seriously. If they don’t, the PBC model allows for courts to issue orders, such as injunctions, holding corporations to their stakeholder and societal obligations. In addition, the PBC model requires fairness to all stakeholders at all stages of a corporation’s life, even when it is sold. The PBC model shifts power to socially responsible investment and index funds that focus on the long term and cannot gain from unsustainable approaches to growth that harm society.

Our proposal to amend corporate law to ensure responsible corporate citizenship will prompt a predictable outcry from vested interests and traditional academic quarters, claiming that it will be unworkable, devastating for entrepreneurship and innovation, undermine a capitalist system that has been an engine for growth and prosperity, and threaten jobs, pensions, and investment around the world. If putting the purpose of a business at the heart of corporate law does all of that, one might well wonder why we invented the corporation in the first place.

Of course, it will do exactly the opposite. Putting purpose into law will simplify, not complicate, the running of businesses by aligning what the law wants them to do with the reason why they are created. It will be a source of entrepreneurship, innovation, and inspiration to find solutions to problems that individuals, societies, and the natural world face. It will make markets and the capitalist system function better by rewarding positive contributions to well-being and prosperity, not wealth transfers at the expense of others. It will create meaningful, fulfilling jobs, support employees in employment and retirement, and encourage investment in activities that generate wealth for all.

We are calling for the universal adoption of the PBC for large corporations. We do so to save our capitalist system and corporations from the devastating consequences of their current approaches, and for the sake of our children, our societies, and the natural world.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance rémunération Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Rémunération et COVID-19 : étude américaine sur les impacts de la pandémie

Ivan Tchotourian 2 septembre 2020

Dans un article intitulé « The Pandemic and Executive Pay », Aniel Mahabier, Iris Gushi, and Thao Nguyen reviennent sur les conséquences de la COVID-19 en termes de niveaux de rémunération des CA et des hauts-dirigeants. Portant sur les entreprises du Russell 3000, cet article offre une belle synthèse et est très parlante.

Extrait :

Is Reducing Base Salary Enough?

While salary reductions for Executives are greatly appreciated in this difficult time and are meant to show solidarity with employees, the fact is that base salary is only a fraction of the often enormous compensation packages granted to CEO’s and other Executives. Compensation packages predominately consist of cash bonuses and equity awards. Even though 80% of the Russell 3000 companies have disclosed 2019 compensation for Executives, we have not witnessed any companies making adjustments to these figures in light of the crisis, even for companies in hard-hit industries.

Edward Bastian, CEO of Delta Airlines, has agreed to cut 100% of his base salary for 6 months, [1] which equals USD 714,000, but still holds on to his 2019 cash and stock awards of USD 16 million, which were granted earlier in 2020. [2] Another interesting case is MGM Resorts International, where CEO Jim Murren was supposed to stay through 2021 to receive USD 32 million in compensation, including USD 12 million in severance. According to the terms of his termination agreement, he would not receive the compensation package if he left before 2021. [3] However, days after he resigned voluntarily in March, MGM announced that his resignation would be treated as a “termination without good cause”, which would qualify him to receive the full USD 32 million package. [4] In the meantime, 63,000 employees of MGM have been furloughed and will possibly be fired. [5]

Furthermore, activist investors have begun to feel unhappy about some executive pay actions amid the pandemic. CtW Investment Group, an investor of Uber, urged shareholders to reject Uber’s compensation package at the Annual General Meeting since it includes a USD 100 million equity grant to the CEO. [6]

While the ride-hailing company has suffered from a USD 2.9 billion first quarter net loss in 2020 [7] and planned to lay off 6,700 employees [8] (about 30% of its workforce), its CEO Dara Khosrowshahi only took a 100% base salary cut from May until the end of 2020, [9] which totals USD 666,000, and took home a USD 42.4 million pay package for 2019.

The same investor also urged shareholders of McDonald’s to vote against the USD 44 million+ exit package, including USD 700,000 in cash severance, for former CEO Stephen Easterbrook, who was fired last year over violation of company policies due to his relationship with an employee. [10]

The investor’s efforts failed in both instances and the CEO’s took home millions of dollars while their companies are struggling.

Since the COVID-19 outbreak, a number of public companies have gone bankrupt. Nevertheless, large sums of compensation were paid out to their Executives. Retailer J. C. Penney paid almost USD 10 million in bonuses to top executives [11] and oil company Whiting Petroleum issued USD 14.6 million in bonuses for its C-suite, [12] just days before both companies filed for bankruptcy.

Another school of thought is that the practice of issuers deferring executive salary cuts into RSUs will give rise to huge payouts in the future when the market eventually recovers and share value increases. This means that Executives who deferred their base salary have made a sacrifice that ultimately will benefit them, defeating the purpose of pay cuts.

Although the economic impacts of the pandemic on businesses are still on-going, the number of pay cuts announced has slowed since the end of May. As the effects continue to unfold over the next months, we expect companies to continue to re-evaluate their executive compensation policies. COVID-19 has changed daily lives, business operations, and the economy. Even though we will only know the full extent of impact in the second half of 2020, COVID-19 will certainly change executive pay and corporate governance practices in the future.

À la prochaine…