Normes d’encadrement | Page 9

Base documentaire Gouvernance loi et réglementation Normes d'encadrement normes de droit normes de marché

Billet du professeur Stéphane Rousseau : jalon de la gouvernance

Ivan Tchotourian 21 mars 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

Merci à Stéphane Rousseau qui publie sur son blogue Gouvernance et droit des marchés financiers un billet bien intéressant (à son habitude !) : « Les grands jalons de la gouvernance d’entreprise au Canada ».

Stéphane Rousseau y aborde les grands jalons de la gouvernance au Canada.

À la prochaine…

devoir de vigilance Gouvernance normes de droit Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Bilan du devoir de vigilance

Ivan Tchotourian 21 mars 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

Récemment, l’Assemblée nationale française a publié un rapport d’information sur l’évaluation de la loi du 27 mars 2017 relative au devoir de vigilance des sociétés mères et des entreprises donneuses d’ordre.

Pour accéder au rapport : cliquez ici

Les points à améliorer sont les suivants :

I. UN PÉRIMÈTRE LARGE POUR PRÉVENIR LES ATTEINTES AUX DROITS SOCIAUX ET ENVIRONNEMENTAUX TOUT AU LONG DE LA CHAÎNE DE VALEUR

A. UN PÉRIMÈTRE PERTINENT POUR COUVRIR L’ENSEMBLE DES ATTEINTES

1. Malgré des difficultés initiales pour cerner le champ du devoir de vigilance…

a. Une loi supposément « floue »

b. Une notion d’atteintes graves qui renvoie indirectement aux principes directeurs de l’ONU

2. …le périmètre large de cette obligation est essentiel pour prévenir efficacement les risques

B. UN DEVOIR DE VIGILANCE QUI DOIT COUVRIR L’ENSEMBLE DE LA CHAÎNE DE VALEUR DE LA SOCIÉTÉ-MÈRE

1. Une notion de « relation commerciale établie » volontairement large

2. Une interprétation jurisprudentielle potentiellement différente de la relation commerciale établie

C. UNE ASSOCIATION DES PARTIES PRENANTES À L’ÉLABORATION DU PLAN QUI DEMEURE INSUFFISANTE

1. Une association des parties prenantes laissée à la libre appréciation des entreprises

2. Une association des parties prenantes qui s’apparente, lorsqu’elle existe, à une simple information

II. UN CHAMP D’APPLICATION AUX ENTREPRISES AYANT LE PLUS DE SALARIÉS, ÉCARTANT CERTAINS ACTEURS MAJEURS

A. UNE EXCLUSION DE CERTAINES FORMES DE SOCIÉTÉS QUI RESTREINT L’APPLICATION DE LA LOI

1. La nécessité d’appliquer la loi aux sociétés par actions simplifiées

2. Vers une application de la loi à toutes les formes sociales

a. Une inclusion très souhaitable des SARL

b. Vers une intégration des SNC dans le champ du devoir de vigilance

c. Vers une intégration des coopératives agricoles

B. UN CRITÈRE LIÉ AU NOMBRE DE SALARIÉS TROP RESTRICTIF

1. Un assujettissement lié au seul critère du nombre de salariés qui pose plusieurs difficultés

a. Des seuils qui empêchent de connaître précisément la liste des entreprises assujetties

b. Des seuils trop élevés qui excluent de nombreuses entreprises dont l’activité présente des risques

2. L’introduction d’autres critères, alternatifs, permettrait d’élargir le champ du devoir de vigilance

III. LA DESCRIPTION DU CONTENU DU PLAN DE VIGILANCE DANS LA LOI NE PERMET PAS DE REMÉDIER À LA GRANDE HÉTÉROGÉNÉITÉ DES PRATIQUES

A. LA CARTOGRAPHIE DES RISQUES : DES RÉSULTATS CONTRASTÉS POUR UN EXERCICE POURTANT ESSENTIEL

1. Le recours au « droit souple » pour mieux appréhender cette obligation

2. L’absence d’harmonisation des cartographies

3. L’assistance des services économiques régionaux pour remédier aux asymétries d’information

B. DES INTERROGATIONS QUANT AU PÉRIMÈTRE DE L’OBLIGATION D’ÉVALUATION DES RISQUES

1. Des obligations généralement étendues aux seuls sous-traitants et fournisseurs de premier rang

2. Des rapports de force parfois défavorables à la société mère ou donneuse d’ordre

3. Une évaluation qui a des conséquences sur les petites et moyennes entreprises

C. DES ACTIONS (PEU) ADAPTÉES D’ATTÉNUATION DES RISQUES OU DE PRÉVENTION DES ATTEINTES GRAVES

1. Une exigence déclinée en droit international

2. Une obligation qui semble insuffisamment et irrégulièrement appliquée

D. L’INSTAURATION D’UNE PROCÉDURE DE SIGNALEMENT EN PRINCIPE DISTINCTE DU DISPOSITIF GÉNÉRAL D’ALERTE DE LA LOI SAPIN II

1. L’adresse e-mail, un moyen d’alerte utile mais insuffisant

2. La confusion avec le dispositif d’alerte prévu au titre de la loi « Sapin II »

E. LE DISPOSITIF DE SUIVI DES MESURES MISES EN ŒUVRE ET D’ÉVALUATION DE LEUR EFFICACITÉ : UNE OBLIGATION DONT LE RESPECT DÉCOULE DE TOUTES LES AUTRES

IV. LA NÉCESSITÉ DE METTRE EN PLACE UNE AUTORITÉ ADMINISTRATIVE DE CONTRÔLE, SANS PRÉJUDICE DE RECOURS JUDICIAIRES

A. UN RESPECT DE LA LOI QUI REPOSE AUJOURD’HUI SUR DEUX PROCÉDURES JURIDICTIONNELLES

1. Une absence de décision de justice qui complique la mise en œuvre de la loi

a. Quatre actions en injonction

b. Une action en responsabilité

2. L’absence de sanctions du fait de la décision du Conseil constitutionnel

B. UNE AUTORITÉ ADMINISTRATIVE DE CONTRÔLE DOIT ÊTRE MISE EN PLACE SOUS CERTAINES CONDITIONS, SANS PRÉJUDICE DES RECOURS CONTENTIEUX

1. Un manque de suivi de la mise en œuvre de la loi

2. La nécessité d’accompagner la mise en œuvre du devoir de vigilance

3. Vers un contrôle administratif du respect des obligations légales

a. Des entreprises frileuses à l’instauration d’un contrôle administratif

b. Des craintes soulevées par des associations et des universitaires

c. Vers une mission de surveillance administrative, sans préjudice de recours judiciaires

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement Structures juridiques

Cahier sur la raison d’être

Ivan Tchotourian 21 mars 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

À l’été 2020, Entrepreneurs & dirigeants chrétiens (EDC) a publié un cahier à lire : « Cahier des EDC : Raison d’être de l’entreprise ».

Résumé

Si la responsabilité sociale de l’entreprise n’est pas chose nouvelle pour les chrétiens, la notion de « raison d’être » de l’entreprise leur ouvre une nouvelle occasion de s’interroger sur le sens à lui donner et l’opportunité́ de réfléchir sur les missions des entreprises, au regard non seulement de la conduite des affaires, mais aussi de l’enseignement de la Pensée Sociale Chrétienne.

Dans la période difficile que traversent de nombreuses entreprises, cette notion de « raison d’être » rappelle aux entrepreneurs tentés de se replier sur leurs urgences et leurs chiffres qu’ils peuvent puiser de l’espérance dans le sens de leur travail.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance mission et composition du conseil d'administration Normes d'encadrement

Les CA à l’heure de la cybersécurité

Ivan Tchotourian 21 mars 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

Intéressant article de Finance et investissement qui interview Anne-Marie Croteau, Doyenne de l’École de gestion John-Molson de l’Université Concordia suite à un récent webinaire des Jeunes administrateurs de l’Institut sur la gouvernance d’organisations privées et publiques (IGOPP) sur l’enjeu de la gouvernance à l’ère de la cybersécurité et de la transition numérique : J.-F. Barbe, « Les CA à l’heure de la cybersécurité », Finance et investissement, 5 janvier 2022

Voici quelques extraits :

« Dans les CA, la techno est trop souvent vue comme étant un coût. On oublie que des situations problématiques en cybersécurité ou en TI peuvent faire flancher l’organisation »

Selon elle, les CA doivent intégrer des « gens d’expérience » en technologies de l’information qui auront la capacité d’éduquer et d’informer l’équipe de direction incluant les responsables des technologies de l’information (CIO). Des connaissances de pointe pourraient alors être mieux diffusées à l’interne

« Les membres de CA ayant les connaissances suffisantes ne devraient pas hésiter à rencontrer personnellement les responsables des technologies de l’information afin de les aider à remplir leurs rôles »

Celle qui est aussi professeure titulaire en gestion des technologies de l’information à l’Université Concordia ajoute que les CA ont intérêt à entendre des points de vue d’experts situés hors de l’organisation. Dans cet esprit, elle suggère de faire appel à des spécialistes de la veille technologique, à des consultants en TI et dans le cas des grandes entreprises, aux Gartner de ce monde

« Il ne faut pas craindre d’être accompagnés, notamment dans l’élaboration de diagnostics touchant la protection des données. Des consultants peuvent évaluer la maturité de l’organisation concernant les TI et la cybersécurité, faisant en sorte que leurs recommandations remonteront au CA »

À la prochaine…

Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Gouvernance normes de droit Responsabilité sociale des entreprises

Changement climatique : proposition de la SEC

Ivan Tchotourian 21 mars 2022 Ivan Tchotourian

L’autorité boursière étatsunienne vient de publier sa proposition en mati`ère de transparence du risque climatique : « The Enhancement and Standardization of Climate-Related Disclosures for Investors ».

Résumé

The Securities and Exchange Commission (“Commission”) is proposing for public comment amendments to its rules under the Securities Act of 1933 (“Securities Act”) and Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (“Exchange Act”) that would require registrants to provide certain climate-related information in their registration statements and annual reports. The proposed rules would require information about a registrant’s climate-related risks that are reasonably likely to have a material impact on its business, results of operations, or financial condition. The required information about climate-related risks would also include disclosure of a registrant’s greenhouse gas emissions, which have become a commonly used metric to assess a registrant’s exposure to such risks. In addition, under the proposed rules, certain climate-related financial metrics would be required in a registrant’s audited financial statements.

À la prochaine…

Gouvernance Normes d'encadrement objectifs de l'entreprise

L’intérêt de l’entreprise en Allemagne : aperçu historique

Ivan Tchotourian 12 mai 2021 Ivan Tchotourian

Merci à la professeure Anne-Christin Mittwoch de nous offrir une très belle synthèse sur la notion d’intérêt social en droit allemand pour montrer que la notion de raison d’être doit être comprise en lien avec elle. Un billet à lire de toute urgence !

Extrait :

Lessons learnt from legal history: the company’s role in society as a whole

The company interest has a tradition of almost a hundred years, its roots dating even further back. The intersection between private and public interests has its origin in ancient Roman law that had been absorbed by German legal scholars since the 12th century. This tradition has made it difficult to align private and public interests explicitly within the definition of the corporate purpose – until today, public and private law are considered separate. Thus, the early phase of German stock corporation regulation in the 19th century was characterized by a sharp dichotomy of public and private interests (rather than shareholder and stakeholder interests). They seemed so incompatible with each other that the German octroi and concession system sought to interweave them in regulatory terms in order to provide protection for society against the unbridled pursuit of private interests of corporate managers and to deal with the threat this posed to the public good. As a result, it was not possible to incorporate in Germany between 1794 and 1843 if not for the purpose of the common or public good.

The common benefit as a condition for incorporation

This strict precondition was abandoned in 1870, but in the 20th century, the discourse on the common good in company law gained ground again with the debate on the concept of the ‘company per se’. This discussion was initiated by Rathenau’s writings and aimed at a practical independence of the company from its governing bodies and their individual interests. Due to their considerable macroeconomic importance, Rathenau considered stock corporations no longer the sole objects of the private interests of shareholders but demanded that they should be detached from the purely private sector and linked to the interests of the state and civil society. Consequentially, the Stock Corporation Act of 1937 stipulated: ‘The Management Board shall, under its own responsibility, manage the company in such a way as […] the common benefit of the people and the state demand’.

The 1965 amendment to the Stock Corporation Act erased this statement from the wording of the law, because of its Nazi connotations and because it was deemed unnecessary to spell out the obvious. The continued validity of the common benefit as an unwritten principle of stock corporation law has since then been discussed and the development of codetermination in the 1970s intensified this discussion.

Where is the concept of company interest today?

In the following decades, various understandings of the interest of the company were put forward by academics and shaped this concept that until today is considered the major guideline for board members’ actions. Since the 1990s, the debate has opened up to the Anglo-American shareholder-stakeholder dichotomy and its influences can be seen in today’s foreword of the GCGC. However, binding standards of conduct for corporate bodies as well as for an associated liability were not developed. Does this render the concept of the company interest useless? No. It offers a framework, an overarching normative idea, in which different legal obligations for board members can be placed and interpreted. And its dynamic offers flexibility: it constantly poses the questions of the ‘right’ relationship between company and society and between public regulation and private interests. But currently, flexibility is accompanied by legal uncertainty.

Towards a better framework for the corporate purpose?

Without an explicit definition, the concept of the company interest seems to be at a crossroads. Thus, a legal clarification of its relevance is much needed. This clarification should connect to its historical core: the relation between public and private interests that have to be continuously balanced within corporate decision-making. And the responsibility of the company for the common good as its background. Yet a conclusive definition of its scope will not be possible: History has shown that none of the above-mentioned interest groups dominates over another on an abstract level. And what is in the company interest depends also on the object and the articles of association of the respective enterprise together with the individual situation. Nevertheless, the law can and should make explicitly clear that corporate boards are committed to the company interest. This clarification is not only needed in order to reject the shareholder-stakeholder dichotomy. It can also serve as a reference point for further obligations of the board to foster corporate sustainability. Because ultimately, it is in the enterprise’s best interests, that boards ensure a sustainable value creation within the planetary boundaries.

À la prochaine…

actualités internationales Divulgation divulgation extra-financière Gouvernance normes de droit

Les adieux au reporting extra-financier… vraiment ?

Ivan Tchotourian 29 avril 2021 Ivan Tchotourian

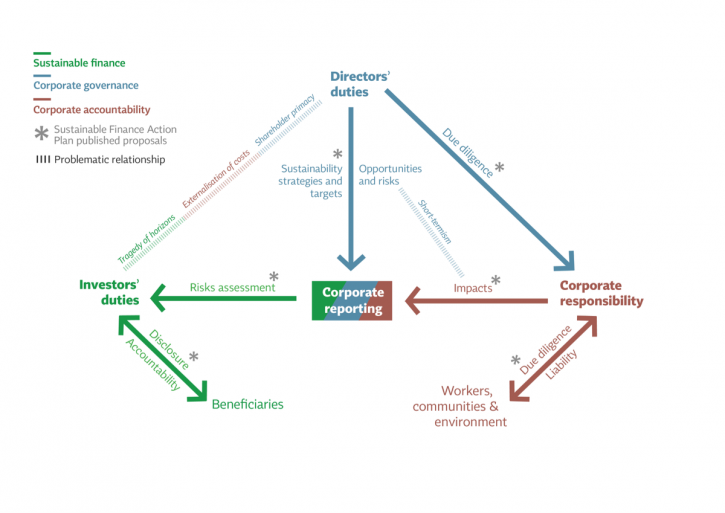

Blogging for sustainability offre un beau billet sur la construction européenne du reporting extra-financier : « Goodbye, non-financial reporting! A first look at the EU proposal for corporate sustainability reporting » (David Monciardini et Jukka Mähönen, 26 April 2021). Les auteurs soulignent la dernière position de l’Union européenne (celle du 21 avril 2021 qui modifie le cadre réglementaire du reporting extra-financier) et explique pourquoi celle-ci est pertinente. Du mieux certes, mais encore des critiques !

Extrait :

A breakthrough in the long struggle for corporate accountability?

Compared to the NFRD, the new proposal contains several positive developments.

First, the concept of ‘non-financial reporting’, a misnomer that was widely criticised as obscure, meaningless or even misleading, has been abandoned. Finally we can talk about mandatory sustainability reporting, as it should be.

Second, the Commission is introducing sustainability reporting standards, as a common European framework to ensure comparable information. This is a major breakthrough compared to the NFRD that took a generic and principle-based approach. The proposal requires to develop both generic and sector specific mandatory sustainability reporting standards. However, the devil is in the details. The Commission foresees that the development of the new corporate sustainability standards will be undertaken by the European Financial Reporting Advisory Group (EFRAG), a private organisation dominated by the large accounting firms and industry associations. As we discuss below, the most important issue is to prevent the risks of regulatory capture and privatization of EU norms. What is a step forward, though, is the companies’ duty to report on plans to ensure the compatibility of their business models and strategies with the transition towards a zero-emissions economy in line with the Paris Agreement.

Third, the scope of the proposed CSRD is extended to include ‘all large companies’, not only ‘public interest entities’ (listed companies, banks, and insurance companies). According to the Commission, companies covered by the rules would more than triple from 11,000 to around 49,000. However, only listed small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are included in the proposal. This is a major flaw in the proposal as the negative social and environmental impacts of some SMEs’ activities can be very substantial. Large subsidiaries are thereby excluded from the scope, which also is a major weakness. Besides, instead of scaling the general standards to the complexity and size of all undertakings, the Commission proposes a two-tier regime, running the risk of creating a ‘double standard’ that is less stringent for SMEs.

Fourth, of the most welcomed proposals, however, is strengthening a ‘double materiality’ principle for standards (making it ‘enshrined’, according to the Commission), to cover not only just the risks of unsustainability to companies themselves but also the impacts of companies on society and the environment. Similarly, it is positive that the Commission maintains a multi-stakeholder approach, whereas some of the international initiatives in place privilege the information needs of capital providers over other stakeholders (e.g. IIRC; CDP; and more recently the IFRS).

Fifth, a step forward is the compulsory digitalisation of corporate disclosure whereby information is ‘tagged’ according to a categorisation system that will facilitate a wider access to data.

Finally, the proposal introduces for the first time a general EU-wide audit requirement for reported sustainability information, to ensure it is accurate and reliable. However, the proposal is watered down by the introduction of a ‘limited’ assurance requirement instead of a ‘reasonable’ assurance requirement set to full audit. According to the Commission, full audit would require specific sustainability assurance standards they have not yet planned for. The Commission proposes also that the Member States allow firms other than auditors of financial information to assure sustainability information, without standardised assurance processes. Instead, the Commission could have follow on the successful experience of environmental audit schemes, such as EMAS, that employ specifically trained verifiers.

No time for another corporate reporting façade

As others have pointed out, the proposal is a long-overdue step in the right direction. Yet, the draft also has shortcomings, which will need to be remedied if genuine progress is to be made.

In terms of standard-setting governance, the draft directive specifies that standards should be developed through a multi-stakeholder process. However, we believe that such a process requires more than symbolic trade union and civil society involvement. EFRAG shall have its own dedicated budget and staff so to ensure adequate capacity to conduct independent research. Similarly, given the differences between sustainability and financial reporting standards, EFRAG shall permanently incorporate a balanced representation of trade unions, investors, civil society and companies and their organisations, in line with a multi-stakeholder approach.

The proposal is ambiguous in relation to the role of private market-driven initiatives and interest groups. It is crucial that the standards are aligned to the sustainability principles that are written in the EU Treaties and informed by a comprehensive science-based understanding of sustainability. The announcement in January 2020 of the development of EU sustainability reporting standards has been followed by the sudden move by international accounting body the IFRS Foundation to create a global standard setting structure, focusing only on financially material climate-related disclosures. In the months to come, we can expect enormous pressure on EU policy-makers to adopt this privatised and narrower approach, widely criticised by the academic community.

Furthermore, the proposal still represents silo thinking, separating sustainability disclosure from the need to review and reform financial accounting rules (that remain untouched). It still emphasises transparency over governance. Albeit it includes a requirement for companies to report on sustainability due diligence and actual and potential adverse impacts connected with the company’s value chain, it lacks policy coherence. The proposal’s link with DG Justice upcoming legislation on the boards’ sustainability due diligence duties later this year is still tenuous.

After decades of struggles for mandatory high-quality corporate sustainability disclosure, we cannot afford another corporate reporting façade. It is time for real progress towards corporate accountability.

À la prochaine…